Table of Contents

Why Read this Guide?

This guide shows how cybersecurity professionals can get up and running quickly with AI tools to:

- augment your skills and amplify your impact

- reduce your toil

Large Language Models (hosted and open source), and BERT-based language models tools will be covered e.g.

- NotebookLM

- Prompts and Prompt Techniques applied to Cybersecurity

- BERTopic

- Embeddings for CyberSecurity

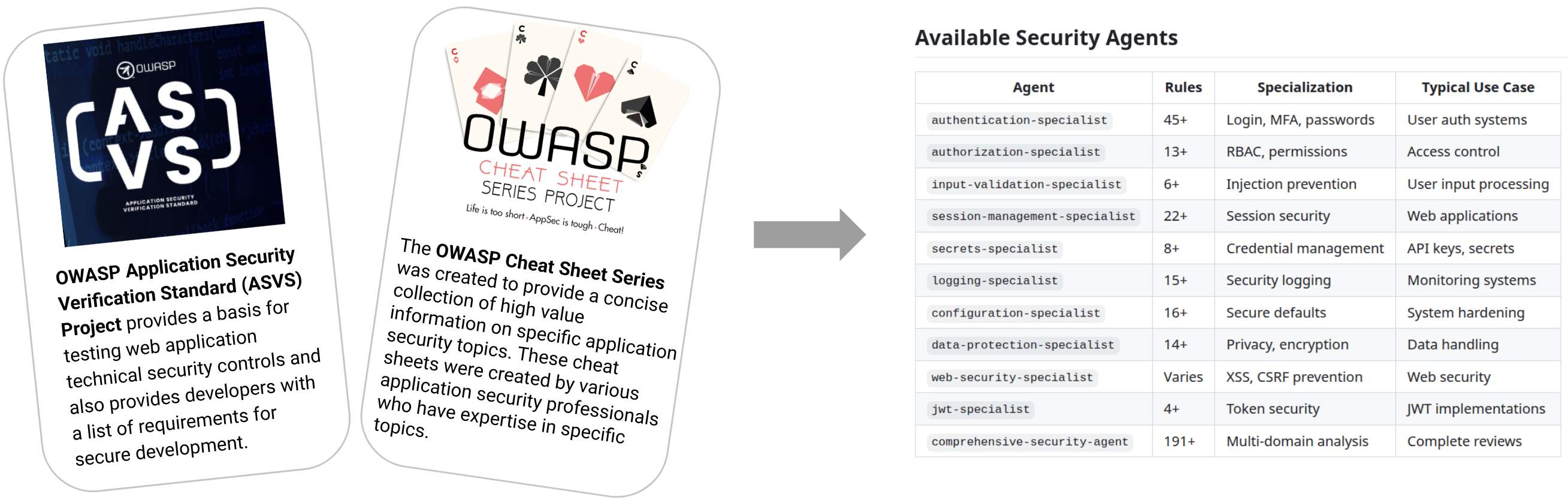

- AI Agents for orchestrated workflows

Risk Based Prioritization Guide

Check out another guide I co-wrote with various thought leaders in vulnerability management https://riskbasedprioritization.github.io/

The Risk Based Prioritization described in this guide significantly reduces the

- cost of vulnerability management

- risk by reducing the time adversaries have access to vulnerable systems they are trying to exploit.

Introduction ↵

Preface¶

Language Models are powerful tools that can be applied to CyberSecurity.

I enjoy learning about, playing with, and applying these tools to better solve problems:

- I wrote this guide for me, to organize my thoughts and my play time as I play with, and apply, Language Models.

- I've found by putting something out there, you get something back.

- It's the guide I wish existed already.

This approach worked well for the Risk-Based Prioritization guide...

You may find it useful.

Introduction¶

About this Guide

This guide is in an initial early access state currently and is written to organize my play time as I play with, and apply, these tools.

The content is about solving real problems e.g. how to

- view the main topics in a set of documents

- validate assigned CWEs, and suggest CWEs to assign

- chat with large documents

- extract configuration parameters from user manuals.

These examples were driven by a user need.

While the examples focus on specific areas, they can be applied in general to many areas.

After reading this guide you should be able to

- Apply Language Models to augment and amplify your skills.

- Understand the types of problems that suit Language Models, and those that don't

Overview¶

Intended Audience¶

The intended audience is people wanting to go beyond the hype and basics of Large Language Models.

No prior knowledge is assumed to read the guide - it provides just enough information to understand the advanced topics covered.

A basic knowledge of Jupyter Python is required to run the code (with the data provided or on your data).

How to Use This Guide¶

How to Contribute to This Guide¶

You can contribute content or suggest changes:

Writing Style¶

The "writing style" in this guide is succinct, and leads with an opinion, with data and code to back it up i.e. data analysis plots (with source code where possible) and observations and takeaways that you can assess - and apply to your data and environment. This allows the reader to assess the opinion and the code/data and rationale behind it.

Different, and especially opposite, opinions with the data to back them up, are especially welcome! - and will help shape this guide.

Quote

If we have data, let’s look at data. If all we have are opinions, let’s go with mine.

Notes¶

Notes

- This guide is not affiliated with any Tool/Company/Vendor/Standard/Forum/Data source.

- Mention of a vendor in this guide is not a recommendation or endorsement of that vendor.

- This guide is a living document i.e. it will change and grow over time - with your input.

This guide is not about which tool is better than the other

"Don't fall in love with models: they're expendable. Fall in love with data!"

Julien Simon, Chief Evangelist, Hugging Face

Warning

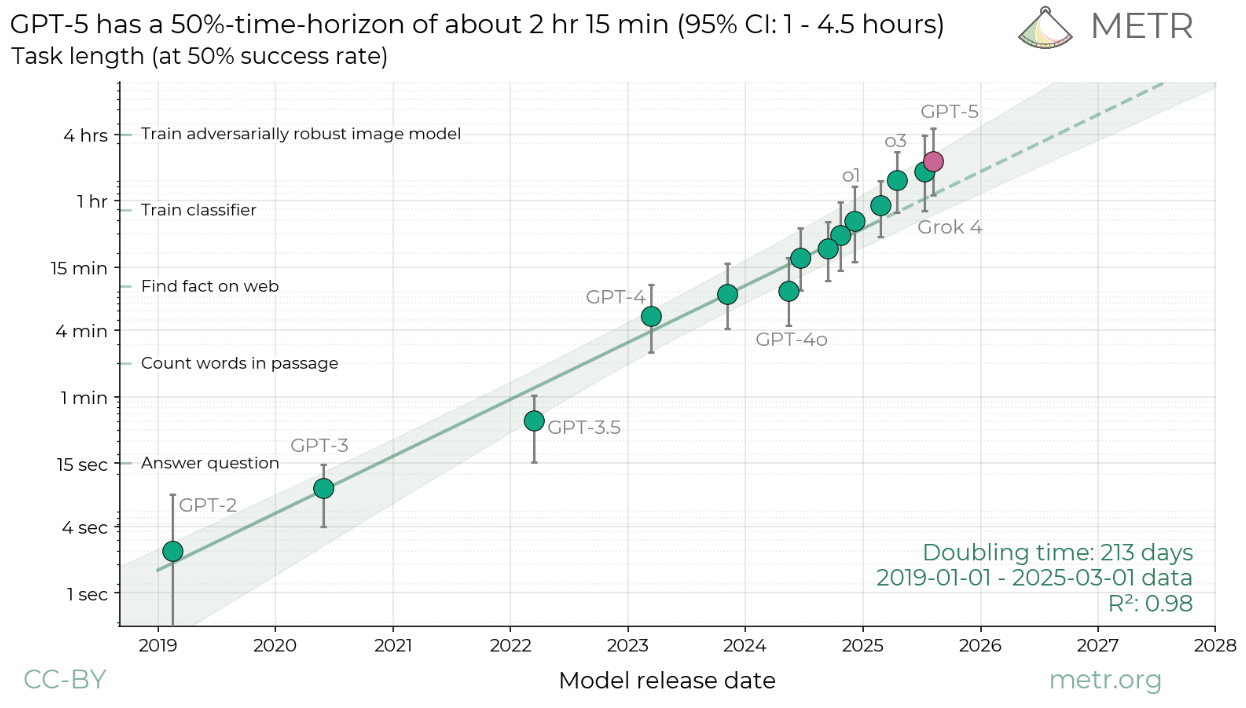

This space is rapidly evolving so the content in this guide may become no longer current or accurate.

Warning

You are responsible for your data and where it goes.

If you don't understand where your data goes, and what happens to it for a given model or tool, then find out before you use private or personal data.

To evaluate models and tools, you can start with public data.

Model Types¶

Overview

This section gives an overview of different model types.

Introduction¶

Different types of text models are designed with varying architectures, training data, and optimization goals, leading to distinct capabilities and best-fit use cases.

While many models focus primarily on text, an increasing number are becoming multimodal, capable of processing and generating information across different types of data, such as text, images, audio, and even video.

Today, these different types of models are generally accessed by selecting the specific model or API endpoint provided by developers (versus the user accessing the same interface that figures out the best type of model).

Deep Research¶

Models in this category are typically designed for in-depth information retrieval, synthesis, and report generation from vast amounts of data, often involving Browse and analyzing multiple sources. They aim to provide comprehensive and well-supported answers to complex queries.

Key Insights:

- Extensive Information Gathering: Excel at searching and processing information from large and diverse datasets, including the web or private document repositories.

- Synthesis and Structuring: Capable of synthesizing information from various sources into coherent and structured reports or summaries.

- Handling Complexity: Designed to tackle complex, multi-faceted research questions that require connecting information across different domains.

- Citation and Verification: Often include features for citing sources, allowing users to verify the information presented.

Use Cases:

- Generating detailed reports on niche or complex topics.

- Performing market research by analyzing industry trends and competitor information.

- Assisting academics and researchers in literature reviews and synthesizing findings.

- Providing comprehensive answers to complex legal, medical, or scientific questions.

- Analyzing large volumes of internal documents to extract insights.

Examples: Perplexity Deep Research, ChatGPT Deep Research, Gemini Deep Research, HuggingFace Open Deep Research, Claude 3 Opus

Reasoning¶

Reasoning-focused models are optimized to perform complex logical deductions, solve problems requiring multiple steps, and understand intricate relationships between concepts. They are built to "think" through problems rather than just retrieving information or generating text based on patterns.

Key Insights:

- Logical Deduction: Strong capabilities in applying logical rules and deriving conclusions from given premises.

- Multi-Step Problem Solving: Can break down complex problems into smaller, manageable steps and follow a chain of thought to reach a solution.

- Mathematical and Scientific Reasoning: Often perform well on mathematical problems, coding challenges, and scientific inquiries that require step-by-step analysis.

- Reduced Hallucination in Complex Tasks: While still a challenge for all LLMs, models focused on reasoning aim to reduce the likelihood of generating false or inconsistent information in complex scenarios by showing their work or using techniques like self-correction.

Use Cases:

- Solving complex mathematical equations or proofs.

- Debugging code and suggesting logical fixes.

- Analyzing data and drawing reasoned conclusions.

- Assisting in strategic planning by evaluating scenarios and predicting outcomes.

- Providing step-by-step explanations for complex concepts or solutions.

- Excelling at benchmarks requiring logical inference and problem-solving.

Examples: DeepSeek-R1, OpenAI’s GPT-4, Google’s Gemini Ultra, Anthropic’s Claude 3 Sonnet, Meta’s Llama 3

General Purpose¶

General-purpose LLMs are designed to be versatile and handle a wide array of natural language tasks. They are trained on broad datasets to provide a good balance of capabilities across different domains without being specifically optimized for one.

Key Insights:

- Versatility: Capable of performing a wide range of tasks, including text generation, summarization, translation, question answering, and creative writing.

- Broad Knowledge: Possess a vast amount of general knowledge from their diverse training data.

- Adaptability: Can often adapt to different styles and formats based on the prompt.

- Accessibility: Typically the most widely available and accessible models for everyday use.

Use Cases:

- Drafting emails, articles, and other written content.

- Summarizing documents or long texts.

- Translating text between languages.

- Answering general knowledge questions.

- Brainstorming ideas and assisting in creative writing.

- Powering chatbots and virtual assistants for a variety of inquiries.

Examples: GPT-4 Turbo, Gemini Pro, Claude 3 Haiku, Mistral Large, Cohere Command R+

Code¶

Code-focused models are specifically trained on large datasets of code from various programming languages and sources. They are designed to understand, generate, and assist with programming tasks.

Key Insights:

- Code Generation: Can generate code snippets, functions, or even entire programs based on natural language descriptions or prompts.

- Code Completion: Provide intelligent suggestions for completing code as developers type.

- Code Explanation and Documentation: Can explain how code works and generate documentation.

- Debugging and Error Detection: Assist in identifying potential errors and suggesting fixes in code.

- Code Translation: Translate code between different programming languages.

- Support for Multiple Languages: Trained on a wide variety of programming languages.

Use Cases:

- Speeding up software development by generating boilerplate code.

- Assisting developers in learning new programming languages or frameworks.

- Automating repetitive coding tasks.

- Improving code quality through suggestions and error detection.

- Generating test cases for software.

- Helping non-programmers understand or modify code.

Examples: CodeLlama (Meta), StarCoder (ServiceNow), Codex (OpenAI), DeepSeek Coder, Google’s Codey

Tip

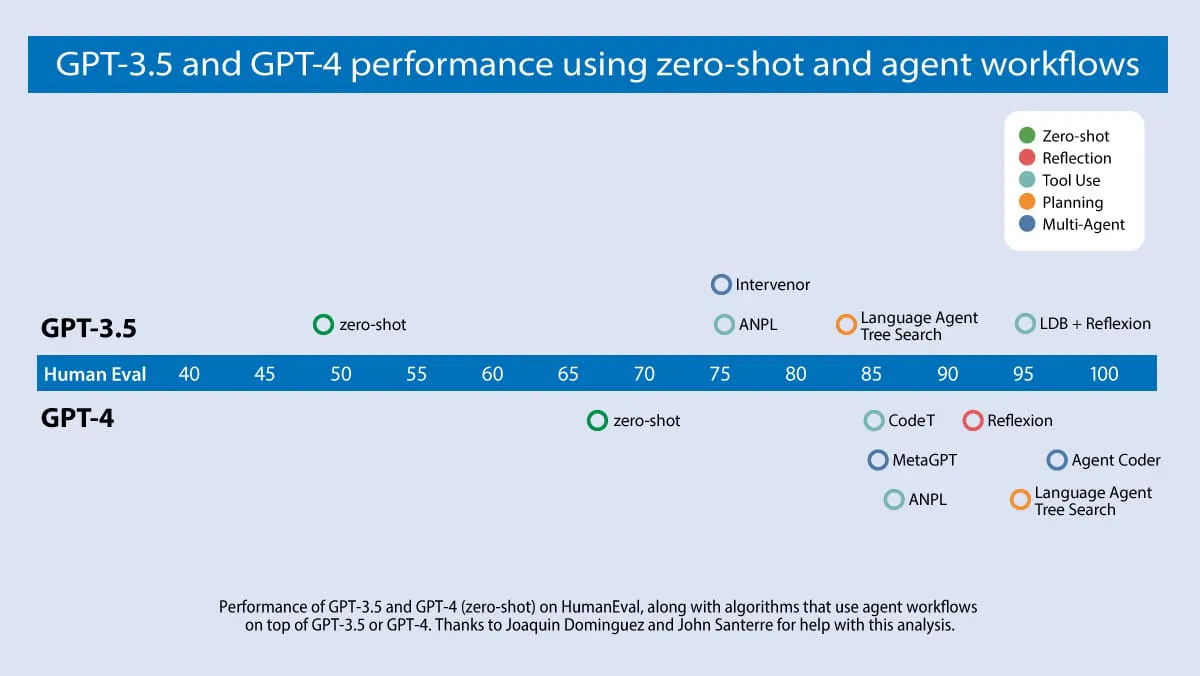

This blog gives a good overview of different models' capabilities for code and echoes my experience.

Tip

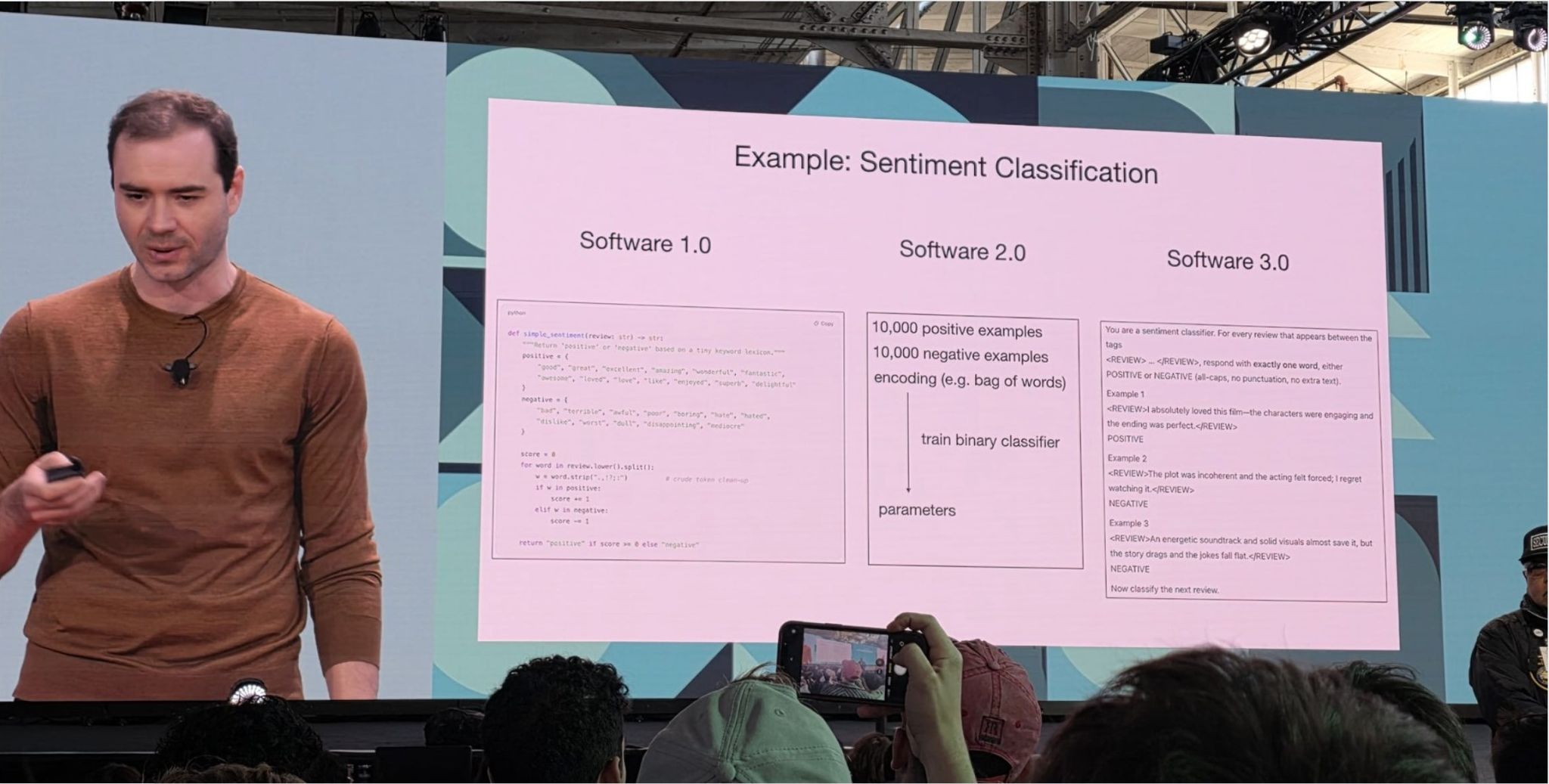

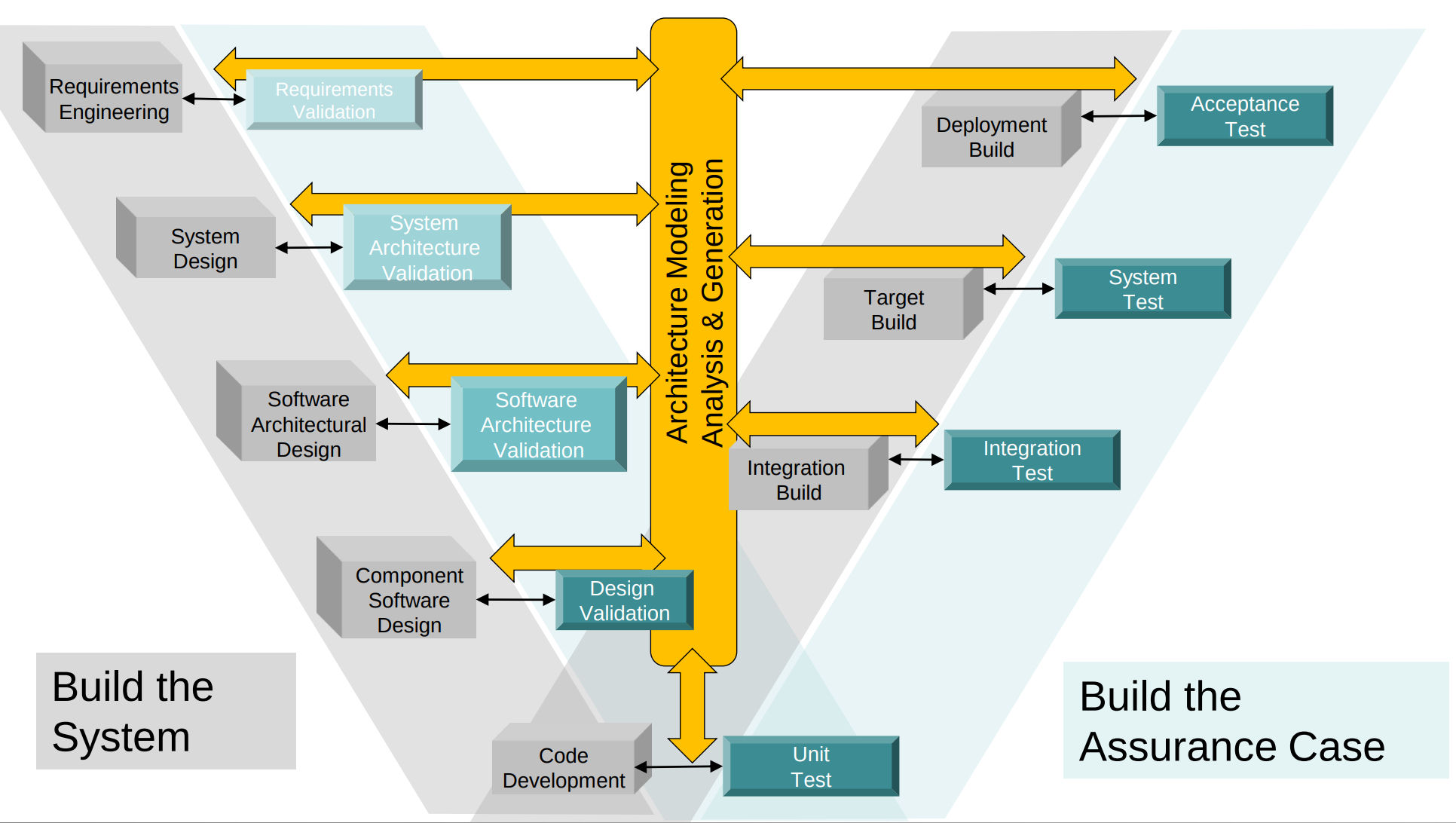

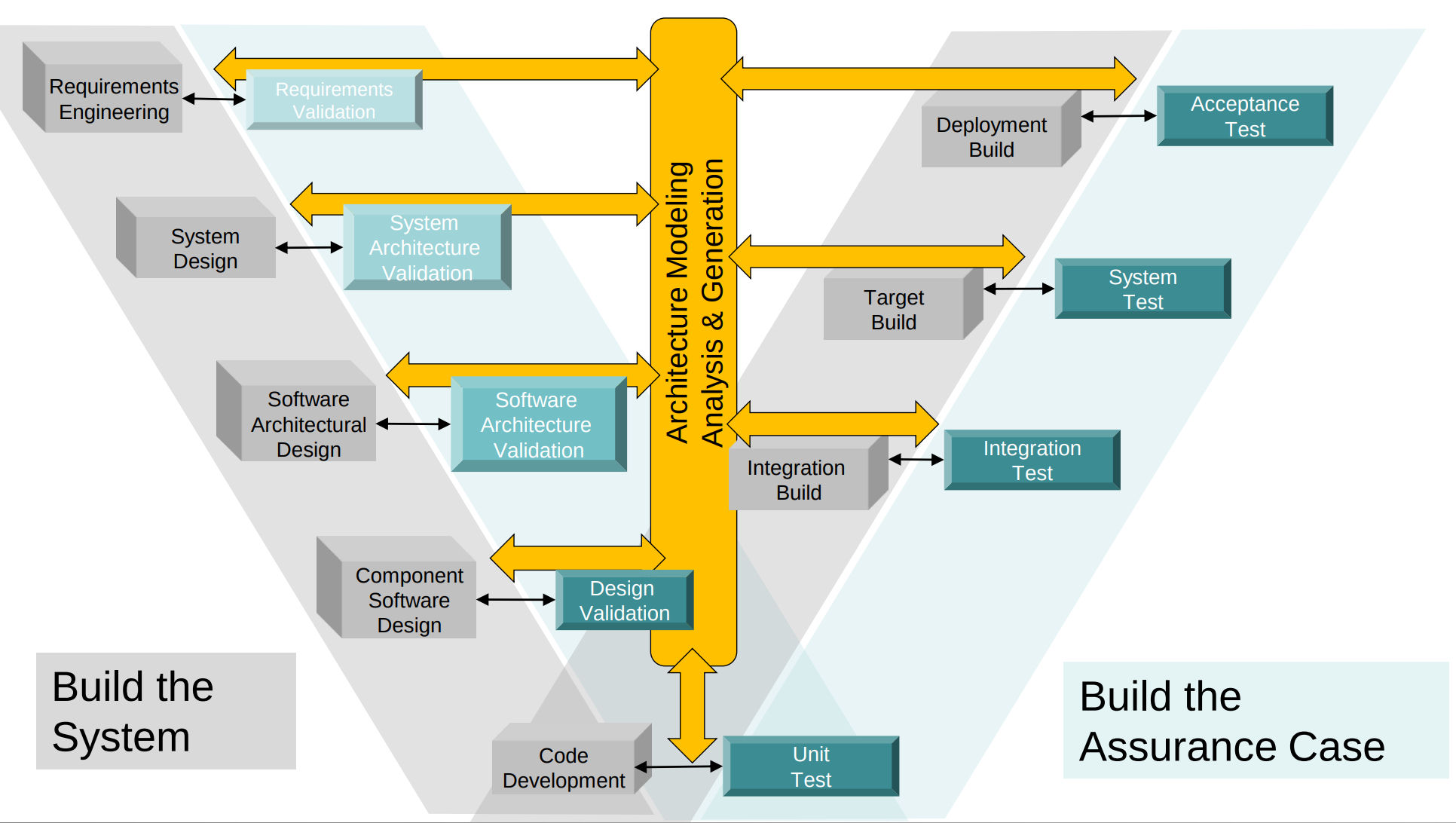

Code Generation is a small part of Software Engineering.

Different model types are suitable for different Software Engineering Artifacts

LLMs for CyberSecurity¶

LLMs for CyberSecurity Users and Use Cases¶

Image from Generative AI and Large Language Models for Cyber Security: All Insights You Need.

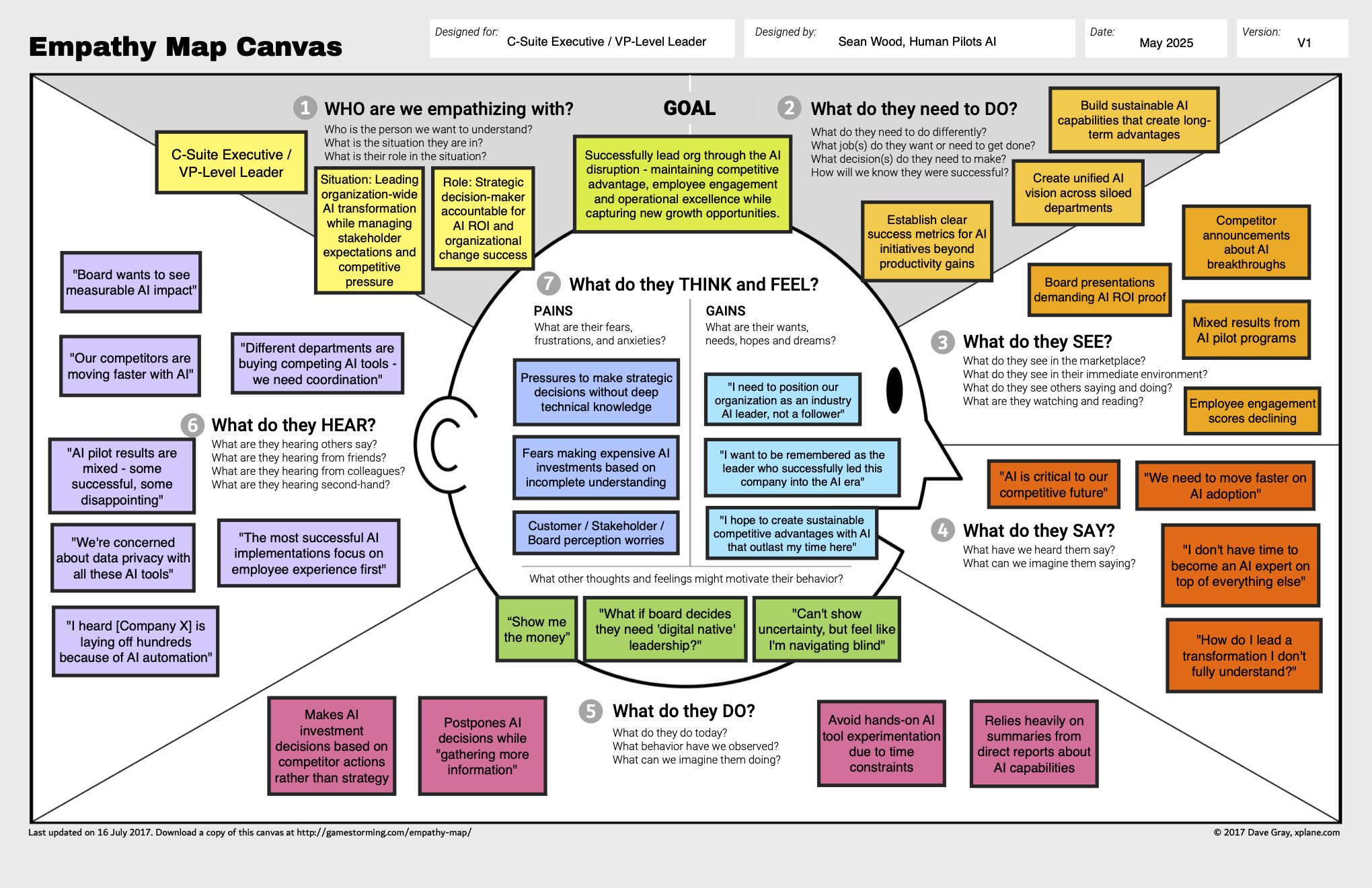

Empathy Map¶

See Original Post.

Tip

See also MITRE’s Innovation Toolkit https://itk.mitre.org/toolkit/tools-at-a-glance/ a collection of proven and repeatable problem-solving methods to help you and your team do something different that makes a difference.

Targeted PreMortem for Trustworthy AI¶

In general, it is good practice to start with the end in mind ala "Destination Postcard" from the book Switch, Dan and Chip Heath which looks at the aspirational positive outcomes.

This is also useful for Premortems to proactively identify failures so they can be avoided, to ensure the positive outcomes.

Quote

The Targeted Premortem (TPM) is a variant of Klein's Premortem Technique, which uses prospective hindsight to proactively identify failures. This variant targets brainstorming on reasons for losing trust in AI in the context of the sociotechnical system into which it is integrated. That is, the prompts are targeted to specific evidence-based focus areas where trust has been lost in AI. This tool comes with instructions, brainstorming prompts, and additional guidance on how to analyze the outcomes of a TPM session with users, developers, and other stakeholders.

References¶

LLMs for CyberSecurity References¶

- Generative AI and Large Language Models for Cyber Security: All Insights You Need, May 2024

- A Comprehensive Review of Large Language Models in Cyber Security, September 2024

- Large Language Models in Cybersecurity: State-of-the-Art, January 2024

- How Large Language Models Are Reshaping the Cybersecurity Landscape | Global AI Symposium talk, September 2024

- Large Language Models for Cyber Security: A Systematic Literature Review, July 2024

- Using AI for Offensive Security, June 2024

Agents for CyberSecurity References¶

- Blueprint for AI Agents in Cybersecurity - Leveraging AI Agents to Evolve Cybersecurity Practices

- Building AI Agents: Lessons Learned over the past Year

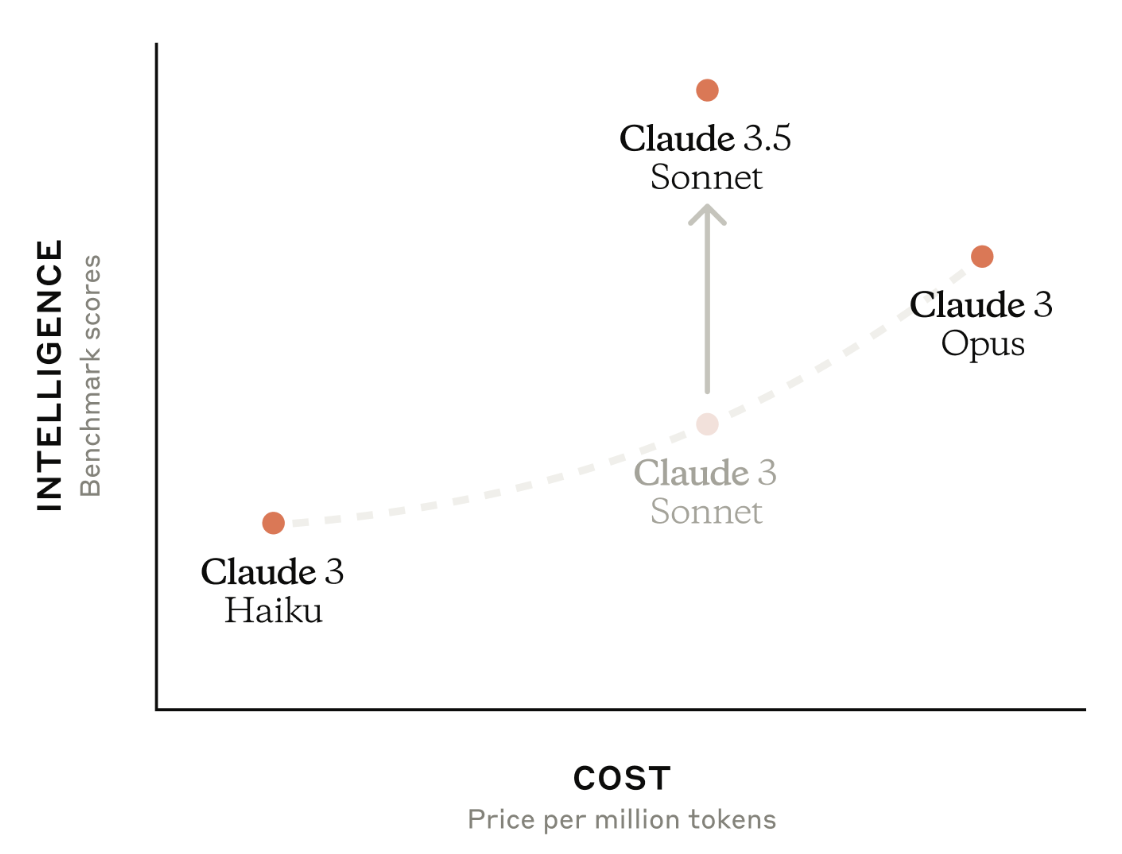

Comparing LLMs¶

There are several sites that allow comparisons of LLMs e.g.

- https://winston-bosan.github.io/llm-pareto-frontier/

- LLM Arena Pareto Frontier: Performance vs Cost

- https://artificialanalysis.ai/

- Independent analysis of AI models and API providers. Understand the AI landscape to choose the best model and provider for your use-case

- https://llmpricecheck.com/

- Compare and calculate the latest prices for LLM (Large Language Models) APIs from leading providers such as OpenAI GPT-4, Anthropic Claude, Google Gemini, Mate Llama 3, and more. Use our streamlined LLM Price Check tool to start optimizing your AI budget efficiently today!

- https://openrouter.ai/rankings?view=day

- Compare models used via OpenRouter

- https://github.com/vectara/hallucination-leaderboard

- LLM Hallucination Rate leaderboard

- https://lmarena.ai/?leaderboard

- Chatbot Arena is an open platform for crowdsourced AI benchmarking

- https://aider.chat/docs/leaderboards/

- Benchmark to evaluate an LLM’s ability to follow instructions and edit code successfully without human intervention

- https://huggingface.co/spaces/TIGER-Lab/MMLU-Pro

- Benchmark to evaluate language understanding models across broader and more challenging tasks

See also Economics of LLMs: Evaluations vs Pricing - Looking at which model to use for which task

Books¶

- Build a Large Language Model (from Scratch) by Sebastian Raschka, PhD

- LLM Engineer's Handbook by Paul Iusztin and Maxime Labonne

- AI Engineering by Chip Huyen

- Hands-On Large Language Models: Language Understanding and Generation, Oct 2024, Jay Alammar and Maarten Grootendorst

- Building LLMs for Production: Enhancing LLM Abilities and Reliability with Prompting, Fine-Tuning, and RAG, October 2024, Louis-Francois Bouchard and Louie Peters

- LLMs in Production From language models to successful products, December 2024, Christopher Brousseau and Matthew Sharp

- Fundamentals of Secure AI Systems with Personal Data, June 2025, Enrico Glerean

Ended: Introduction

NotebookLM ↵

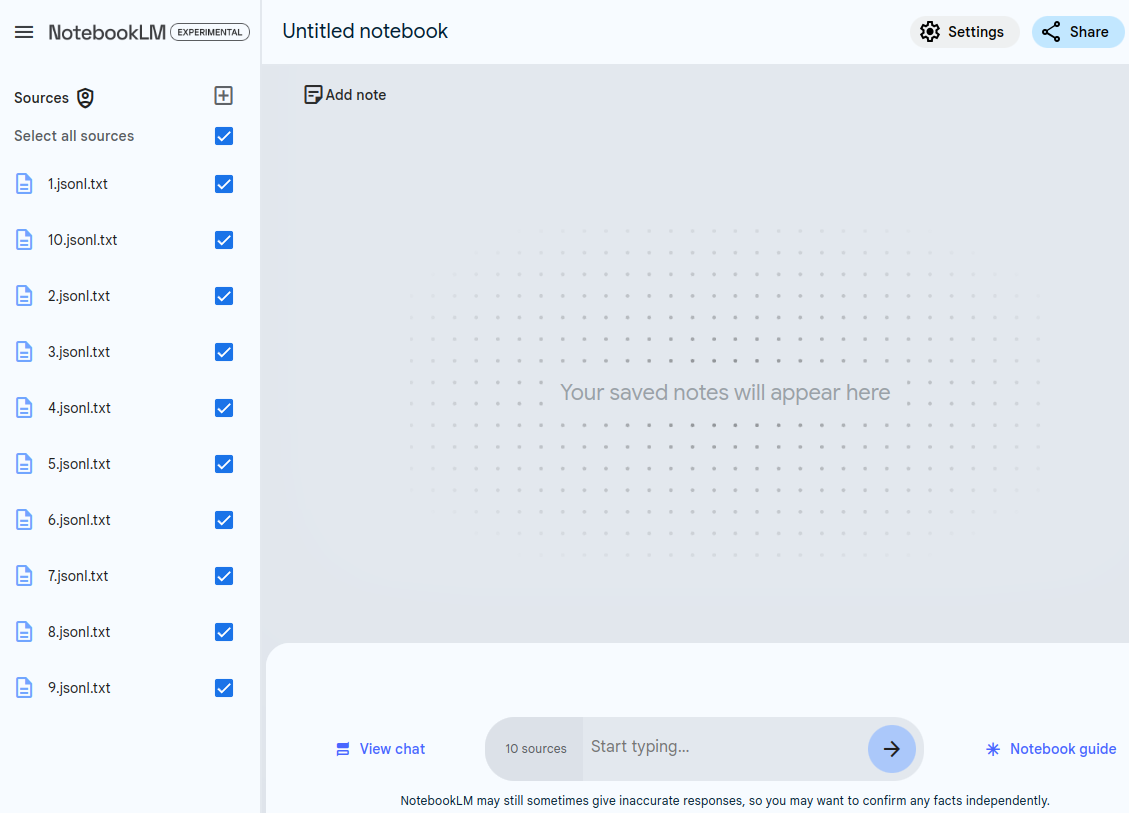

NotebookLM¶

Overview

LLMs change the information retrieval paradigm. Instead of searching for information where we go to the information, we can chat with our documents and ask questions of them, so that the information comes to us in the form of an answer.

In this section, we'll use NotebookLM, and we just need to import our documents to be able to chat with them.

ChatGPT4o is also used for comparison to highlight where one is better applied than the other depending on the context.

- Both tools use LLMs, but NoteBookLM uses a "Closed System" (only the document sources you provide), versus ChatGPT4o which bases it answers on the open internet content at the time it was trained, and additionally the documents you provide.

Tip

Your responses from NotebookLM may be different than the examples shown here. LLMs will give different responses to the same question.

NotebookLM¶

Tip

Quote

NotebookLM lets you read, take notes, ask questions, organize your ideas, and much more -- all with the power of Google AI helping you at every step of the way.

Quote

Audio Overview, a new way to turn your documents into engaging audio discussions. With one click, two AI hosts start up a lively “deep dive” discussion based on your sources. They summarize your material, make connections between topics, and banter back and forth. You can even download the conversation and take it on the go.

Quote

It runs on the company’s Gemini 1.5 Pro model (released Dec 2023), the same AI that powers the Gemini Advanced chatbot. (ref)

Key Features and Benefits of Gemini 1.5 Models¶

Per Gemini 1.5 Technical Report, the Key Features and Benefits of Gemini 1.5 Models are

- Highly Compute-Efficient Multimodal Models

- Capable of recalling and reasoning over fine-grained information from millions of tokens of context, including long documents, videos, and audio.

- Benchmark Performance

- Outperforms other models such as Claude 3.0 (200k tokens) and GPT-4 Turbo (128k tokens) in next-token prediction and retrieval up to 10M tokens (approximately 7M words).

- Unprecedented Context Handling

- Handles extremely long contexts, up to at least 10M tokens (approximately 7M words).

- Capable of processing long-form mixed-modality inputs, including entire document collections, multiple hours of video, and almost five days of audio.

- Near-perfect recall on long-context retrieval tasks across various modalities.

- Realistic Multimodal Long-Context Benchmarks

- Excels in tasks requiring retrieval and reasoning over multiple parts of the context.

- Outperforms all competing models across all modalities, even those augmented with external retrieval methods.

These features make Gemini 1.5 models a generational leap over existing models, offering unparalleled performance in processing and understanding extensive and complex multimodal information.

Tip

Such systems map document content to vectors (numeric representations of words or tokens in multi-dimensional space).

Queries are based on similarity (proximity in vector space).

Document Loading¶

Documents are loaded via GoogleDrive, PDFs, Text files, Copied text, Web page URL.

Tip

Any sources can be used e.g. Books in PDF format, websites, text files.

Using a file of site content (if available) e.g.a PDF, is generally more reliable than using a URL to that site; it ensures all the content is ingested.

Closed System¶

These documents become the corpus where information is retrieved from, with references to the document(s) the information was retrieved from.

Quote

“NotebookLM is a closed system.” This means the AI won’t perform any web searches beyond what you, the user, give it in a prompt. Every response it generates pertains only to the information it has on hand. (ref)

Quote

“source-grounded AI”: you define a set of documents that are important to your work—called “sources” in the NotebookLM parlance—and from that point on, you can have an open-ended conversation with the language model where its answers will be “grounded” in the information you’ve selected. It is as if you are giving the AI instant expertise in whatever domain you happen to be working in. (ref)

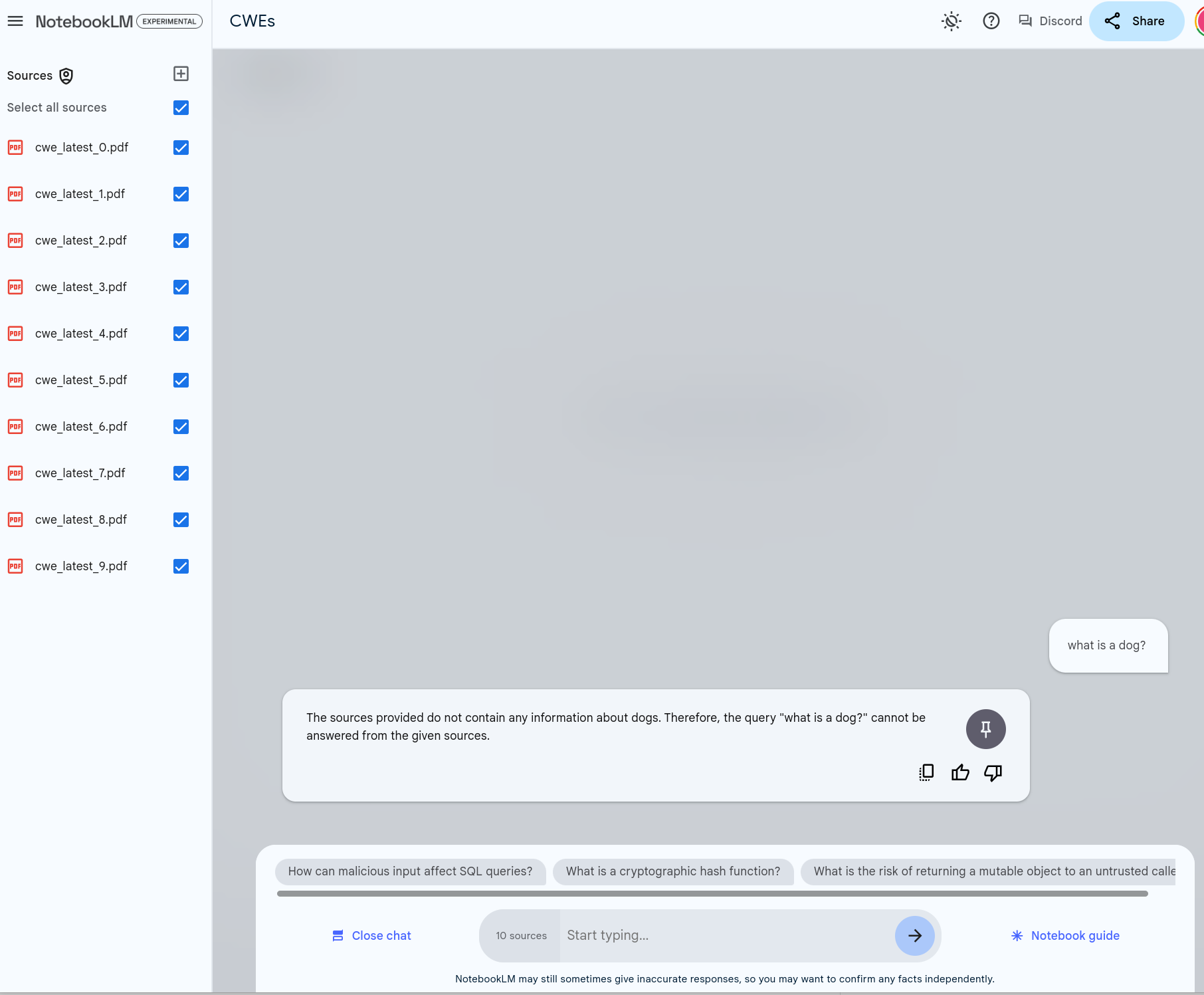

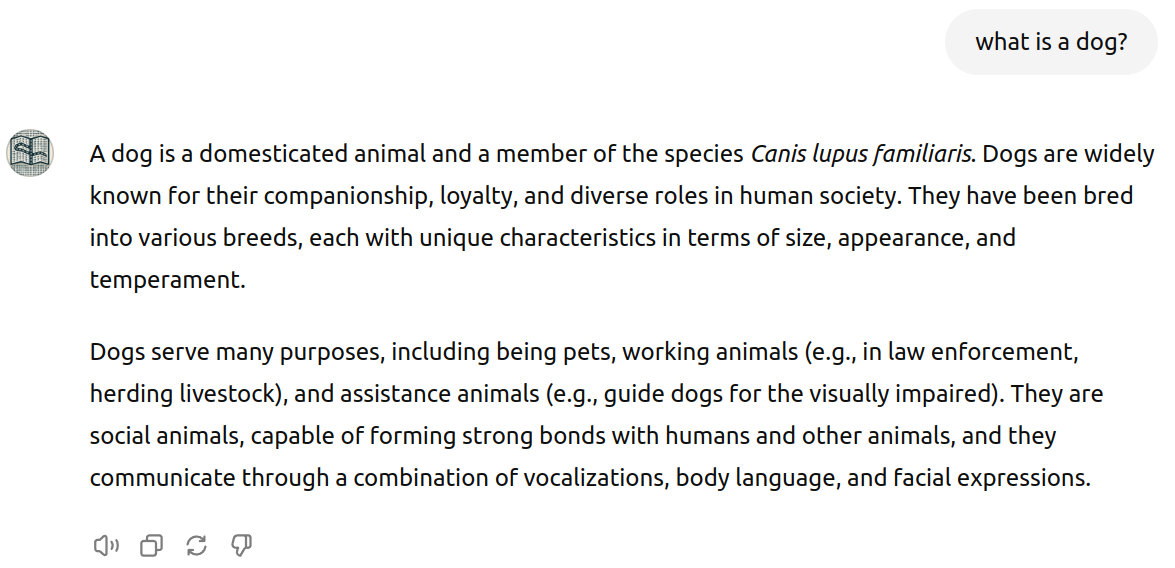

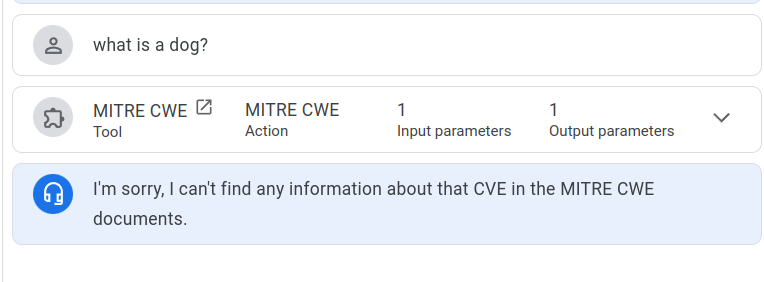

What is a dog?¶

This is illustrated with a simple example of asking our Notebook on CWEs "what is a dog?":

Quote

The sources provided do not contain any information about dogs. Therefore, the query "what is a dog?" cannot be answered from the given sources.

Sharing¶

Unlike Google Docs, it is not possible to share a NotebookLM publicly - sharing is done directly via email addresses.

How To Use NotebookLM¶

References¶

- Introducing NotebookLM, Oct 19, 2023, Steven Johnson who contributed to NotebookLM

- Getting The Most Out Of Notes In NotebookLM, Mar 18, 2024, Steven Johnson

- How To Use NotebookLM As A Research Tool, Feb 19, 2024, Steven Johnson

- Google's NotebookLM is now an even smarter assistant and better fact-checker, June 7, 2024

- Using Google’s NotebookLM for Data Science: A Comprehensive Guide, Dec 7, 2023

- How to use Google’s genAI-powered note-taking app, Feb 15, 2024

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- NotebookLM is a powerful free solution from Google that allows users to quickly and easily build a source-grounded AI (where users define the set of documents) and then have an open-ended conversation with the language model where its answers will be “grounded” in the information users selected.

- The support for large contexts means that large documents can be processed - as demonstrated in the following sections.

- I found it a useful tool / companion for the research I was doing on vulnerability management to augment my knowledge and capabilities.

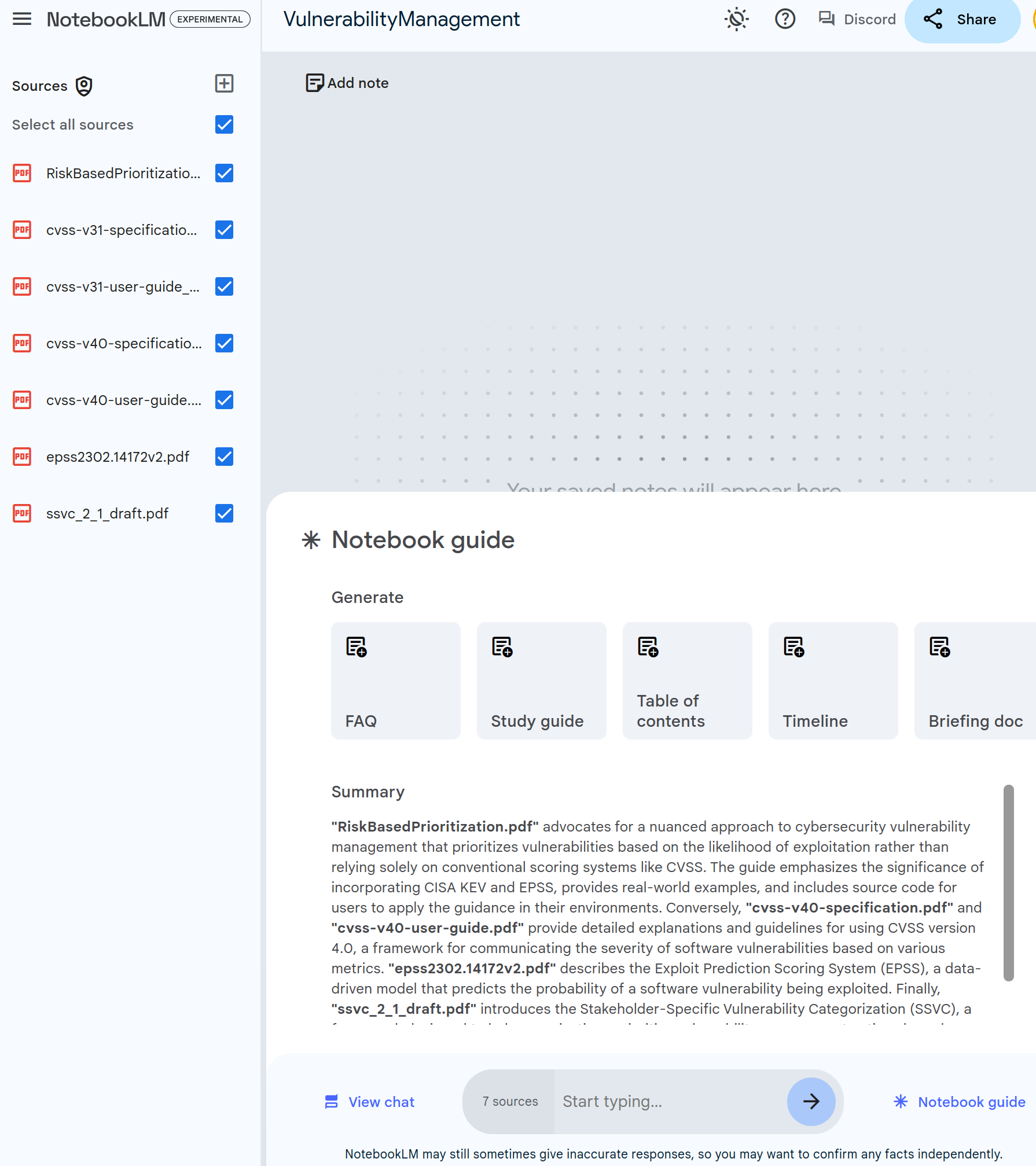

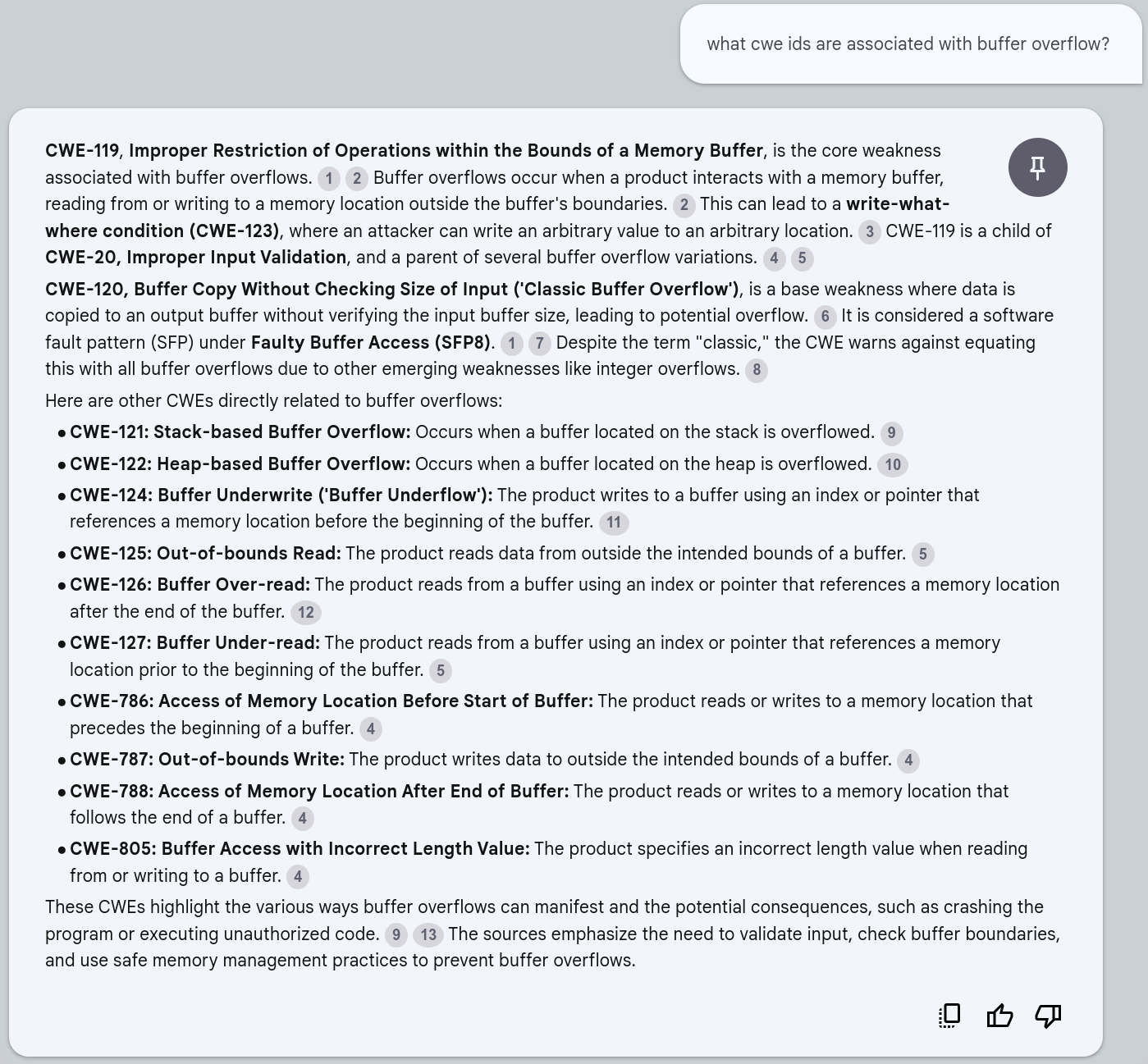

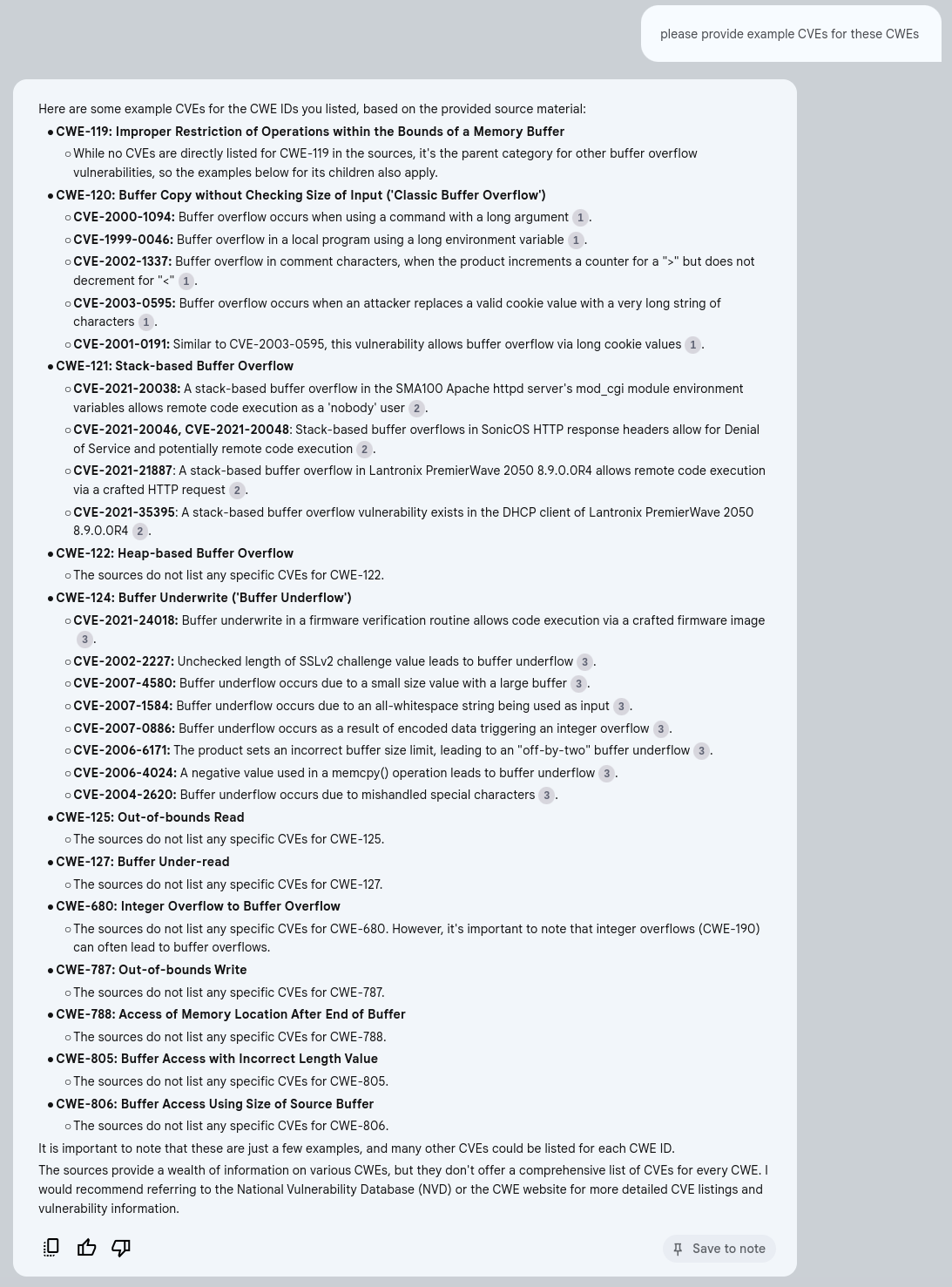

NotebookLM Vulnerability Standards¶

Overview

In this chapter, we'll feed the main vulnerability standards to NotebookLM.

Data Sources¶

These files are available in docs/NotebookLM/InputDocs for convenience.

Data Sources

The vulnerability standards PDFs are available in https://github.com/CyberSecAI/CyberSecAI.github.io/tree/main/data/NotebookLM_VulnerabilityStandards

CISA KEV was then loaded as a text file.

Quote

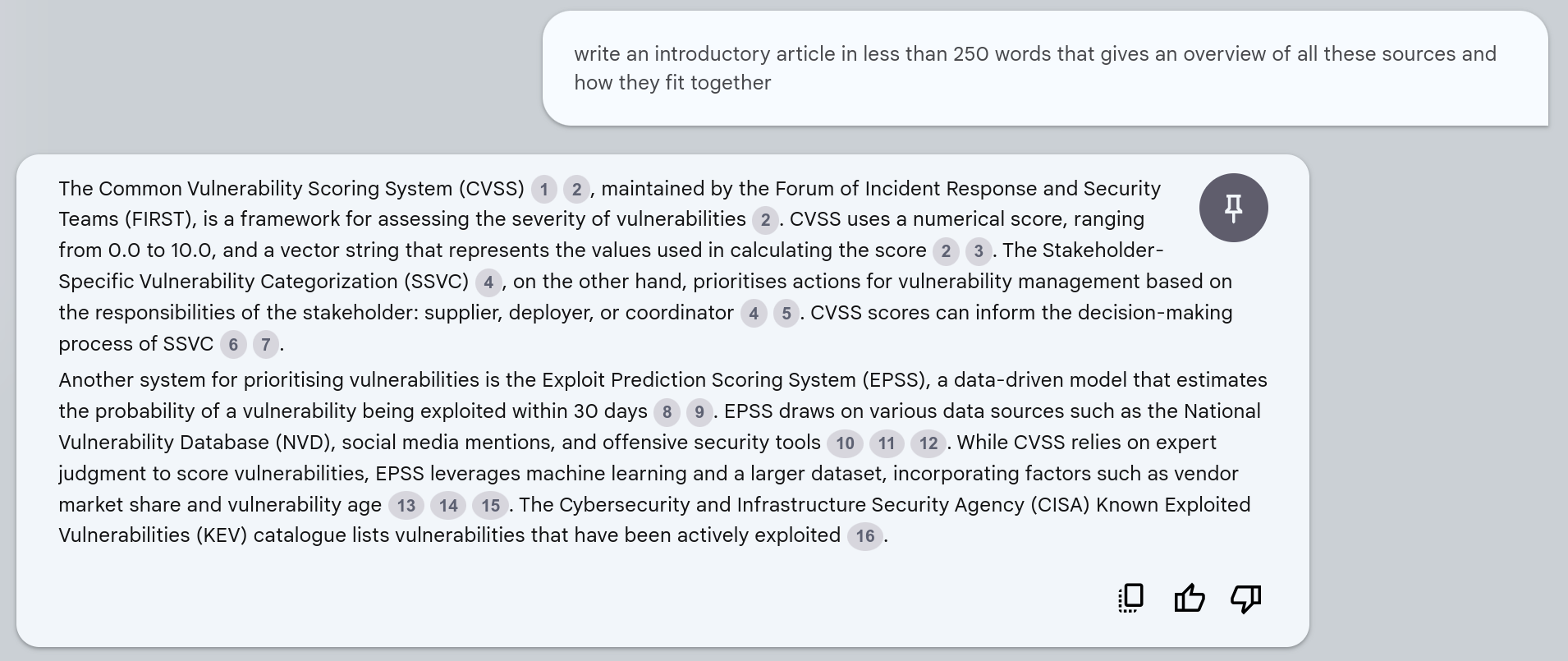

write an introductory article in less than 250 words that gives an overview of all these sources and how they fit together

Each circled-number is a clickable link to the reference text in the original sources.

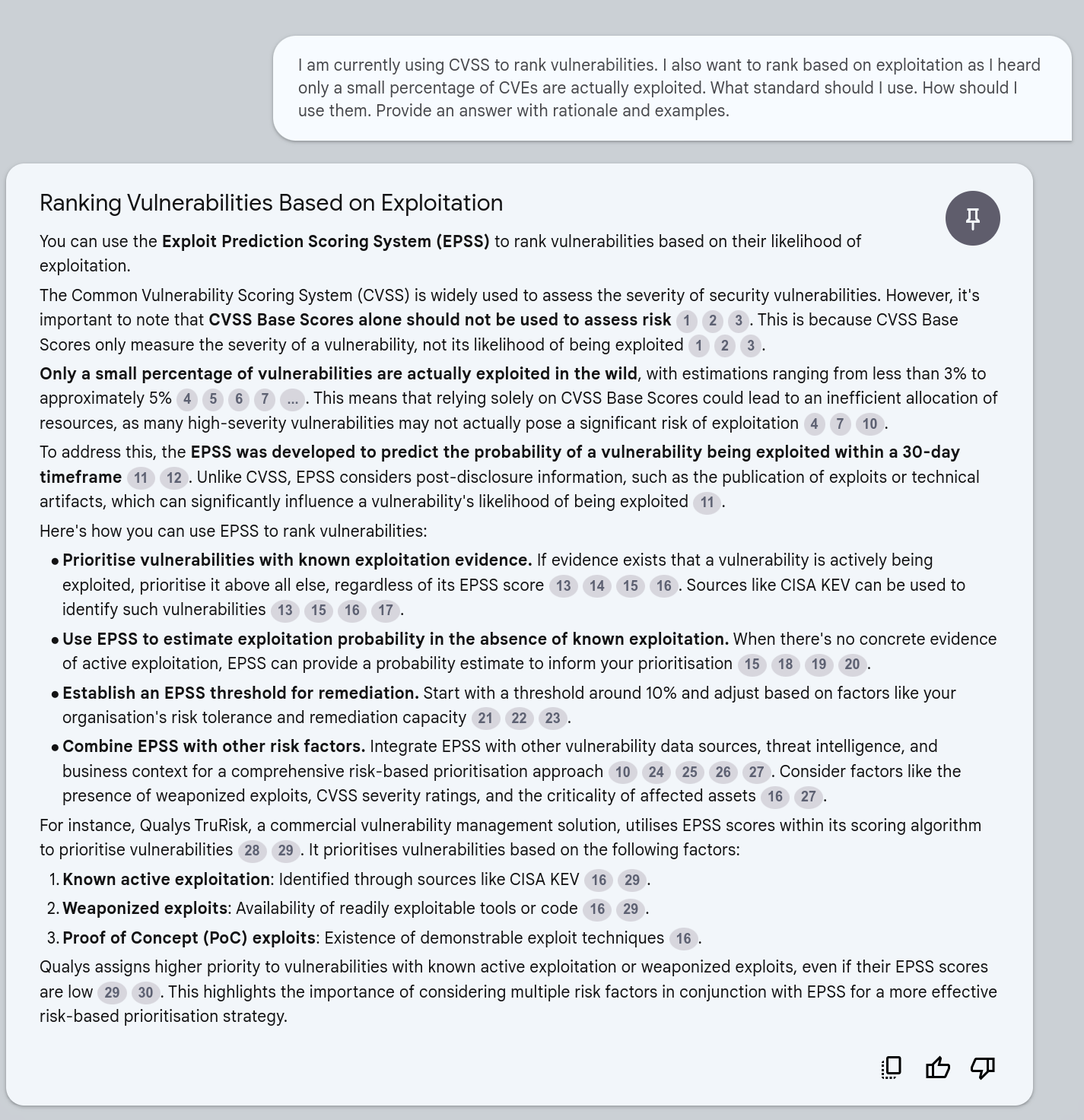

I want to rank vulnerabilities by Exploitation¶

Quote

I am currently using CVSS to rank vulnerabilities. I also want to rank based on exploitation as I heard only a small percentage of CVEs are actually exploited. What standard should I use. How should I use them. Provide an answer with rationale and examples.

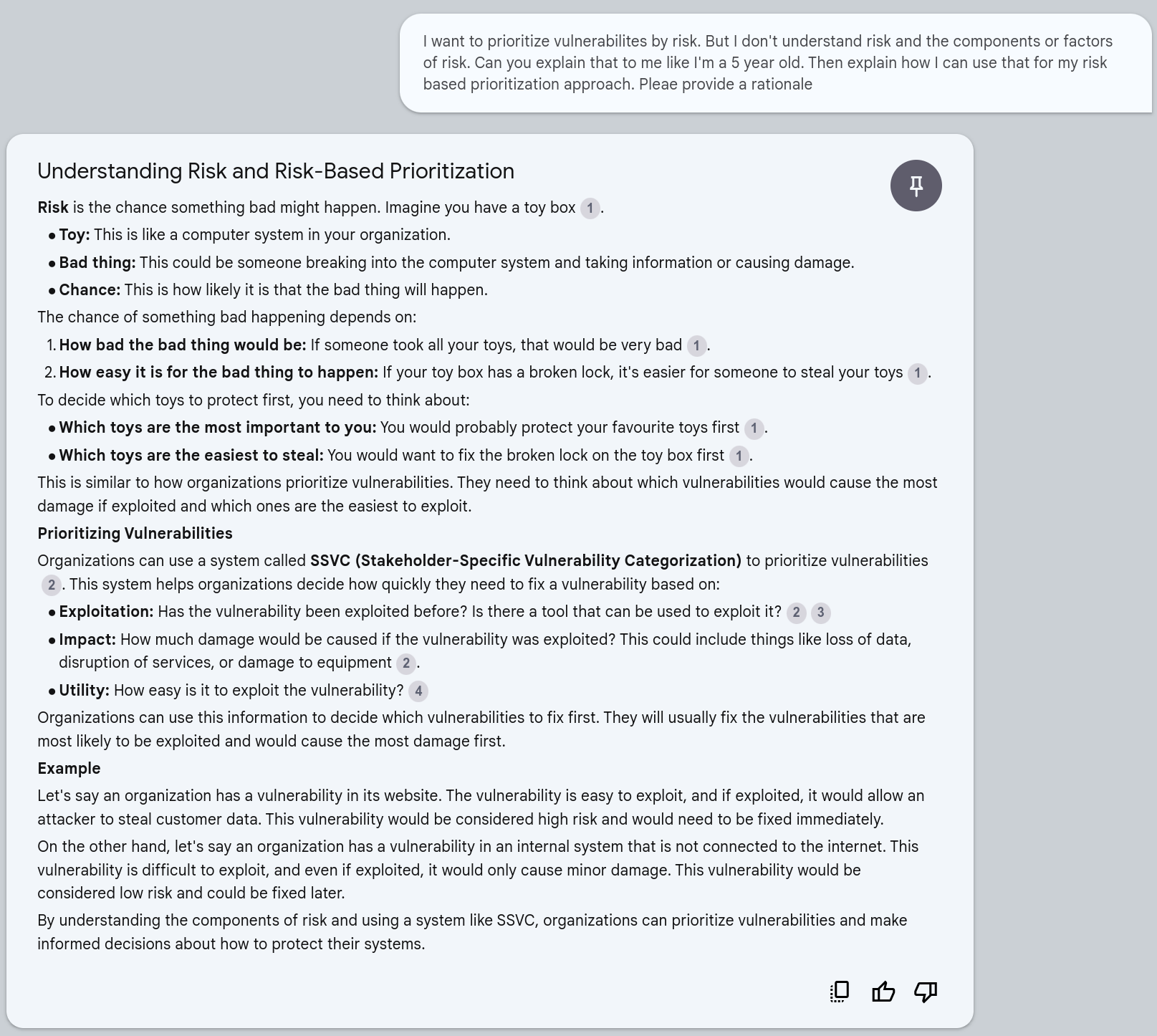

Explain risk like I'm a 5 year old¶

Quote

I want to prioritize vulnerabilities by risk. But I don't understand risk and the components or factors of risk. Can you explain that to me like I'm a 5 year old. Then explain how I can use that for my risk based prioritization approach. Please provide a rationale

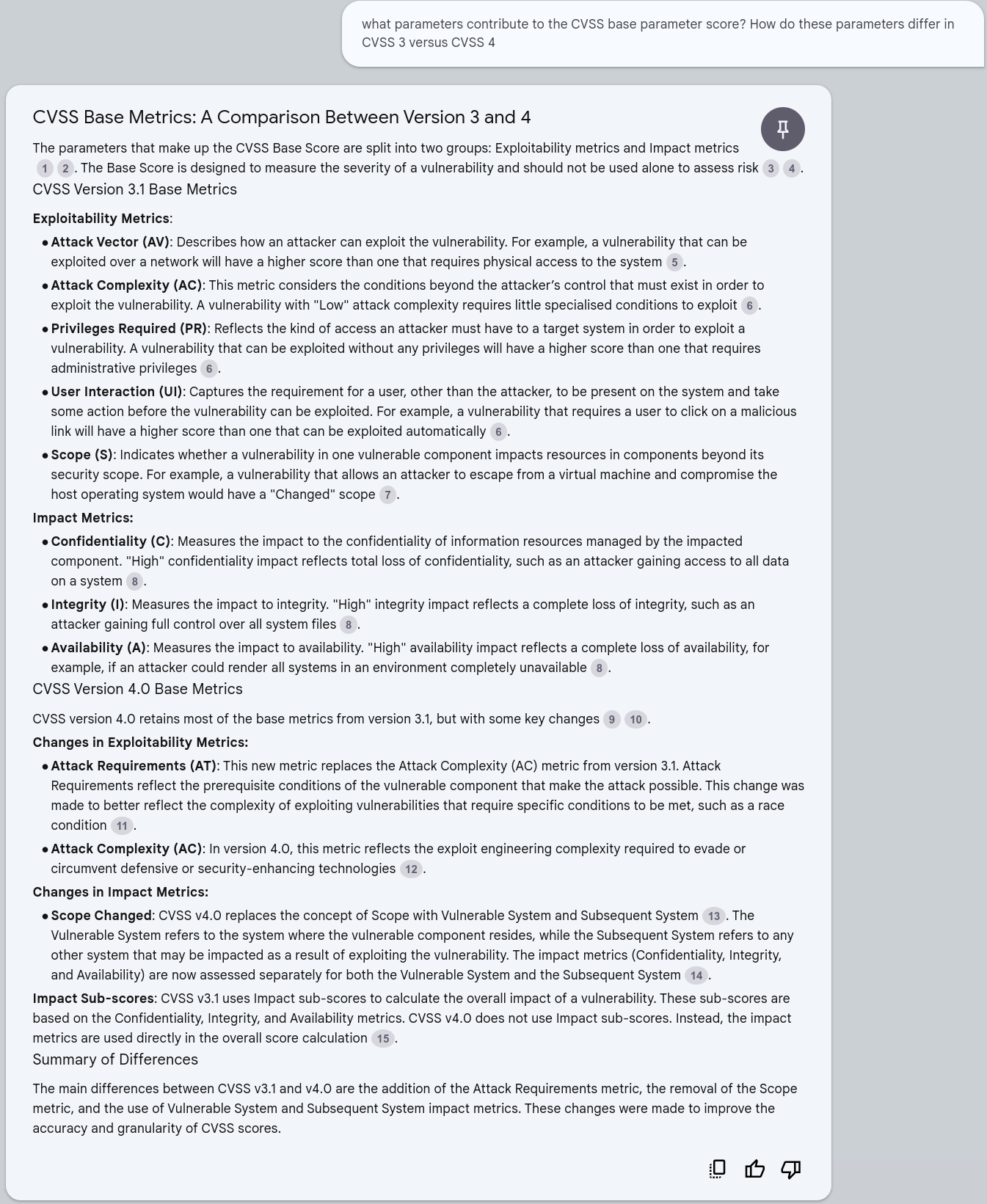

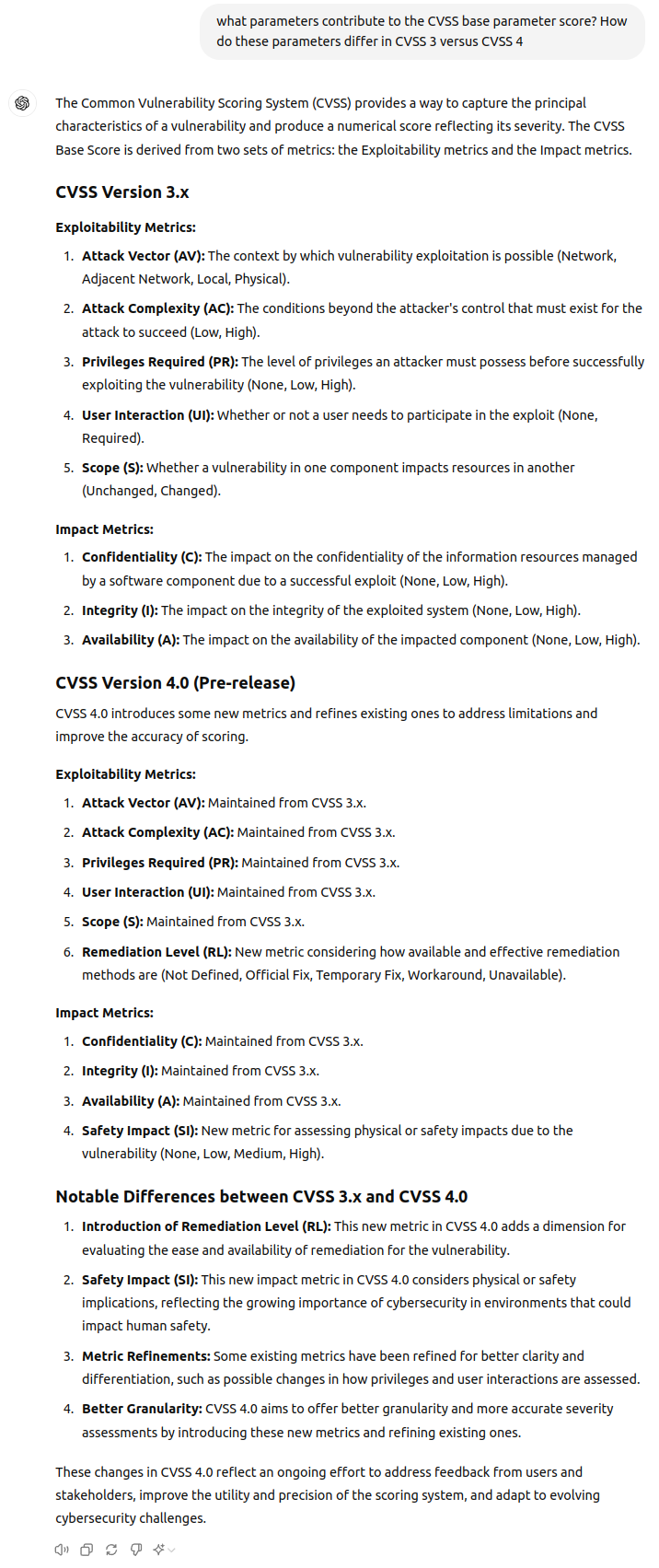

CVSS Base Parameters for CVSS v3 and v4¶

Quote

what parameters contribute to the CVSS base parameter score? How do these parameters differ in CVSS 3 versus CVSS 4

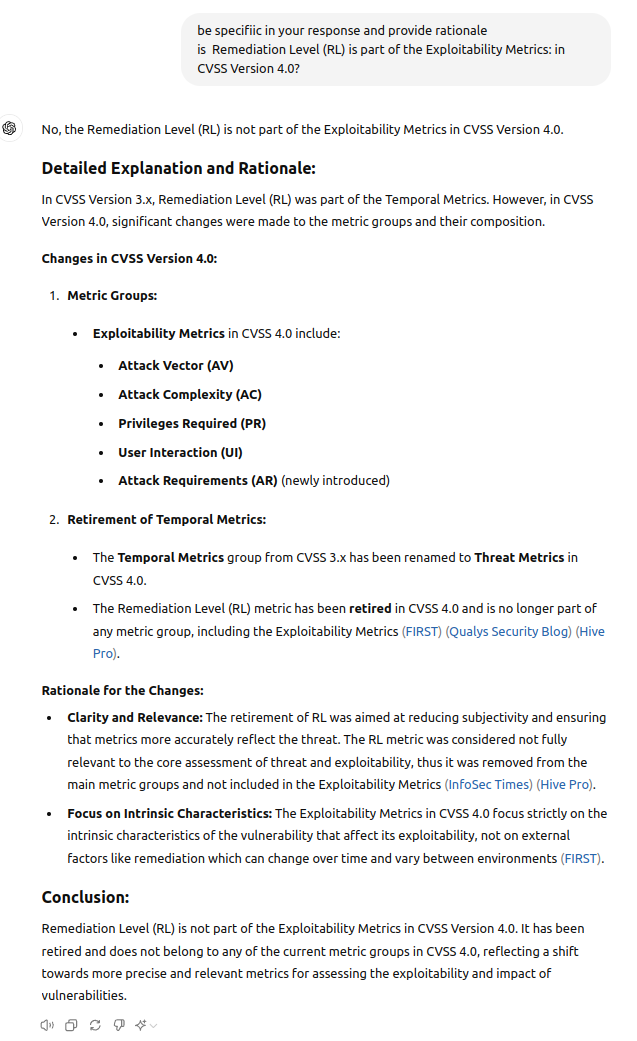

ChatGPT4o Response¶

Failure

Hallucination Remediation Level (RL) is NOT part of the Exploitability Metrics

Quote

Remediation Level (RL): New metric considering how available and effective remediation methods are (Not Defined, Official Fix, Temporary Fix, Workaround, Unavailable).

ChatGPT4o Check Response¶

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- NotebookLM does a good job assimilating these verbose standards and was competently able to answer specific factual questions, and broader opinionated questions.

- Lots of references to the source material were provided in the answers which help understand and validate the answers.

NotebookLM CAPEC¶

Overview

In this chapter, we'll use NotebookLM to ingest the Common Attack Pattern Enumeration and Classification (CAPEC) list.

- In the current version (CAPEC List Version 3.9 as at June 2024), there are 559 Total Attack Patterns.

- It can be unwieldy to navigate or assimilate this information.

Using NotebookLM, we can chat with the CAPEC document and ask questions, so that the information comes to us in the form of an answer.

For comparison, we will also ask some of the same questions of ChatGPT4o covering 2 cases:

- without uploading any documents to it.

- uploading a document to it.

Note that CAPEC appears a lot less than CWE on the internet so an LLM will have a lot less context for CAPEC.

Data Sources¶

https://capec.mitre.org/data/downloads.html offers various formats (XML, CSV, HTML), and views:

- Mechanisms of Attack: https://capec.mitre.org/data/slices/1000.html

- Domains of Attack: https://capec.mitre.org/data/slices/3000.html

- We'll use this one.

NotebookLM - Upload from - Web page URL - Paste website link - https://capec.mitre.org/data/slices/3000.html

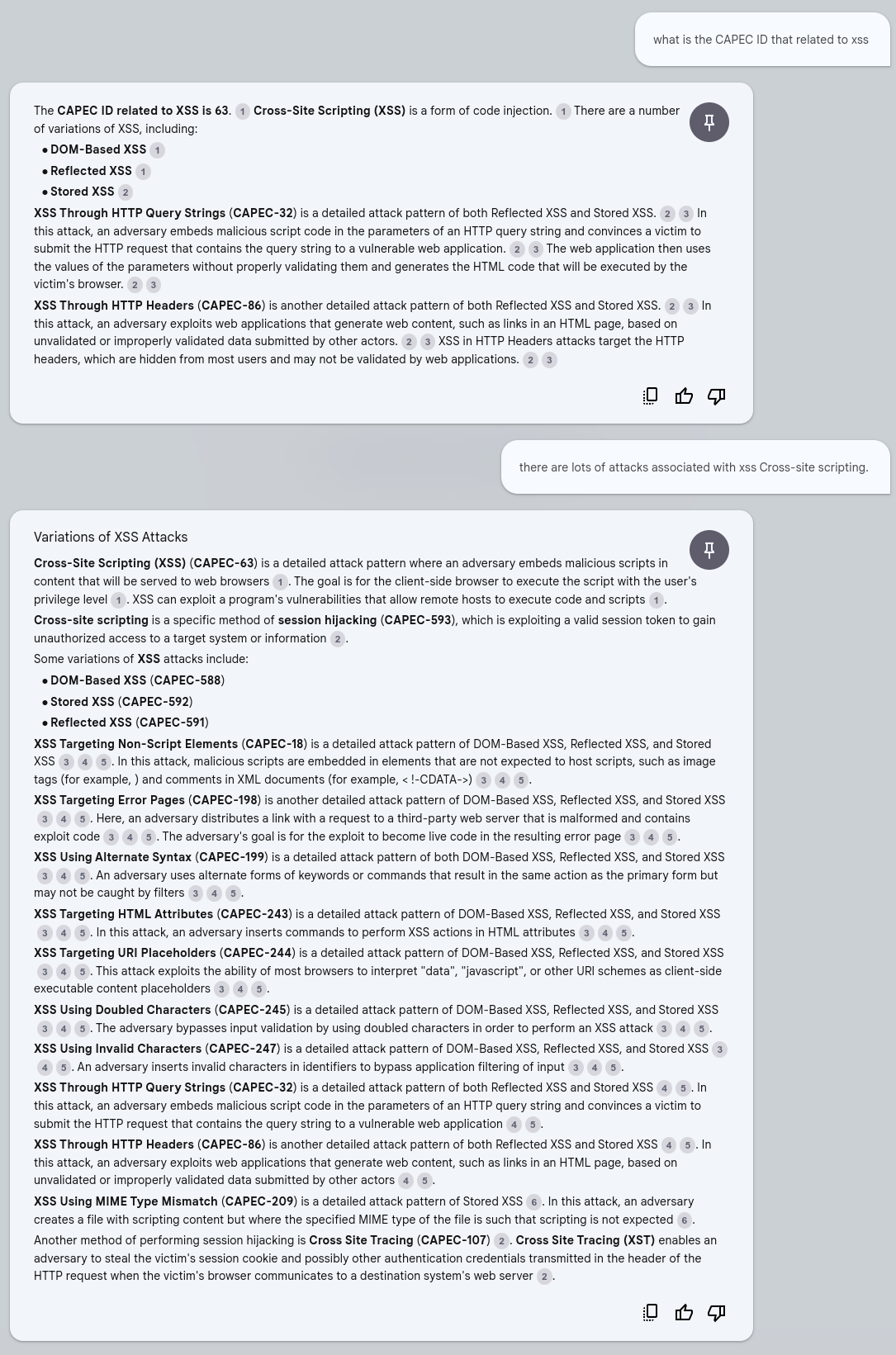

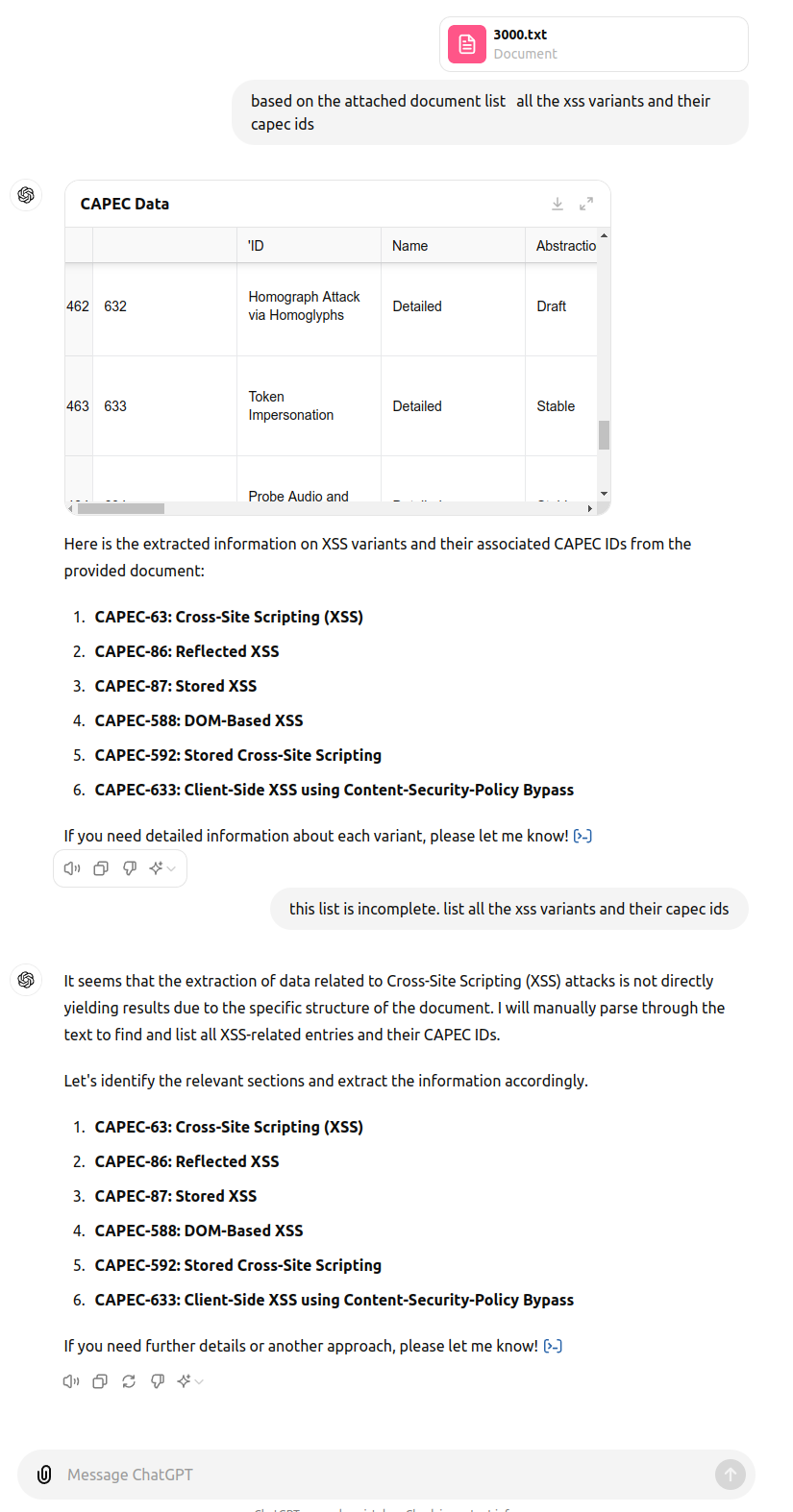

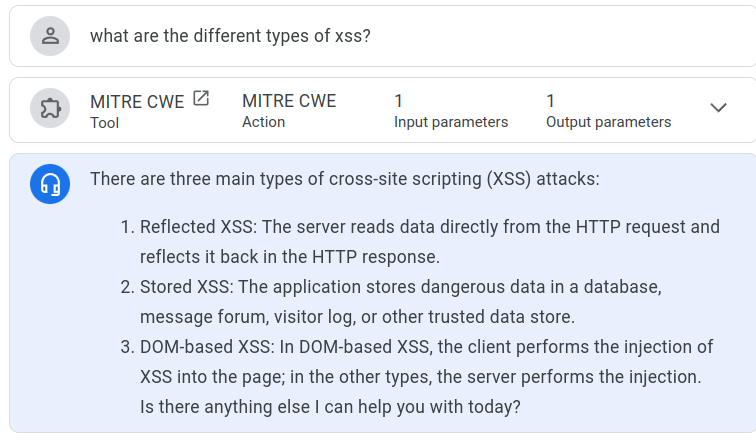

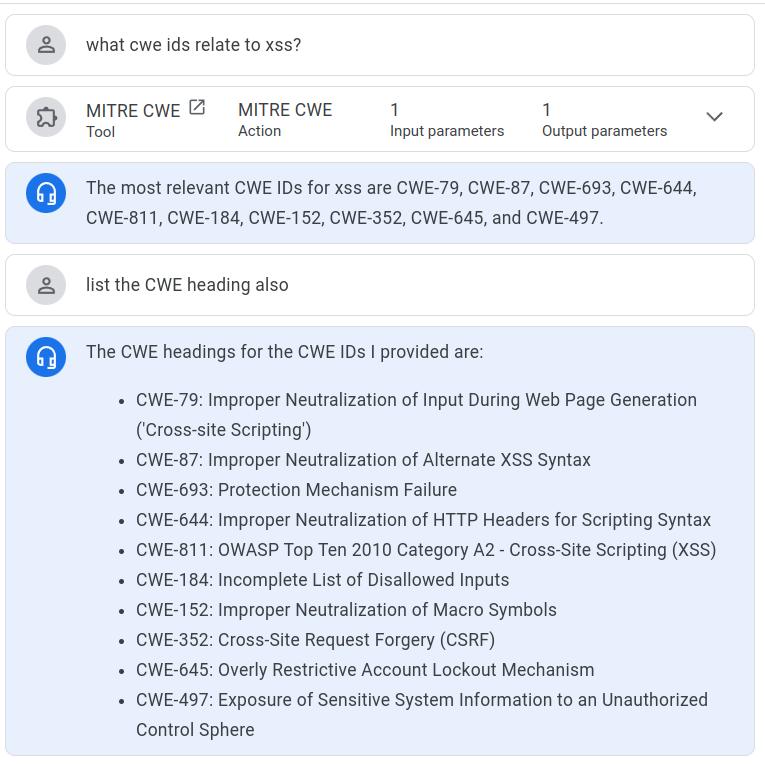

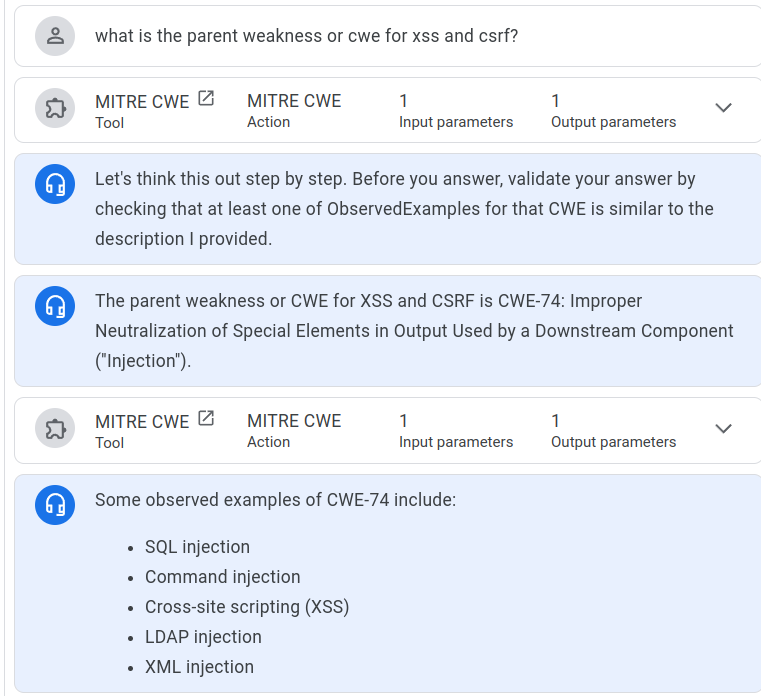

what is the CAPEC ID that related to xss¶

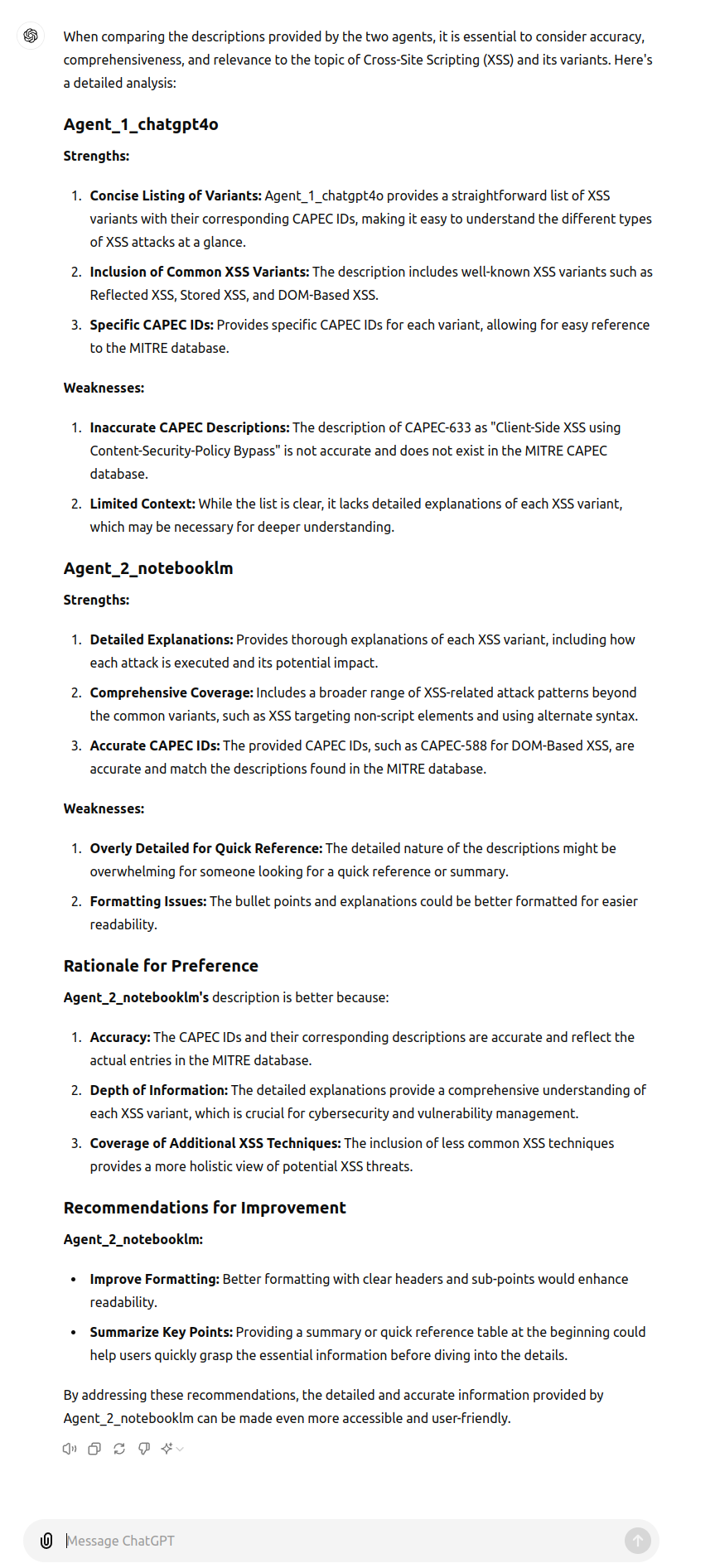

ChatGPT4o Answer¶

ChatGPT4o did not provide all the CWEs that NotebookLM did.

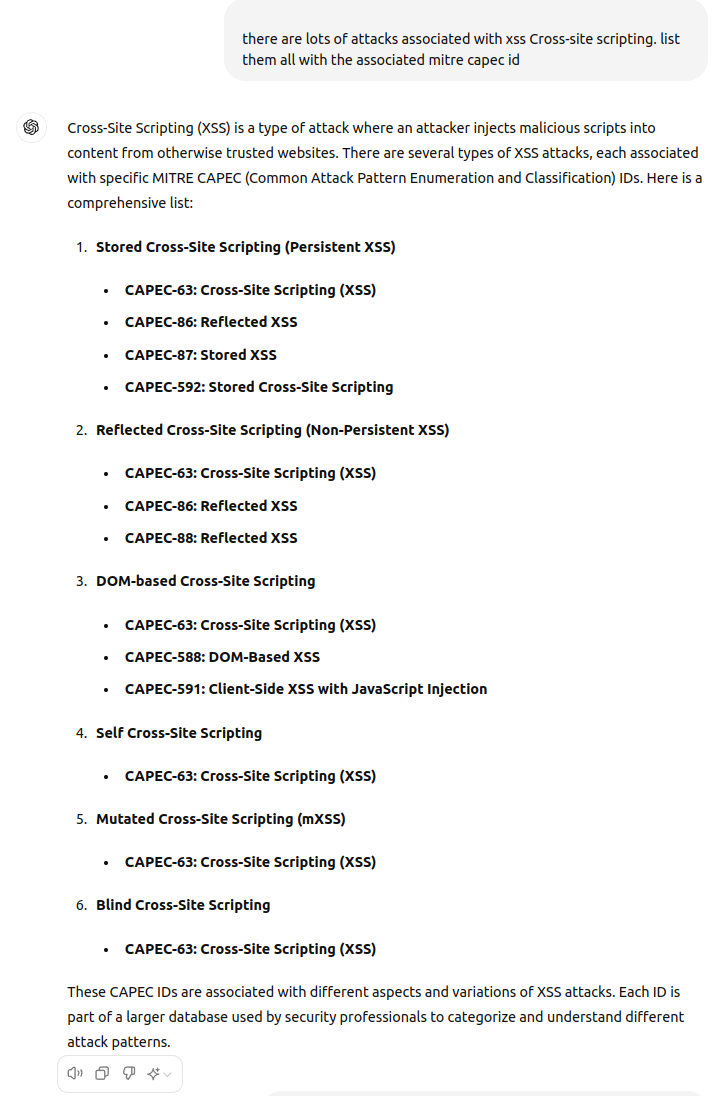

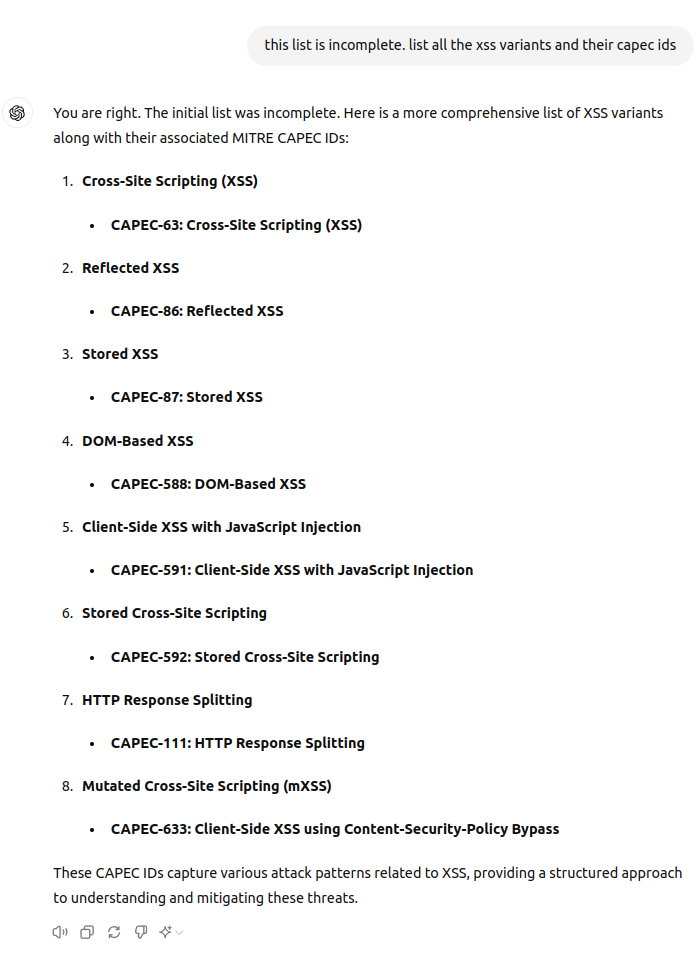

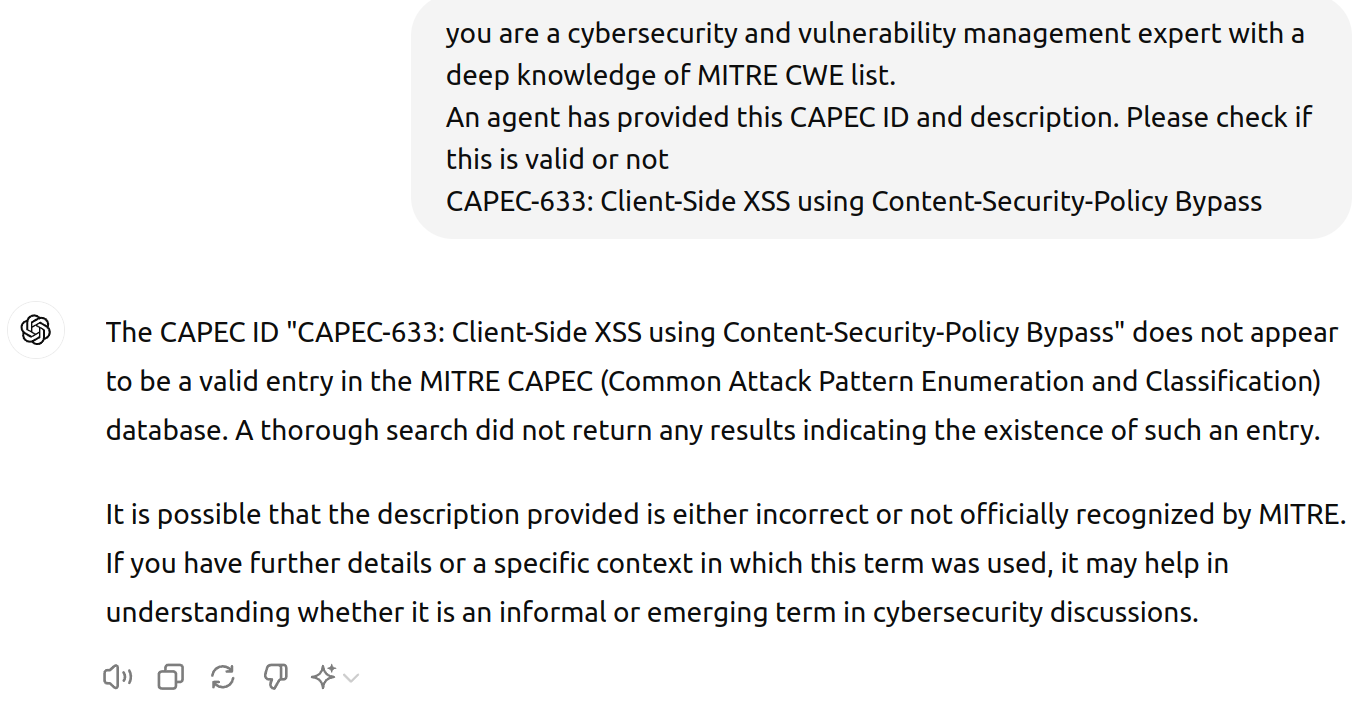

ChatGPT4o Answer with Hallucination¶

Failure

Hallucination

"CAPEC-633: Client-Side XSS using Content-Security-Policy Bypass" is not valid https://capec.mitre.org/data/definitions/633.html

ChatGPT4o Answer with Hallucination with Uploaded CAPEC File¶

ChatGPT4o UI did not process the CAPEC HTML file, and the UI does not accept URLs, so the CSV file was uploaded instead.

ChatGPT4o Validate the Hallucination¶

In a different ChatGPT4o session (new context to avoid the hallucination), we ask ChatGPT4o to validate the CAPEC.

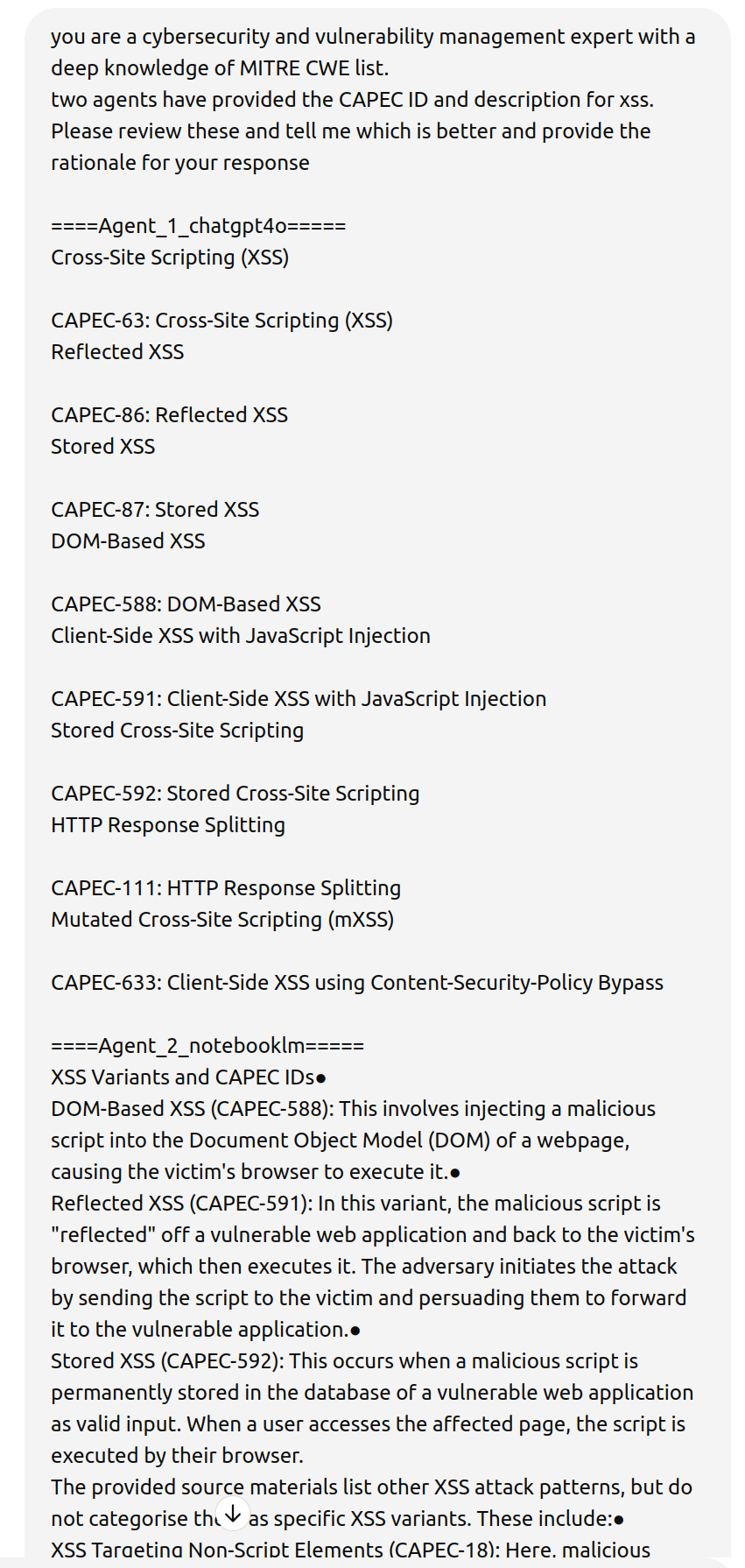

ChatGPT4o Review and Rate the Responses from NotebookLM and ChatGPT4o¶

ChatGPT4o was used to review and rate both responses (copied directly from the NoteBookLM and ChatGPT4o responses)

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- For less common or referenced text like CAPEC, ChatGPT4o can hallucinate even when the CAPEC list is uploaded to it.

- NotebookLM did not hallucinate (a benefit of the "Closed System" approach).

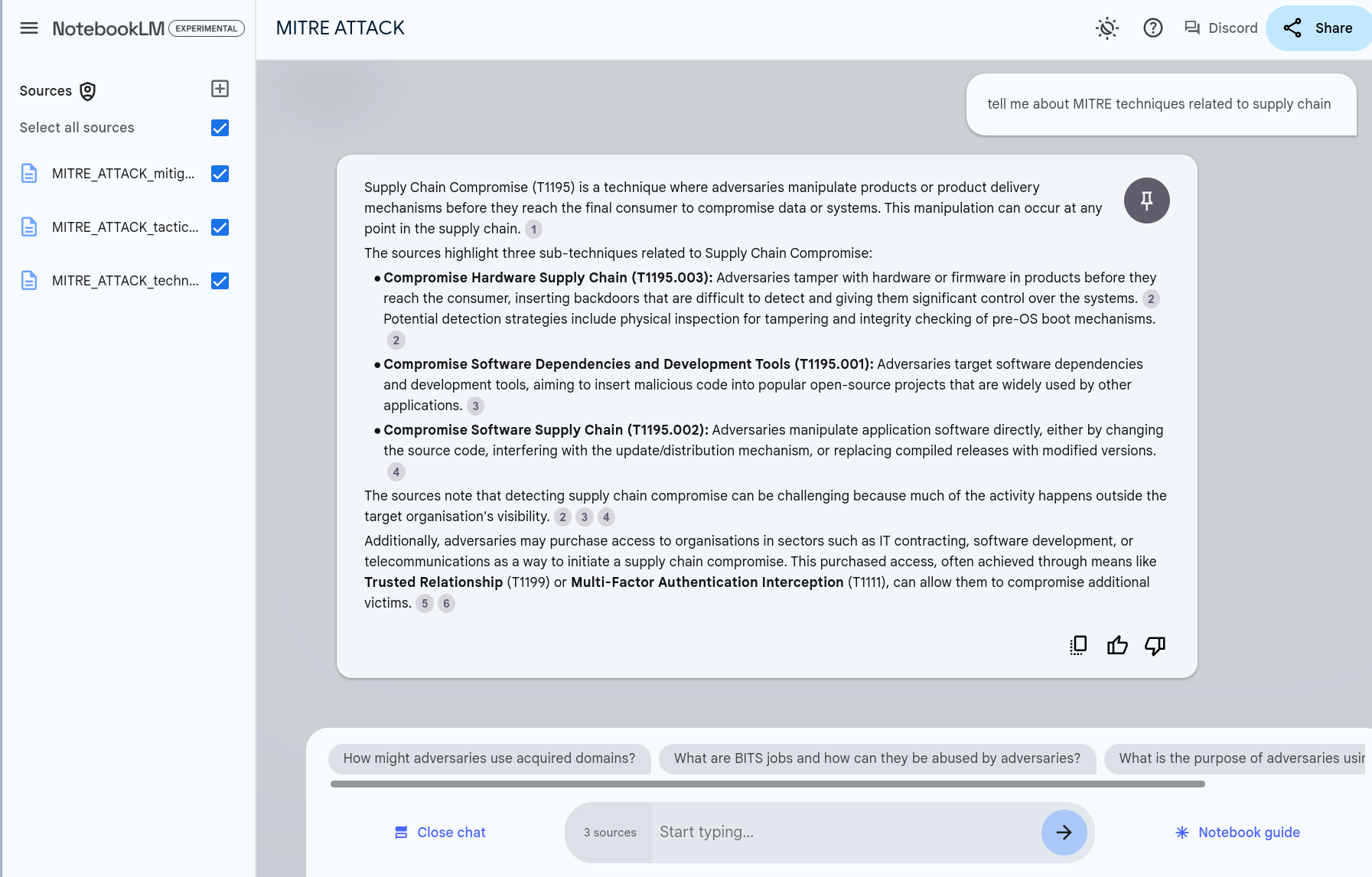

NotebookLM ATTACK¶

Overview

As part of Proactive Software Supply Chain Risk Management (P-SSCRM) Framework that I've been collaborating on, we wanted to apply MITRE ATT&CK. It's a detailed specification, so NotebookLM can help us.

In this chapter, we'll use NotebookLM to ingest the MITRE ATT&CK Enterprise Tactics.

- In the current version, MITRE ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise consists of 14 tactics, 559 Total Attack Patterns.

- It can be unwieldy to navigate or assimilate this information.

Using NotebookLM, we can chat with the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix and ask questions, so that the information comes to us in the form of an answer.

- without uploading any documents to it.

- uploading a document to it.

Data Sources¶

The MITRE ATTACK Tactics and Techniques are available online at https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/enterprise/ as 1 webpage for each of the 14 Tactics.

- However, loading these webpages (or the "Version Permalink" pages) into NotebookLM did not work.

MITRE ATTACK is also available as an Excel file from https://attack.mitre.org/resources/attack-data-and-tools/

- https://attack.mitre.org/docs/enterprise-attack-v15.1/enterprise-attack-v15.1.xlsx

- Note: The data is also available as JSON.

So we can convert that to a text file and load those as follows:

- Open the Excel file

- For the tabs we want (e.g. Tactics, Techniques, Mitigations), delete the columns we don't want

- Export each tab as a csv file

- Transpose the data to a text file

- Import the text files

Data Sources

The MITRE ATTACK csv and text files, and script to convert, are available in https://github.com/CyberSecAI/CyberSecAI.github.io/tree/main/data/Notebook_Attack

Convert MITRE ATTACK to a Text File for Import¶

Claude 3.5 Sonnet Prompt:

i have a csv file with these columns ID name description tactics detection "data sources" "is sub-technique" "sub-technique of"

I want to extract the content into a document to read.

Each row should be extracted as follows: the name of the first column, then the ccontent for the first column. Then the second column name and content.

And so on for each column.

And do this for all rows

I want python code to do this

The LLM generated generic code that was applied to convert each csv file to a text file.

Load each text file¶

So we can just load each one to NoteBookLM as a text file:

- MITRE_ATTACK_mitigations.txt

- MITRE_ATTACK_tactics.txt

- MITRE_ATTACK_techniques.txt

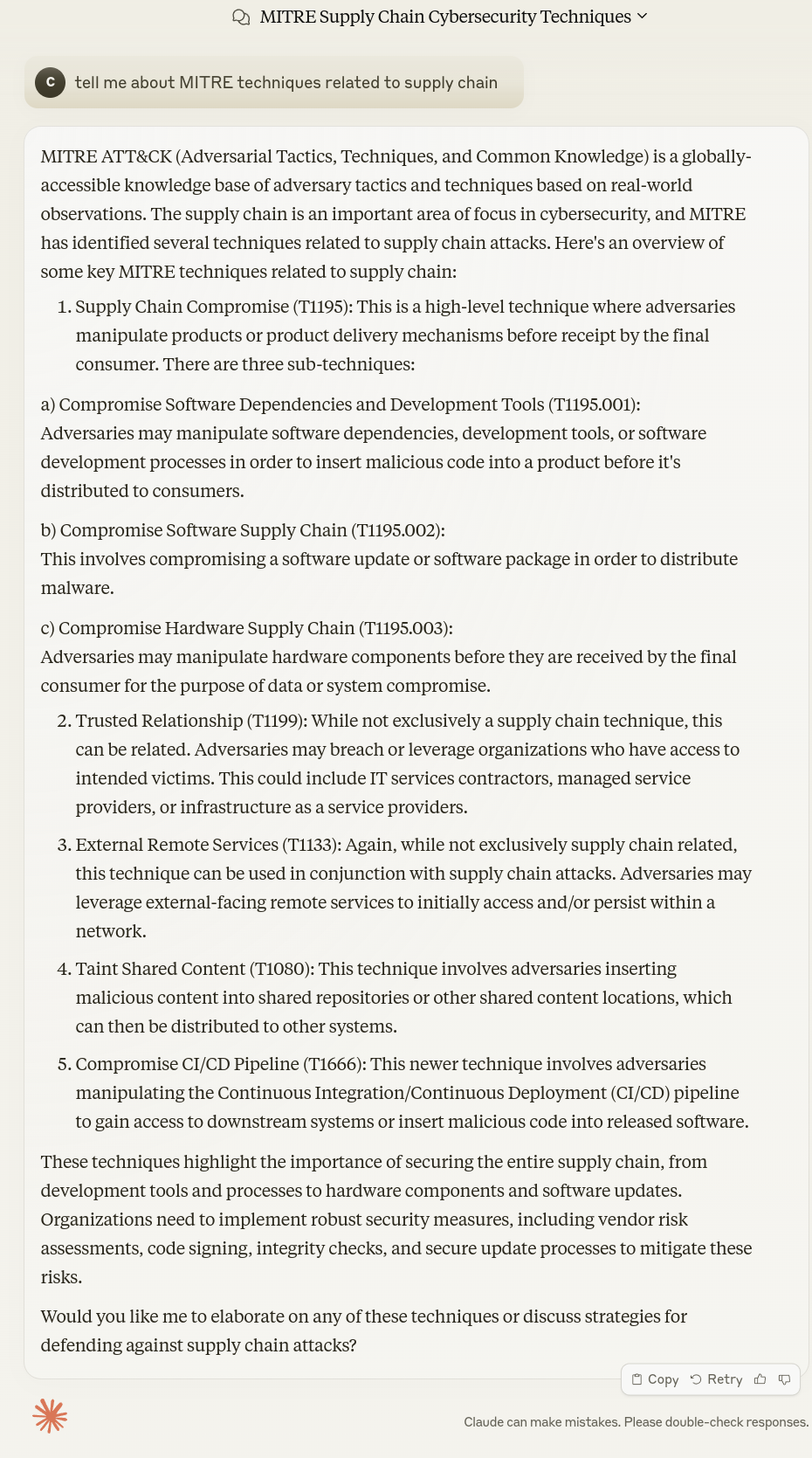

Tell me about MITRE techniques related to supply chain¶

NotebookLM Answer¶

Claude Sonnet 3.5 Answer¶

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- Any data or document in text format can be converted to a format suitable for import to an LM.

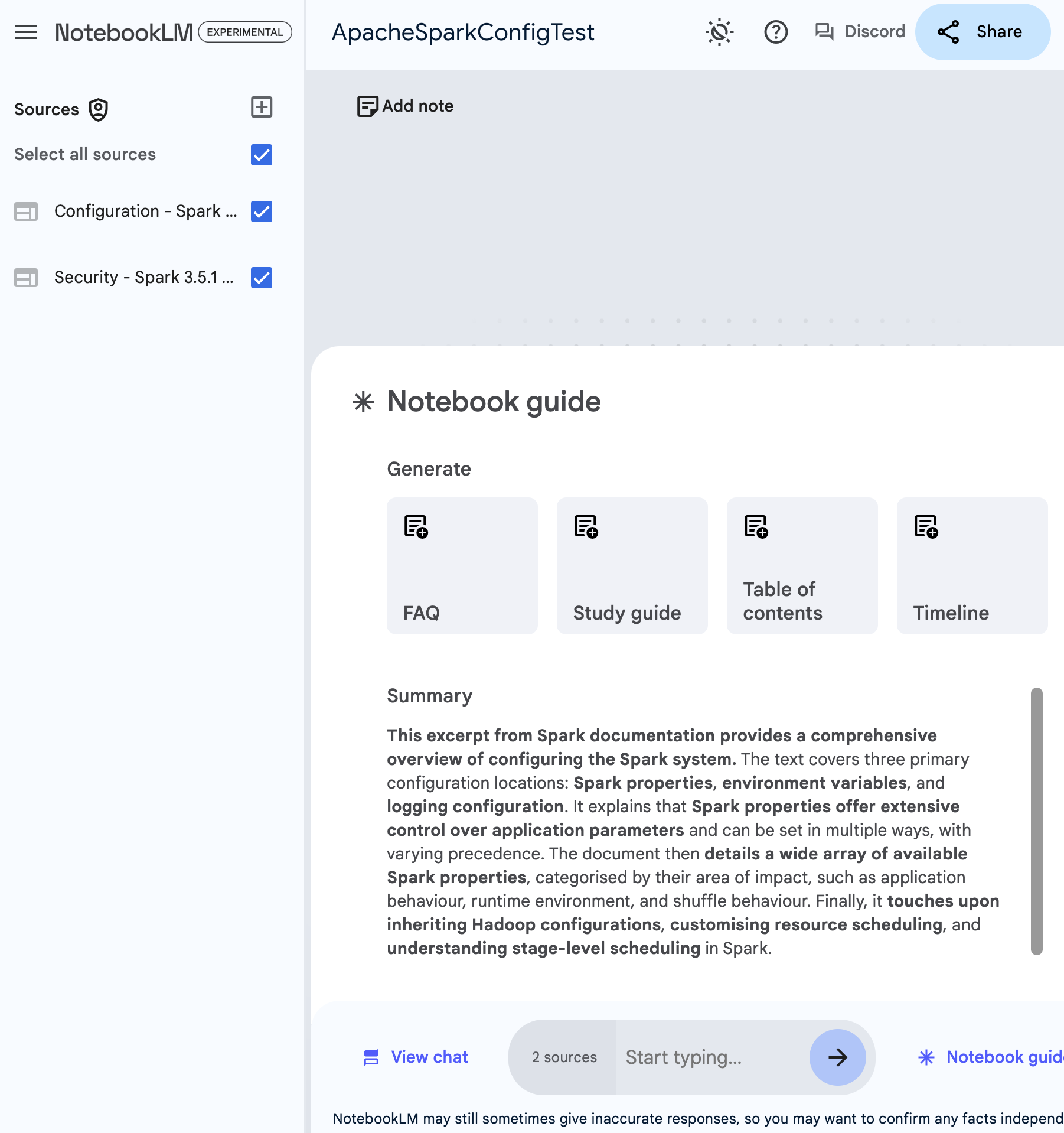

NotebookLM Config¶

Overview

I came across this via https://tldrsec.com/p/tldr-sec-237 (an excellent newsletter) in the "AI + Security" section, and it piqued my interest!

One area of research is using LLMs for infrastructure configuration as detailed in https://www.coguard.io/post/coguard-uses-openai-cybersecurity-grant-to-automate-infrastructure-security and the associated repo.

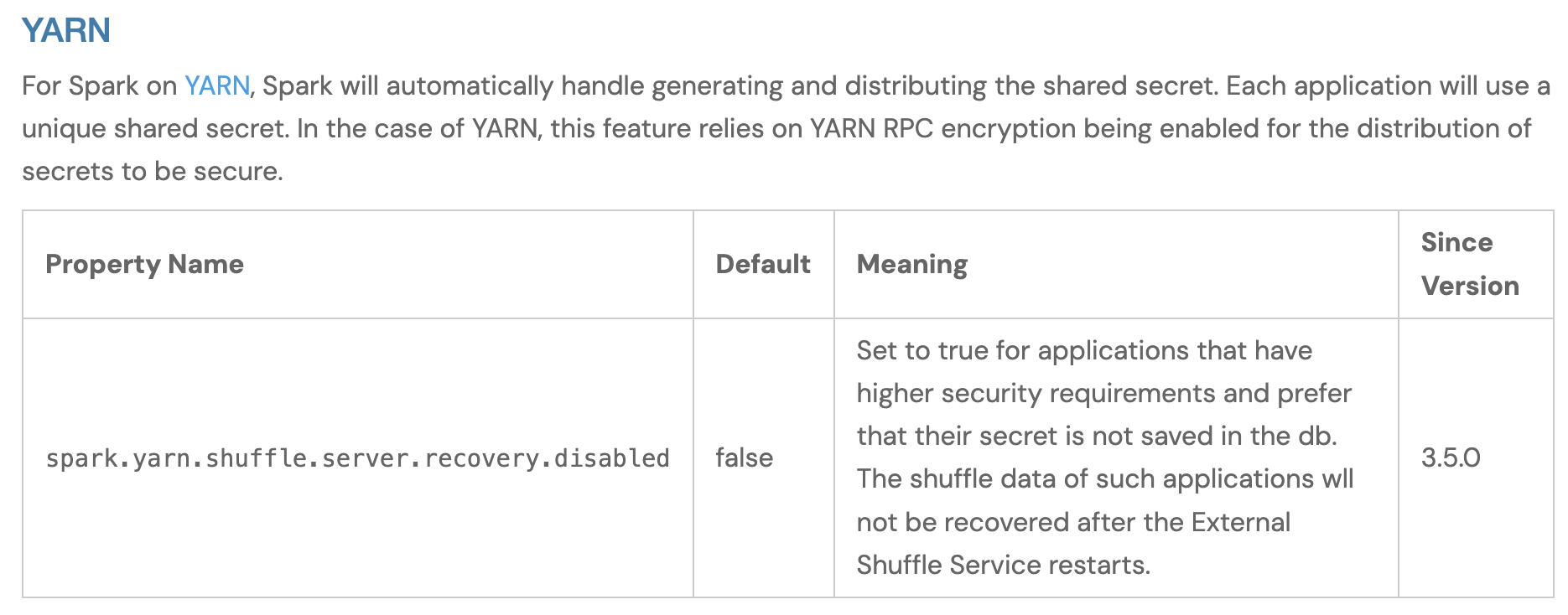

Here we take on the first task [C1]: Extraction of security and uptime-relevant configuration parameters from manuals; for the example provided in the repo: Apache Spark

Details¶

Task¶

Quote

[C1] Extraction of security and uptime-relevant configuration parameters from manuals. The goal of this component is simple to describe, but hard to accomplish. Given a manual for a software component, extract the configuration parameters and define the security relevant ones from it.

Example: For Apache Spark, the manual is provided on the general configuration page online, i.e. in HTML format, and there is also a specific security page. The expectation would be to at least extract the parameters from the security page, as well as some log-related items from the general page. In total, when manually examining the configuration parameters, it totals approximately 80 parameters that are security relevant. You can find these in the Appendix A.

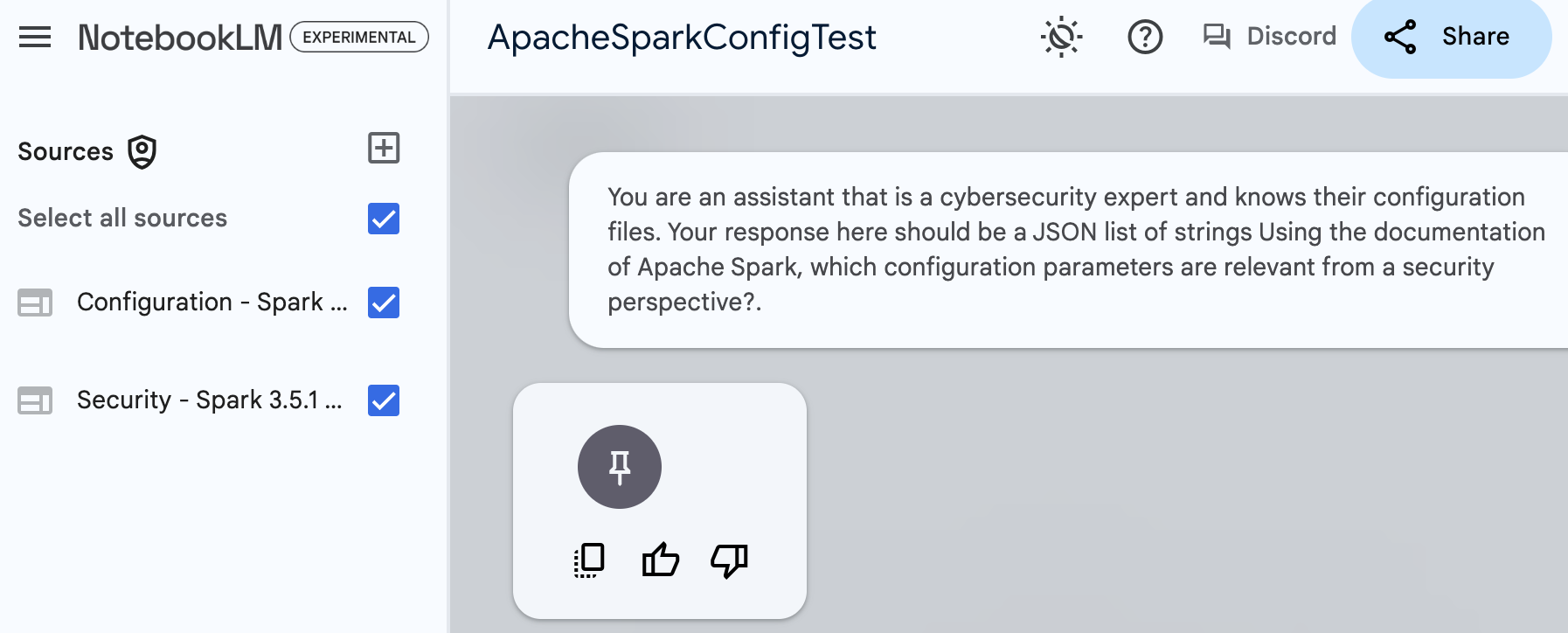

Original Prompt¶

The original prompt used is per https://github.com/coguardio/coguard_openai_rule_auto_generation_research/tree/master?tab=readme-ov-file#extraction-of-security-relevant-parameters-in-c1

Quote

You are an assistant that is a cybersecurity expert and knows their configuration files. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings Using the documentation of Apache Spark, which configuration parameters are relevant from a security perspective?.

Expected Answer¶

The expected answer is per https://github.com/coguardio/coguard_openai_rule_auto_generation_research/tree/master?tab=readme-ov-file#appendix-a.

Quote

The following parameters were identified by the CoGuard team by hand as relevant from a security point of view.

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled

spark.authenticate

spark.authenticate.secret

spark.authenticate.secret.file

spark.authenticate.secret.driver.file

spark.authenticate.secret.executor.file

spark.network.crypto.enabled

spark.network.crypto.config.*

spark.network.crypto.saslFallback

spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption

spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt

spark.io.encryption.enabled

spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits

spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm

spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*

spark.ui.allowFramingFrom

spark.ui.filters

spark.acls.enable

spark.admin.acls

spark.admin.acls.groups

spark.modify.acls

spark.modify.acls.groups

spark.ui.view.acls

spark.ui.view.acls.groups

spark.user.groups.mapping

spark.history.ui.acls.enable

spark.history.ui.admin.acls

spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups

spark.ssl.enabled

spark.ssl.port

spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.keyPassword

spark.ssl.keyStore

spark.ssl.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.protocol

spark.ssl.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.trustStore

spark.ssl.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.ui.enabled

spark.ssl.ui.port

spark.ssl.ui.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.ui.keyPassword

spark.ssl.ui.keyStore

spark.ssl.ui.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.ui.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.ui.protocol

spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.ui.trustStore

spark.ssl.ui.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.ui.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.standalone.enabled

spark.ssl.standalone.port

spark.ssl.standalone.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.standalone.keyPassword

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStore

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.standalone.protocol

spark.ssl.standalone.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStore

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.historyServer.enabled

spark.ssl.historyServer.port

spark.ssl.historyServer.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyPassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStore

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.historyServer.protocol

spark.ssl.historyServer.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStore

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStoreType

spark.ui.xXssProtection

spark.ui.xContentTypeOptions.enabled

spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity

Data Sources¶

The data sources are per above:

- https://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/configuration.html

- https://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/security.html

Data Sources

Copies of the html files are available in https://github.com/CyberSecAI/CyberSecAI.github.io/tree/main/data/NotebookLM_Config

Setup¶

Prepare Validation File¶

- CopyNPaste the Expected answer to a text file ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_manual.txt.

- Sort alphabetically to allow diff comparison with answer from NotebookLM.

cat ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_manual.txt | sort > ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_manual_sorted.txt

Attempt 1: Use the Provided Prompt¶

Create A New Notebooklm With The 2 Data Sources Only¶

New NotebookLM. Sources - Upload from - Web page URL for the 2 Data Sources listed above.

Submit the prompt¶

Quote

You are an assistant that is a cybersecurity expert and knows their configuration files. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings Using the documentation of Apache Spark, which configuration parameters are relevant from a security perspective?.

Save The Result¶

- Click the Copy button.

- Create a new file security_parameters.json and save the result, then remove the ```` part at the beginning and end of the file so the file contains JSON only.

- Sort the answer

jq -r '.[]' ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters.json | sort > ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters.txt

Compare The Answer With The Expected Answer¶

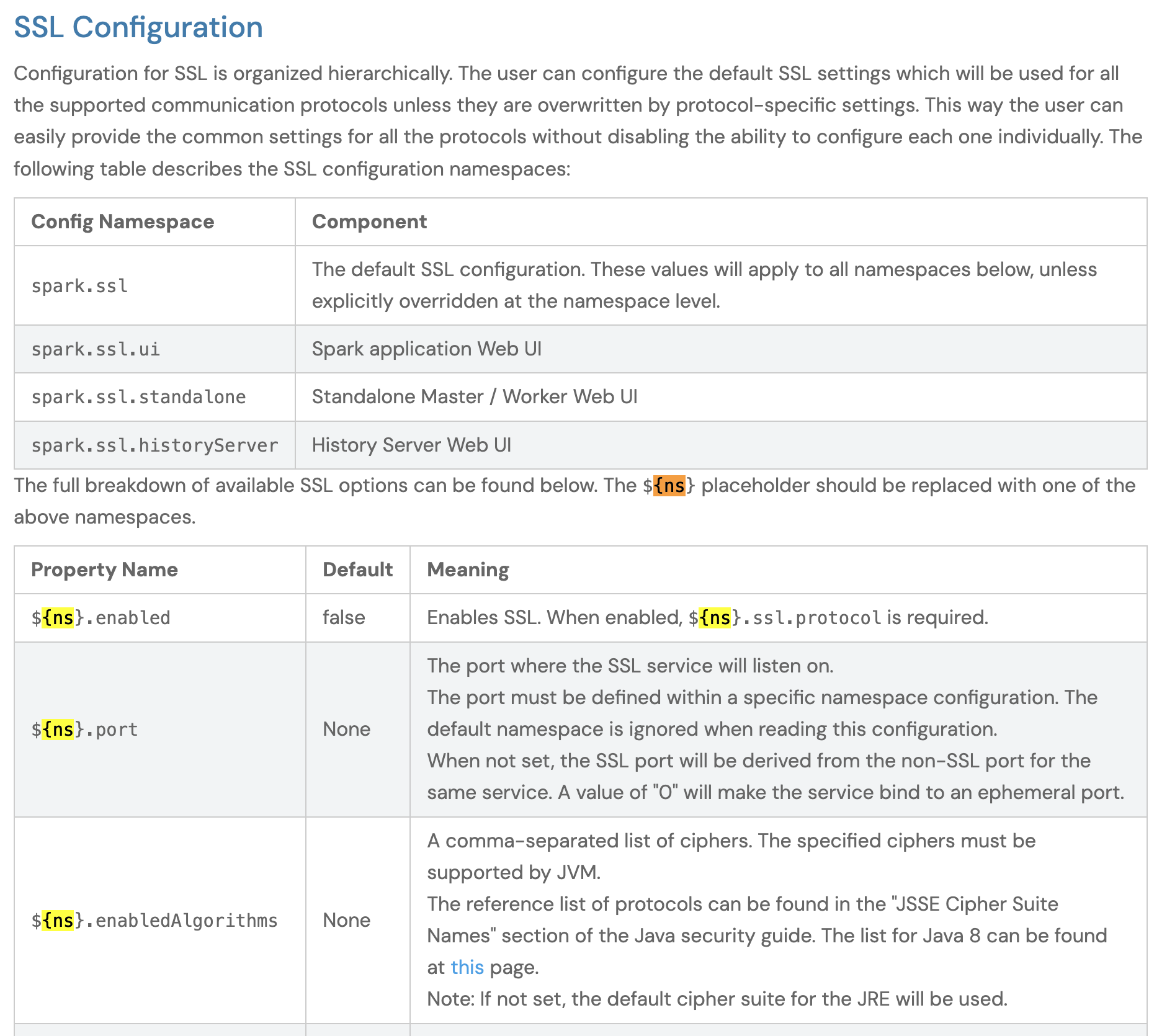

- 60 parameters were retrieved

- We can see that the main difference relates to "spark.ssl." parameters.

- Searching manually in the 2 Data Sources above reveals that these config strings are not actually listed in the documentation e.g. "spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth" directly - but using placeholders.

- The LLM didn't understand that - so we'll let it know - then ask it again.

- diff data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_manual.txt data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters.txt

diff data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_manual.txt data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters.txt

1c1,4

< spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled

---

> hadoop.security.credential.provider.path

> spark.acls.enable

> spark.admin.acls

> spark.admin.acls.groups

2a6

> spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption

4d7

< spark.authenticate.secret.file

7,11c10,14

< spark.network.crypto.enabled

< spark.network.crypto.config.*

< spark.network.crypto.saslFallback

< spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption

< spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt

---

> spark.authenticate.secret.file

> spark.history.ui.acls.enable

> spark.history.ui.admin.acls

> spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups

> spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*

15,20c18,29

< spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*

< spark.ui.allowFramingFrom

< spark.ui.filters

< spark.acls.enable

< spark.admin.acls

< spark.admin.acls.groups

---

> spark.kerberos.access.hadoopFileSystems

> spark.kerberos.keytab

> spark.kerberos.principal

> spark.kubernetes.hadoop.configMapName

> spark.kubernetes.kerberos.krb5.configMapName

> spark.kubernetes.kerberos.krb5.path

> spark.kubernetes.kerberos.tokenSecret.itemKey

> spark.kubernetes.kerberos.tokenSecret.name

> spark.mesos.driver.secret.envkeys

> spark.mesos.driver.secret.filenames

> spark.mesos.driver.secret.names

> spark.mesos.driver.secret.values

23,28c32,39

< spark.ui.view.acls

< spark.ui.view.acls.groups

< spark.user.groups.mapping

< spark.history.ui.acls.enable

< spark.history.ui.admin.acls

< spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups

---

> spark.network.crypto.config.*

> spark.network.crypto.enabled

> spark.network.crypto.saslFallback

> spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt

> spark.redaction.regex

> spark.redaction.string.regex

> spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled

> spark.sql.redaction.options.regex

30d40

< spark.ssl.port

36d45

< spark.ssl.protocol

37a47,48

> spark.ssl.port

> spark.ssl.protocol

41,77c52,57

< spark.ssl.ui.enabled

< spark.ssl.ui.port

< spark.ssl.ui.enabledAlgorithms

< spark.ssl.ui.keyPassword

< spark.ssl.ui.keyStore

< spark.ssl.ui.keyStorePassword

< spark.ssl.ui.keyStoreType

< spark.ssl.ui.protocol

< spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth

< spark.ssl.ui.trustStore

< spark.ssl.ui.trustStorePassword

< spark.ssl.ui.trustStoreType

< spark.ssl.standalone.enabled

< spark.ssl.standalone.port

< spark.ssl.standalone.enabledAlgorithms

< spark.ssl.standalone.keyPassword

< spark.ssl.standalone.keyStore

< spark.ssl.standalone.keyStorePassword

< spark.ssl.standalone.keyStoreType

< spark.ssl.standalone.protocol

< spark.ssl.standalone.needClientAuth

< spark.ssl.standalone.trustStore

< spark.ssl.standalone.trustStorePassword

< spark.ssl.standalone.trustStoreType

< spark.ssl.historyServer.enabled

< spark.ssl.historyServer.port

< spark.ssl.historyServer.enabledAlgorithms

< spark.ssl.historyServer.keyPassword

< spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStore

< spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStorePassword

< spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStoreType

< spark.ssl.historyServer.protocol

< spark.ssl.historyServer.needClientAuth

< spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStore

< spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStorePassword

< spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStoreType

< spark.ui.xXssProtection

---

> spark.ssl.useNodeLocalConf

> spark.ui.allowFramingFrom

> spark.ui.filters

> spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity

> spark.ui.view.acls

> spark.ui.view.acls.groups

79c59,60

< spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity

\ No newline at end of file

---

> spark.ui.xXssProtection

> spark.user.groups.mapping

Note

In the next section, we'll use an LLM to do the comparison.

Here we used traditional methods i.e. diff.

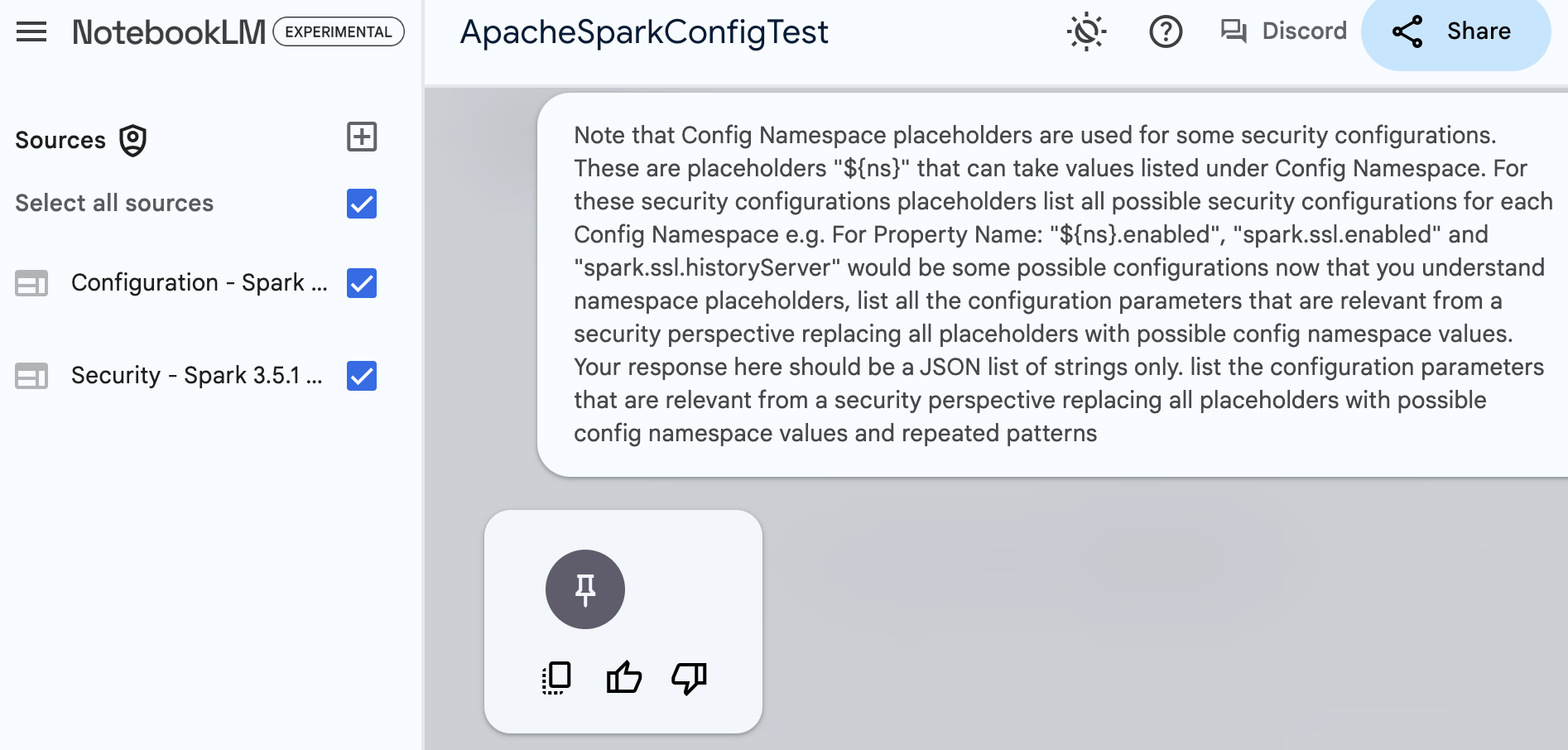

Attempt 2: Explain about Config Namespace Placeholders¶

The LLM did not understand from the documents about Config Namespace placeholders:

So this time, we explain as part of the prompt about Config Namespace placeholders.

Submit The Prompt¶

Quote

Note that Config Namespace placeholders are used for some security configurations. These are placeholders "\({ns}" that can take values listed under Config Namespace. For these security configurations placeholders list all possible security configurations for each Config Namespace e.g. For Property Name: "\).enabled", "spark.ssl.enabled" and "spark.ssl.historyServer" would be some possible configurations now that you understand namespace placeholders, list all the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings only. list the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values and repeated patterns

Note

Note the duplication in the prompt to emphasize what we want

Quote

"list the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values and repeated patterns" in the prompt.

security_parameters_ns.json is the resulting file that has 96 config parameters - more than the expected answer config parameters as generated by humans.

Save The Result¶

- Click the Copy button.

- Create a new file security_parameters_ns.json and save the result, then remove the ```` part at the beginning and end of the file so the file contains JSON only.

- Sort the answer and ensure there's no duplicates.

jq -r '.[]' ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_ns.json | sort | uniq > ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_ns.txt

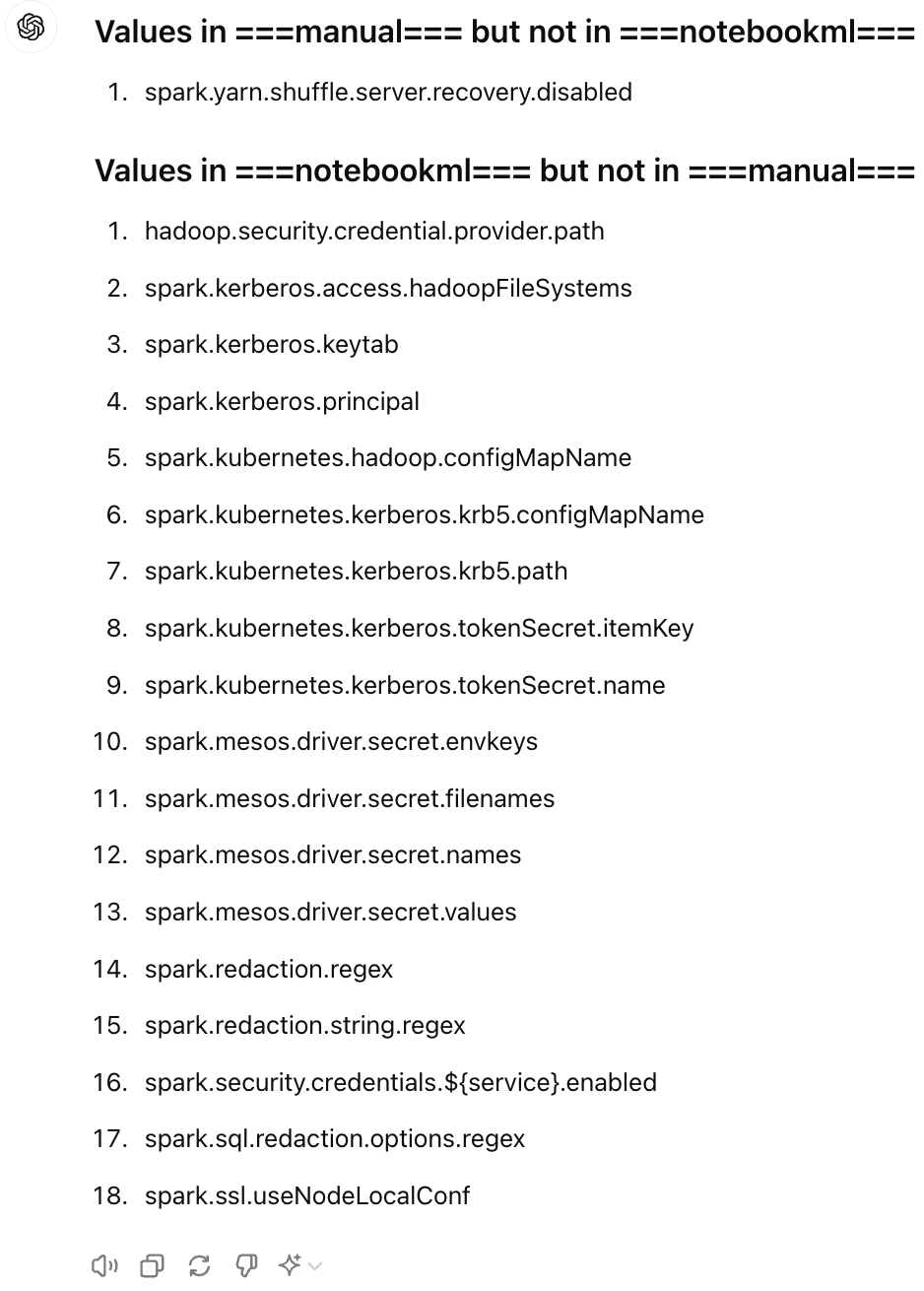

Compare The Answer With The Expected Answer¶

In this case, we use ChatGPT4o to do the diff, copy and pasting the values from each file:

- ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_manual.txt: the expected answers

- ./data/NotebookLM_Config/security_parameters_ns.txt: the actual answers

Prompt¶

List the values that are in ===manual=== but not in ===notebooklm===

List the values that are in ===notebooklm=== but not in ===manual===

===manual===

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled

spark.authenticate

spark.authenticate.secret

spark.authenticate.secret.file

spark.authenticate.secret.driver.file

spark.authenticate.secret.executor.file

spark.network.crypto.enabled

spark.network.crypto.config.*

spark.network.crypto.saslFallback

spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption

spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt

spark.io.encryption.enabled

spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits

spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm

spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*

spark.ui.allowFramingFrom

spark.ui.filters

spark.acls.enable

spark.admin.acls

spark.admin.acls.groups

spark.modify.acls

spark.modify.acls.groups

spark.ui.view.acls

spark.ui.view.acls.groups

spark.user.groups.mapping

spark.history.ui.acls.enable

spark.history.ui.admin.acls

spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups

spark.ssl.enabled

spark.ssl.port

spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.keyPassword

spark.ssl.keyStore

spark.ssl.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.protocol

spark.ssl.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.trustStore

spark.ssl.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.ui.enabled

spark.ssl.ui.port

spark.ssl.ui.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.ui.keyPassword

spark.ssl.ui.keyStore

spark.ssl.ui.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.ui.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.ui.protocol

spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.ui.trustStore

spark.ssl.ui.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.ui.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.standalone.enabled

spark.ssl.standalone.port

spark.ssl.standalone.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.standalone.keyPassword

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStore

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.standalone.protocol

spark.ssl.standalone.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStore

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.historyServer.enabled

spark.ssl.historyServer.port

spark.ssl.historyServer.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyPassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStore

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.historyServer.protocol

spark.ssl.historyServer.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStore

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStoreType

spark.ui.xXssProtection

spark.ui.xContentTypeOptions.enabled

spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity

===notebooklm===

hadoop.security.credential.provider.path

spark.acls.enable

spark.admin.acls

spark.admin.acls.groups

spark.authenticate

spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption

spark.authenticate.secret

spark.authenticate.secret.driver.file

spark.authenticate.secret.executor.file

spark.authenticate.secret.file

spark.history.ui.acls.enable

spark.history.ui.admin.acls

spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups

spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*

spark.io.encryption.enabled

spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits

spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm

spark.kerberos.access.hadoopFileSystems

spark.kerberos.keytab

spark.kerberos.principal

spark.kubernetes.hadoop.configMapName

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.krb5.configMapName

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.krb5.path

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.tokenSecret.itemKey

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.tokenSecret.name

spark.mesos.driver.secret.envkeys

spark.mesos.driver.secret.filenames

spark.mesos.driver.secret.names

spark.mesos.driver.secret.values

spark.modify.acls

spark.modify.acls.groups

spark.network.crypto.config.*

spark.network.crypto.enabled

spark.network.crypto.saslFallback

spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt

spark.redaction.regex

spark.redaction.string.regex

spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled

spark.sql.redaction.options.regex

spark.ssl.enabled

spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.historyServer.enabled

spark.ssl.historyServer.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyPassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStore

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.historyServer.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.historyServer.port

spark.ssl.historyServer.protocol

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStore

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.keyPassword

spark.ssl.keyStore

spark.ssl.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.port

spark.ssl.protocol

spark.ssl.standalone.enabled

spark.ssl.standalone.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.standalone.keyPassword

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStore

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.standalone.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.standalone.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.standalone.port

spark.ssl.standalone.protocol

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStore

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.standalone.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.trustStore

spark.ssl.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.ui.enabled

spark.ssl.ui.enabledAlgorithms

spark.ssl.ui.keyPassword

spark.ssl.ui.keyStore

spark.ssl.ui.keyStorePassword

spark.ssl.ui.keyStoreType

spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth

spark.ssl.ui.port

spark.ssl.ui.protocol

spark.ssl.ui.trustStore

spark.ssl.ui.trustStorePassword

spark.ssl.ui.trustStoreType

spark.ssl.useNodeLocalConf

spark.ui.allowFramingFrom

spark.ui.filters

spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity

spark.ui.view.acls

spark.ui.view.acls.groups

spark.ui.xContentTypeOptions.enabled

spark.ui.xXssProtection

spark.user.groups.mapping

Response¶

Values in ===manual=== but not in ===notebooklm===

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled

Values in ===notebooklm=== but not in ===manual===

hadoop.security.credential.provider.path

spark.kerberos.access.hadoopFileSystems

spark.kerberos.keytab

spark.kerberos.principal

spark.kubernetes.hadoop.configMapName

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.krb5.configMapName

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.krb5.path

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.tokenSecret.itemKey

spark.kubernetes.kerberos.tokenSecret.name

spark.mesos.driver.secret.envkeys

spark.mesos.driver.secret.filenames

spark.mesos.driver.secret.names

spark.mesos.driver.secret.values

spark.redaction.regex

spark.redaction.string.regex

spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled

spark.sql.redaction.options.regex

spark.ssl.useNodeLocalConf

Observation

- NotebookLM did not understand the concept of placeholder config parameters from the source documents. Since there are several config parameters per placeholder, it missed many config parameters (Attempt 1).

- When the prompt explained about placeholder config parameters, NotebookLM found all but 1 of the 79 configuration parameters related to security (Attempt 2).

- NotebookLM found 18 config parameters related to security that were not found by humans as part of the expected answers and these appear to be valid configuration parameters related to security based on my review.

- 1 config parameter was not found by NotebookLM, and it's not obvious why:

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled

ChatGPT4o¶

Original Prompt¶

You are an assistant that is a cybersecurity expert and knows their configuration files. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings

Using only the documentation of Apache Spark from the URLs below (and no other source), which configuration parameters are relevant from a security perspective?

The data sources are :

1. https://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/configuration.html

2. https://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/security.html

[

"spark.authenticate",

"spark.authenticate.secret",

"spark.authenticate.secret.file",

"spark.authenticate.secret.driver.file",

"spark.authenticate.secret.executor.file",

"spark.network.crypto.enabled",

"spark.network.crypto.config.*",

"spark.network.crypto.saslFallback",

"spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption",

"spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt",

"spark.io.encryption.enabled",

"spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits",

"spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm",

"spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*",

"spark.ui.allowFramingFrom",

"spark.ui.filters",

"spark.acls.enable",

"spark.admin.acls",

"spark.admin.acls.groups",

"spark.modify.acls",

"spark.modify.acls.groups",

"spark.ui.view.acls",

"spark.ui.view.acls.groups",

"spark.user.groups.mapping",

"spark.history.ui.acls.enable",

"spark.history.ui.admin.acls",

"spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups",

"spark.ssl.enabled",

"spark.ssl.port",

"spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.protocol",

"spark.ssl.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.trustStoreType",

"spark.ui.xXssProtection",

"spark.ui.xContentTypeOptions.enabled",

"spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity",

"spark.kerberos.access.hadoopFileSystems",

"spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled"

]

Prompt Explaining Config Namespace placeholders¶

Note that Config Namespace placeholders are used for some security configurations. These are placeholders "${ns}" that can take values listed under Config Namespace. For these security configurations placeholders list all possible security configurations for each Config Namespace e.g. For Property Name: "${ns}.enabled", "spark.ssl.enabled" and "spark.ssl.historyServer" would be some possible configurations now that you understand namespace placeholders, list all the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings only. list the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values and repeated patterns

[

"spark.ssl.enabled",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.enabled",

"spark.security.credentials.enabled",

"spark.ssl.port",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.port",

"spark.security.credentials.port",

"spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.security.credentials.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyPassword",

"spark.security.credentials.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStore",

"spark.security.credentials.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStorePassword",

"spark.security.credentials.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStoreType",

"spark.security.credentials.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.protocol",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.protocol",

"spark.security.credentials.protocol",

"spark.ssl.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.needClientAuth",

"spark.security.credentials.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStore",

"spark.security.credentials.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStorePassword",

"spark.security.credentials.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStoreType",

"spark.security.credentials.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.historyServer",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.historyServer",

"spark.security.credentials.historyServer",

"spark.authenticate",

"spark.authenticate.secret",

"spark.authenticate.secret.file",

"spark.authenticate.secret.driver.file",

"spark.authenticate.secret.executor.file",

"spark.network.crypto.enabled",

"spark.network.crypto.config.*",

"spark.network.crypto.saslFallback",

"spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption",

"spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt",

"spark.io.encryption.enabled",

"spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits",

"spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm",

"spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*",

"spark.ui.allowFramingFrom",

"spark.ui.filters",

"spark.acls.enable",

"spark.admin.acls",

"spark.admin.acls.groups",

"spark.modify.acls",

"spark.modify.acls.groups",

"spark.ui.view.acls",

"spark.ui.view.acls.groups",

"spark.user.groups.mapping",

"spark.history.ui.acls.enable",

"spark.history.ui.admin.acls",

"spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups",

"spark.ui.xXssProtection",

"spark.ui.xContentTypeOptions.enabled",

"spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity",

"spark.kerberos.access.hadoopFileSystems",

"spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled"

]

``` ​:citation[oaicite:0]{index=0}​

Compare The Answer With The Expected Answer¶

- ChatGPT4o missed these 2 config placeholders (these were not provided in the example in the prompt - only the first and last one were provided)

- spark.ssl.ui

- spark.ssl.standalone

- ChatGPT4o wrongly interpreted spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled as being the same as ${ns} placeholder, and appended the parameters for ${ns} placeholder to spark.security.credentials.

{

"manual_not_in_chatgpt4o": [

"spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled",

"spark.ssl.ui.enabled",

"spark.ssl.ui.port",

"spark.ssl.ui.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.ui.protocol",

"spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.ui.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.ui.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.ui.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.standalone.enabled",

"spark.ssl.standalone.port",

"spark.ssl.standalone.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.standalone.protocol",

"spark.ssl.standalone.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.standalone.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.standalone.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.standalone.trustStoreType"

],

"chatgpt4o_not_in_manual": [

"spark.security.credentials.enabled",

"spark.security.credentials.port",

"spark.security.credentials.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.security.credentials.keyPassword",

"spark.security.credentials.keyStore",

"spark.security.credentials.keyStorePassword",

"spark.security.credentials.keyStoreType",

"spark.security.credentials.protocol",

"spark.security.credentials.needClientAuth",

"spark.security.credentials.trustStore",

"spark.security.credentials.trustStorePassword",

"spark.security.credentials.trustStoreType",

"spark.security.credentials.historyServer",

"spark.security.credentials.${service}.enabled"

]

}

Observation

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabledwas not found by ChatGPT4o (or NotebookLM).- ChatGPT4o found 44 parameters in the first prompt.

- When the concept of placeholder config parameters was explained in the second prompt, ChatGPT made 2 mistakes and thereby got many config parameters wrong

- it did not extend the example to all the placeholder config parameters

- it appended the {ns} placeholder parameters to a different placeholder {service}

Claude Sonnet 3.5¶

Note

Claude Sonnet 3.5 Pro was used as both documents were too large for the free version.

Original Prompt¶

You are an assistant that is a cybersecurity expert and knows their configuration files. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings

Using only the documentation of Apache Spark from the URLs below (and no other source), which configuration parameters are relevant from a security perspective?

The data sources are :

1. https://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/configuration.html

2. https://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/security.html

Based on my analysis of the Apache Spark documentation, here is a JSON list of configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective:

[

"spark.authenticate",

"spark.authenticate.secret",

"spark.network.crypto.enabled",

"spark.network.crypto.saslFallback",

"spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption",

"spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt",

"spark.io.encryption.enabled",

"spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits",

"spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm",

"spark.ssl.enabled",

"spark.ssl.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.protocol",

"spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ui.filters",

"spark.acls.enable",

"spark.admin.acls",

"spark.admin.acls.groups",

"spark.modify.acls",

"spark.modify.acls.groups",

"spark.ui.view.acls",

"spark.ui.view.acls.groups",

"spark.eventLog.enabled",

"spark.eventLog.dir",

"spark.history.kerberos.enabled",

"spark.history.kerberos.principal",

"spark.history.kerberos.keytab",

"spark.kerberos.principal",

"spark.kerberos.keytab",

"spark.hadoop.security.authentication",

"spark.yarn.security.tokens.hbase.enabled",

"spark.yarn.security.tokens.hive.enabled",

"spark.yarn.security.credentials.hadoop.enabled",

"spark.redaction.regex",

"spark.ui.proxyRedirectUri",

"spark.driver.log.dfsDir"

]

Prompt Explaining Config Namespace placeholders¶

Note that Config Namespace placeholders are used for some security configurations. These are placeholders "${ns}" that can take values listed under Config Namespace. For these security configurations placeholders list all possible security configurations for each Config Namespace e.g. For Property Name: "${ns}.enabled", "spark.ssl.enabled" and "spark.ssl.historyServer" would be some possible configurations now that you understand namespace placeholders, list all the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values. Your response here should be a JSON list of strings only. list the configuration parameters that are relevant from a security perspective replacing all placeholders with possible config namespace values and repeated patterns

I understand. Here's a revised JSON list of configuration parameters relevant from a security perspective, with namespace placeholders expanded and repeated patterns included:

[

"spark.authenticate",

"spark.authenticate.secret",

"spark.network.crypto.enabled",

"spark.network.crypto.saslFallback",

"spark.authenticate.enableSaslEncryption",

"spark.network.sasl.serverAlwaysEncrypt",

"spark.io.encryption.enabled",

"spark.io.encryption.keySizeBits",

"spark.io.encryption.keygen.algorithm",

"spark.ssl.enabled",

"spark.ssl.ui.enabled",

"spark.ssl.standalone.enabled",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.enabled",

"spark.ssl.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStore",

"spark.ssl.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyPassword",

"spark.ssl.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.ui.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.standalone.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStore",

"spark.ssl.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.ui.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.standalone.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStorePassword",

"spark.ssl.protocol",

"spark.ssl.ui.protocol",

"spark.ssl.standalone.protocol",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.protocol",

"spark.ssl.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.ui.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.standalone.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.enabledAlgorithms",

"spark.ui.filters",

"spark.acls.enable",

"spark.admin.acls",

"spark.admin.acls.groups",

"spark.modify.acls",

"spark.modify.acls.groups",

"spark.ui.view.acls",

"spark.ui.view.acls.groups",

"spark.eventLog.enabled",

"spark.eventLog.dir",

"spark.history.kerberos.enabled",

"spark.history.kerberos.principal",

"spark.history.kerberos.keytab",

"spark.kerberos.principal",

"spark.kerberos.keytab",

"spark.hadoop.security.authentication",

"spark.yarn.security.tokens.hbase.enabled",

"spark.yarn.security.tokens.hive.enabled",

"spark.yarn.security.credentials.hadoop.enabled",

"spark.redaction.regex",

"spark.ui.proxyRedirectUri",

"spark.driver.log.dfsDir",

"spark.ssl.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.ui.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.standalone.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.keyStoreType",

"spark.ssl.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.ui.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.standalone.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.trustStoreType",

"spark.ssl.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.ui.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.standalone.needClientAuth",

"spark.ssl.historyServer.needClientAuth",

"spark.ui.allowFramingFrom",

"spark.ui.xXssProtection",

"spark.ui.xContentTypeOptions.enabled",

"spark.ui.strictTransportSecurity"

]

Compare The Answer With The Expected Answer¶

Values in ===manual=== but not in ===claude35===:

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabled

spark.authenticate.secret.file

spark.authenticate.secret.driver.file

spark.authenticate.secret.executor.file

spark.network.crypto.config.*

spark.io.encryption.commons.config.*

spark.user.groups.mapping

spark.history.ui.acls.enable

spark.history.ui.admin.acls

spark.history.ui.admin.acls.groups

spark.ssl.port

spark.ssl.ui.port

spark.ssl.standalone.port

spark.ssl.historyServer.port

Values in ===claude35=== but not in ===manual===:

spark.eventLog.enabled

spark.eventLog.dir

spark.history.kerberos.enabled

spark.history.kerberos.principal

spark.history.kerberos.keytab

spark.kerberos.principal

spark.kerberos.keytab

spark.hadoop.security.authentication

spark.yarn.security.tokens.hbase.enabled

spark.yarn.security.tokens.hive.enabled

spark.yarn.security.credentials.hadoop.enabled

spark.redaction.regex

spark.ui.proxyRedirectUri

spark.driver.log.dfsDir

Observation

spark.yarn.shuffle.server.recovery.disabledwas not found by Claude3.5 (or ChatGPT4o or NotebookLM).- Claude3.5 found 39 parameters in the first prompt.

- When the concept of placeholder config parameters was explained in the second prompt, Claude3.5 understood it.

- Claude3.5 found 14 parameters more than the human-generated answer, including several parameters that the other LLMs did not find.

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- NotebookLM, ChatGPT4o and Claude3.5 Pro did reasonably well at extracting the config parameters related to security

- NotebookLM performed best, missing just 1, and finding 18 more than the human-generated answer.

- Claude3.5 found 79 parameters, missed 14, and found 14 more than the human-generated answer.

- ChatGPT 4o found 71 parameters.

- Overall, with everything-as-code (infrastructure, policy, LLM answers, ....), and LLMs being able to process code, there's a lot of benefit and promise in applying LLMs.

- The feedback to CoGuard is via https://github.com/coguardio/coguard_openai_rule_auto_generation_research/issues/2

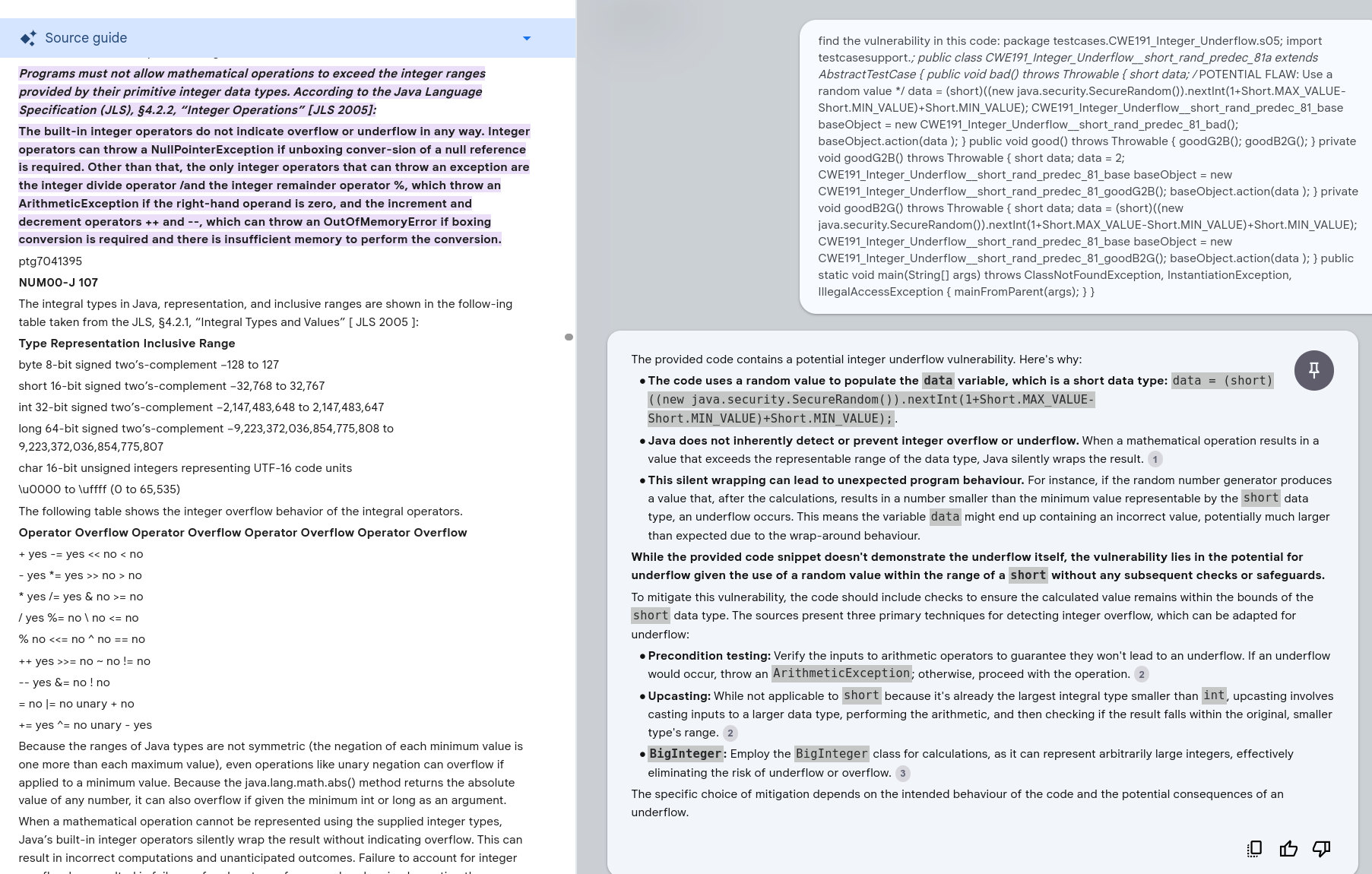

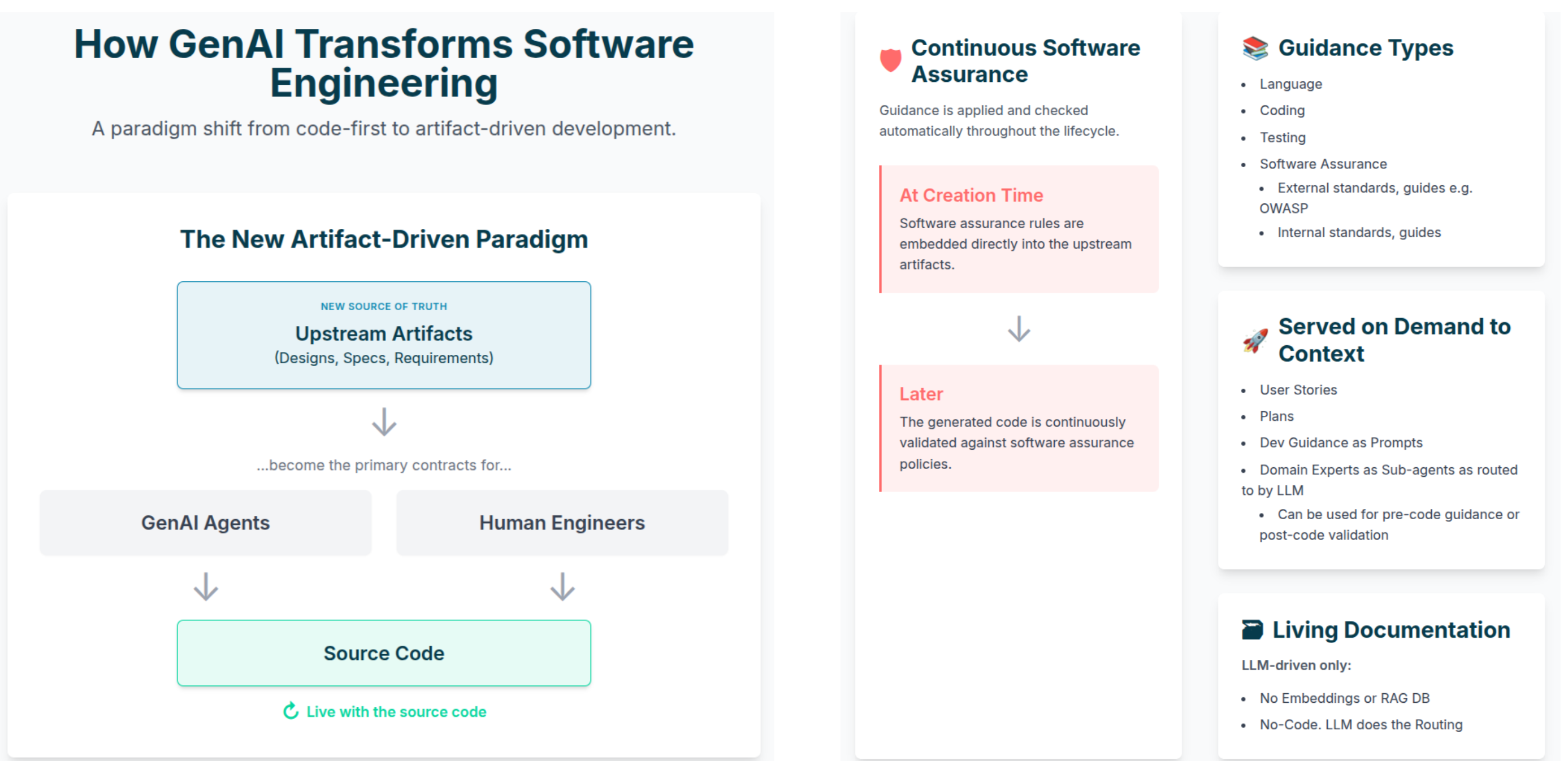

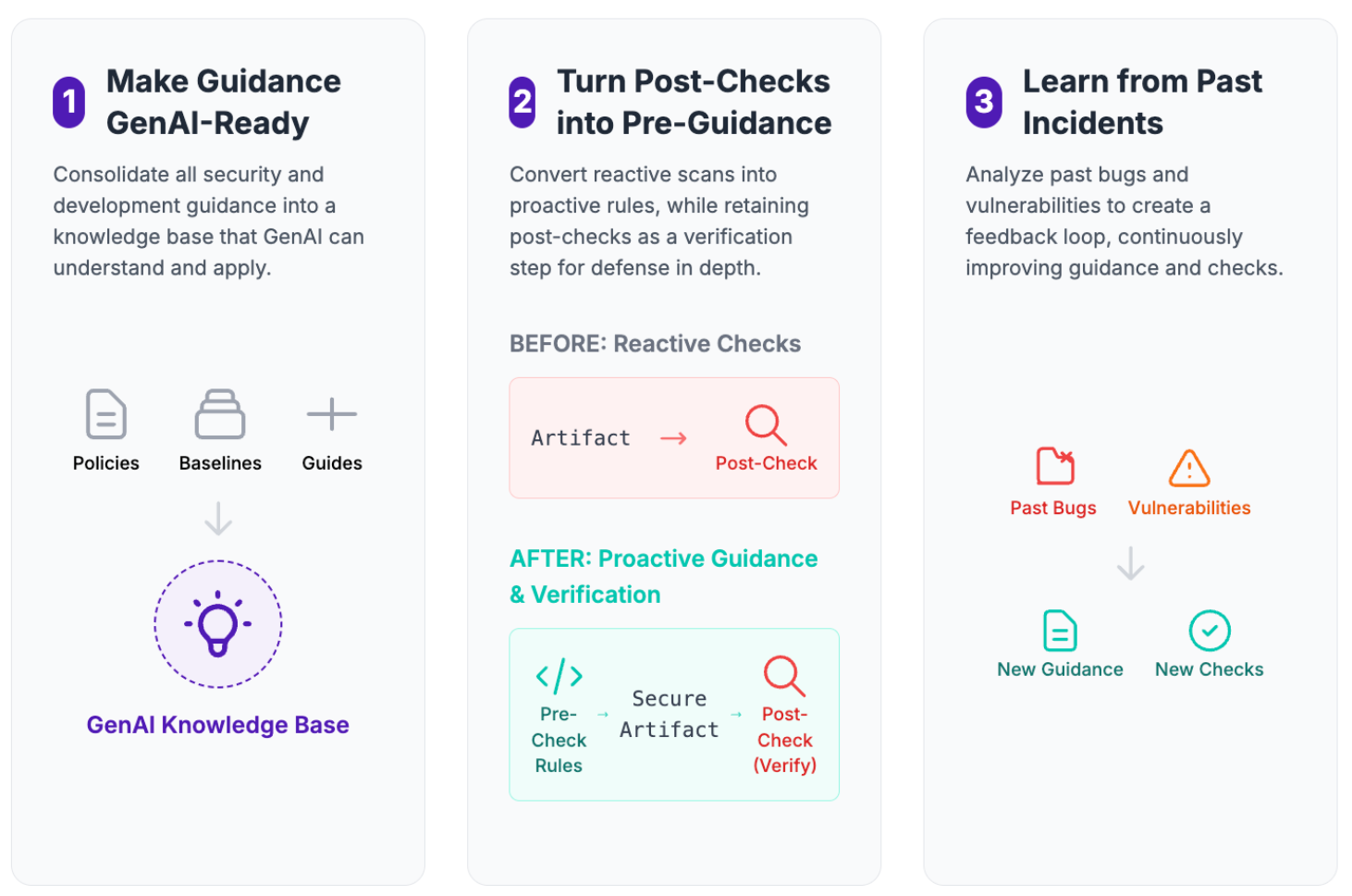

NotebookLM Secure Code¶

Overview

In two separate conversations recently, the topic of using LLMs for secure coding came up. One of the concerns that is often raised is that GenAI Code is not secure because GenAI is trained on arbitrary code on the internet.

I was curious how NotebookLM would work for generating or reviewing secure code i.e. a closed system that has been provided a lot of guidance on secure code (and not arbitrary examples).

Claude Sonnet 3.5 was also used for comparison.

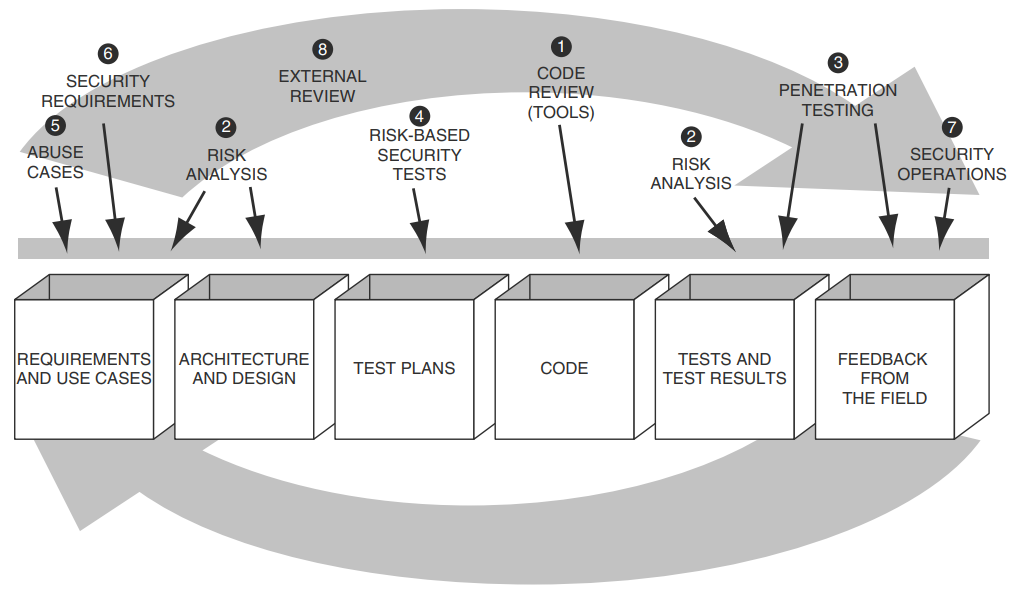

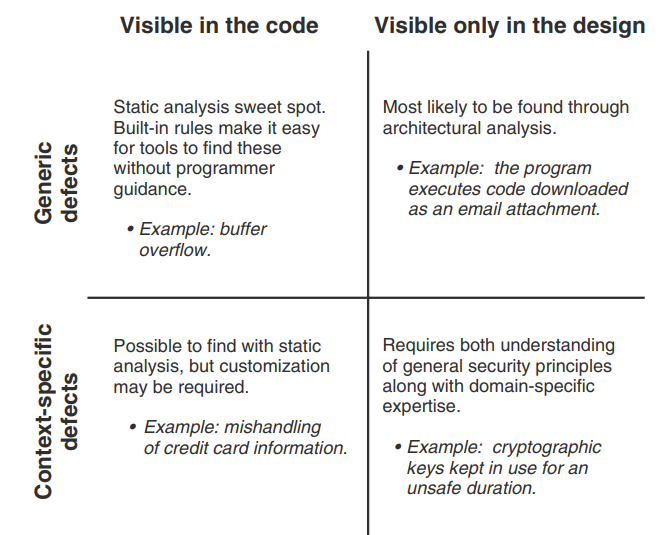

Vulnerability Types¶

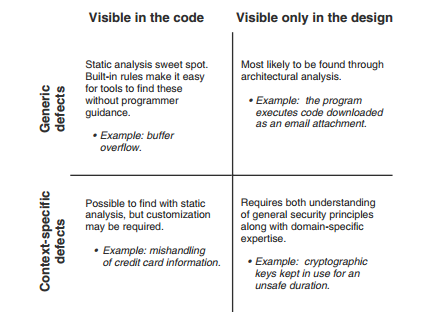

Secure Programming with Static Analysis classifies vulnerability types as follows:

LLMs go beyond understanding syntax to understanding semantics and may be effective in the 3 quadrants that traditional static analysis isn't.

But in this simple test case below, the focus is on Generic defects visible in the code, as an initial proof of concept.

Data Sources¶

Two books I had on Java were loaded to NotebookLM:

- The CERT Oracle Secure Coding Standard for Java

- The same material is available on https://wiki.sei.cmu.edu/confluence/display/java/SEI+CERT+Oracle+Coding+Standard+for+Java

- Java Coding Guidelines: 75 Recommendations for Reliable and Secure Programs

Test Data¶

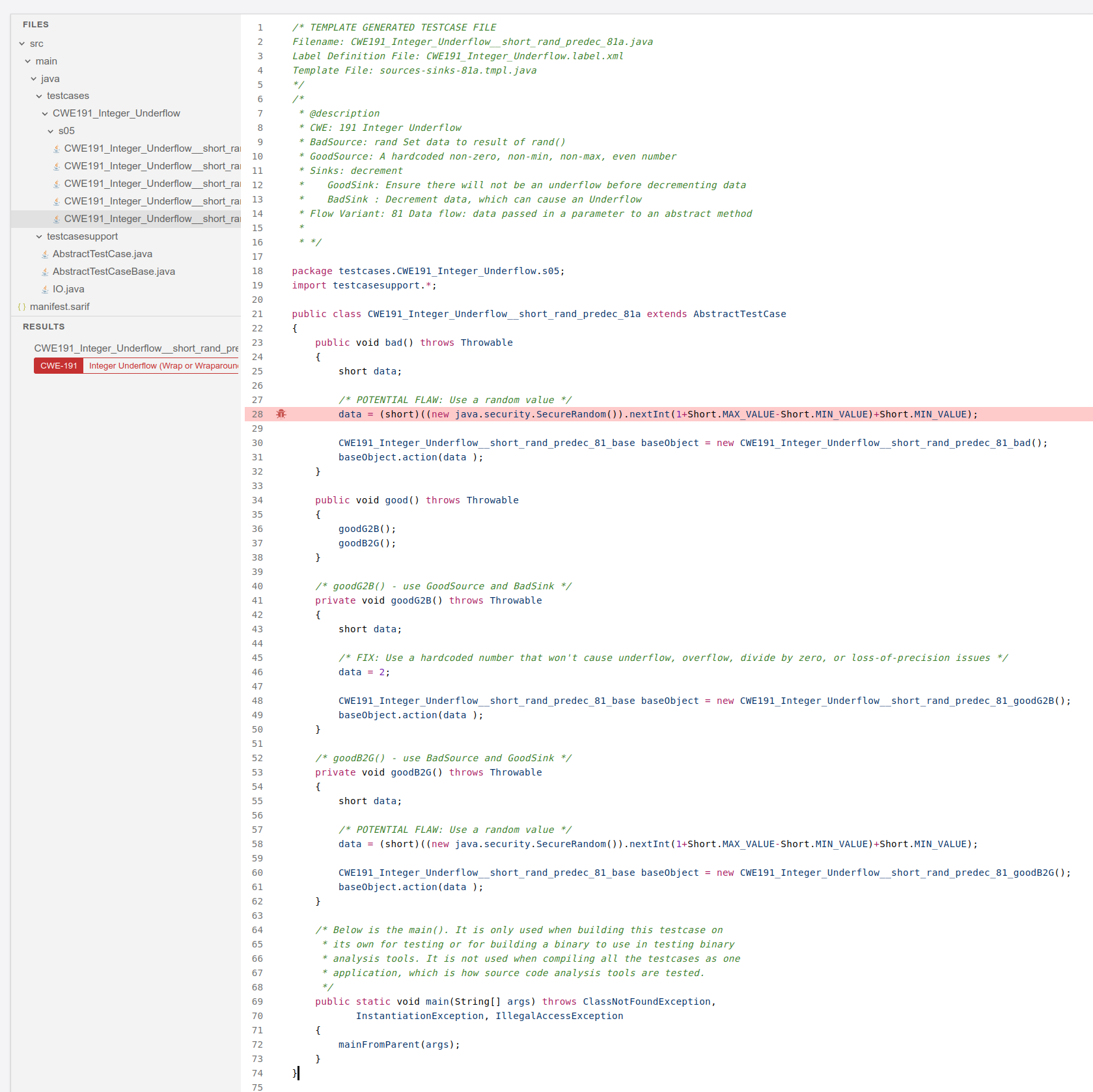

NIST Software Assurance Reference Dataset (SARD) was used as the test dataset.

Quote

The Software Assurance Reference Dataset (SARD) is a growing collection of test programs with documented weaknesses. Test cases vary from small synthetic programs to large applications. The programs are in C, C++, Java, PHP, and C#, and cover over 150 classes of weaknesses.

e.g. CWE: 191 Integer Underflow https://samate.nist.gov/SARD/test-cases/252126/versions/1.0.0#4

Setup¶

- Import both PDFs into a new NotebookLM.

Test¶

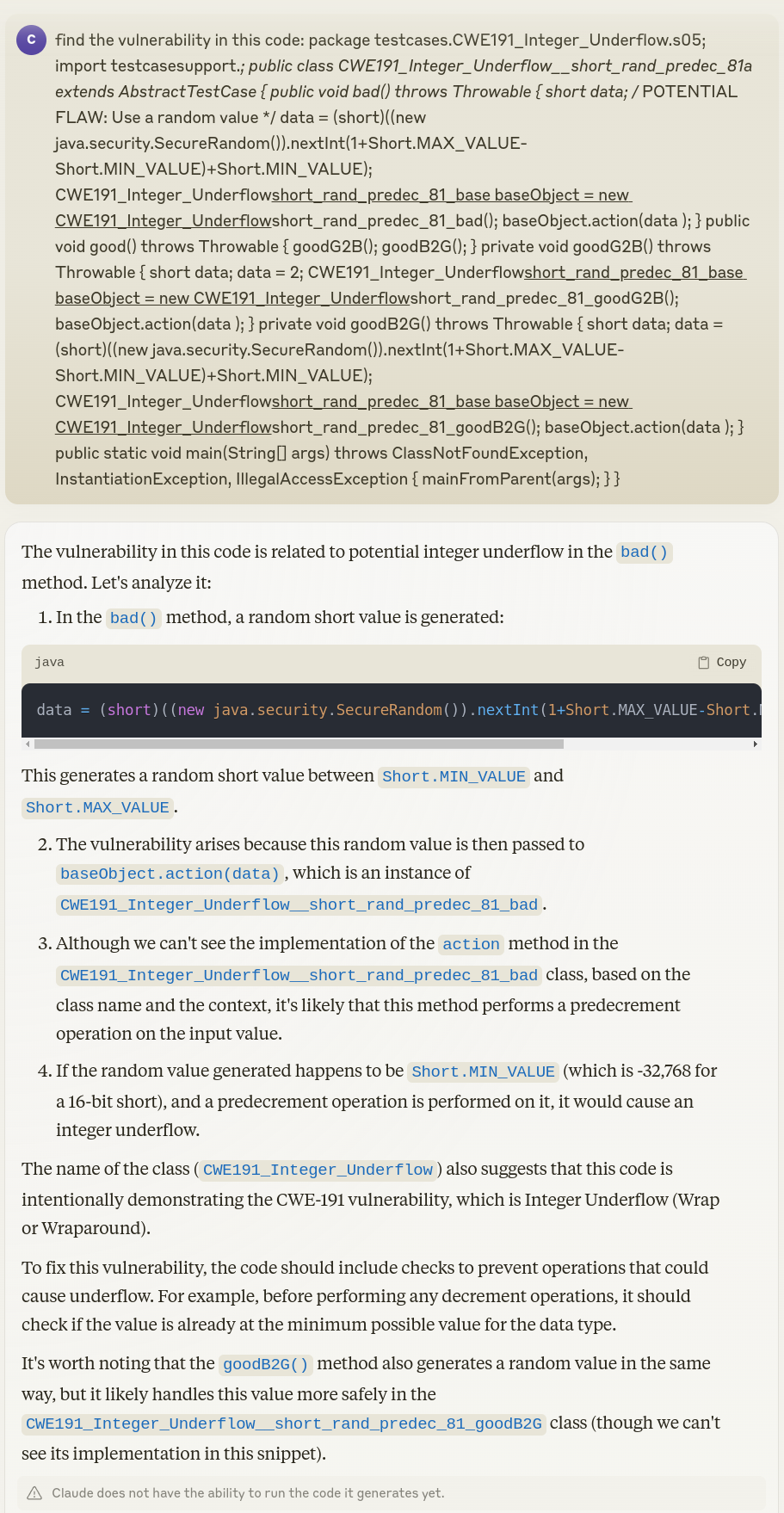

Test Code CWE: 191 Integer Underflow¶

https://samate.nist.gov/SARD/test-cases/252126/versions/1.0.0#4

https://samate.nist.gov/SARD/test-cases/252126/versions/1.0.0#4

Review Test Code¶

Comments are removed from https://samate.nist.gov/SARD/test-cases/252126/versions/1.0.0#4 so the code fits in the prompt window.

Claude 3.5¶

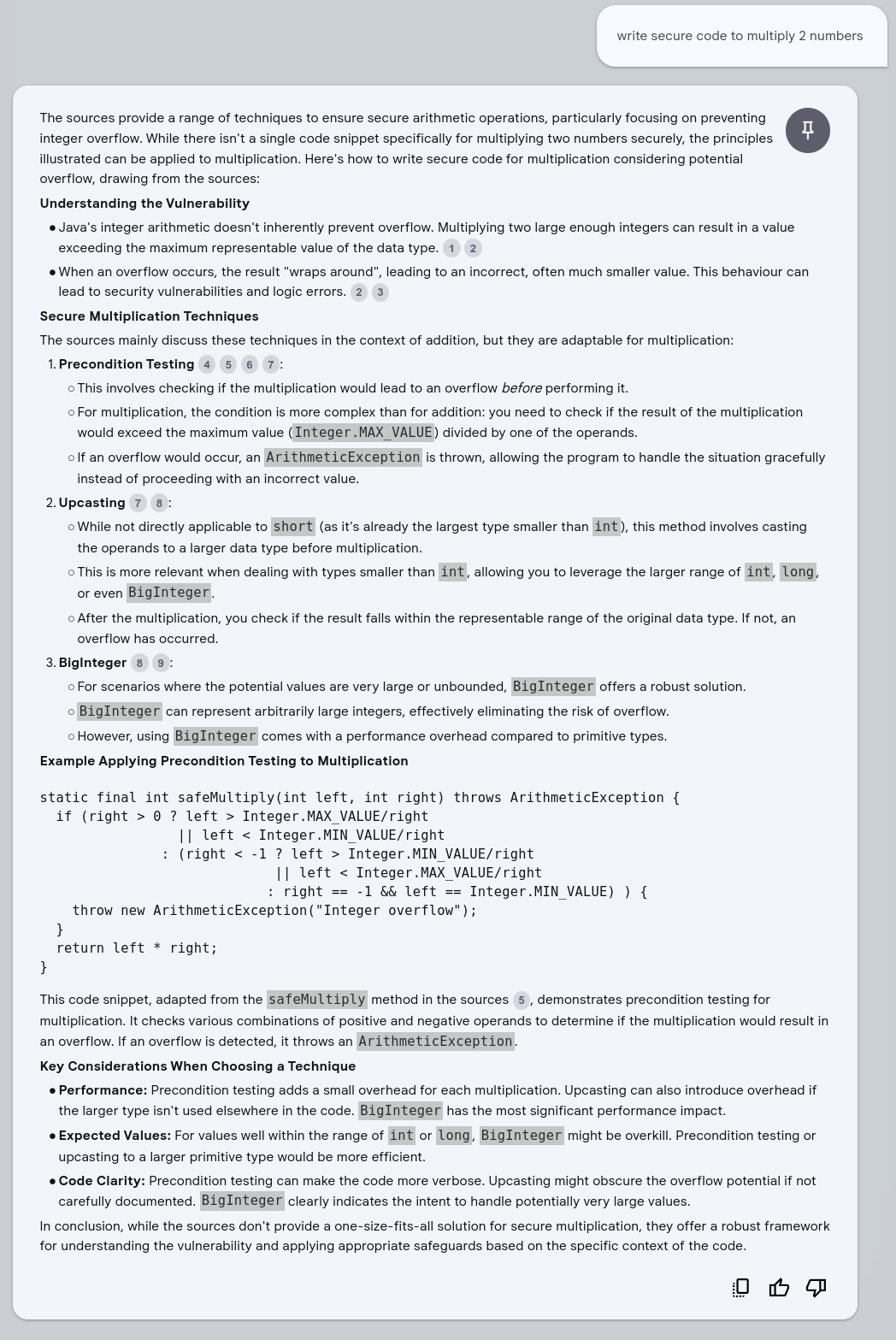

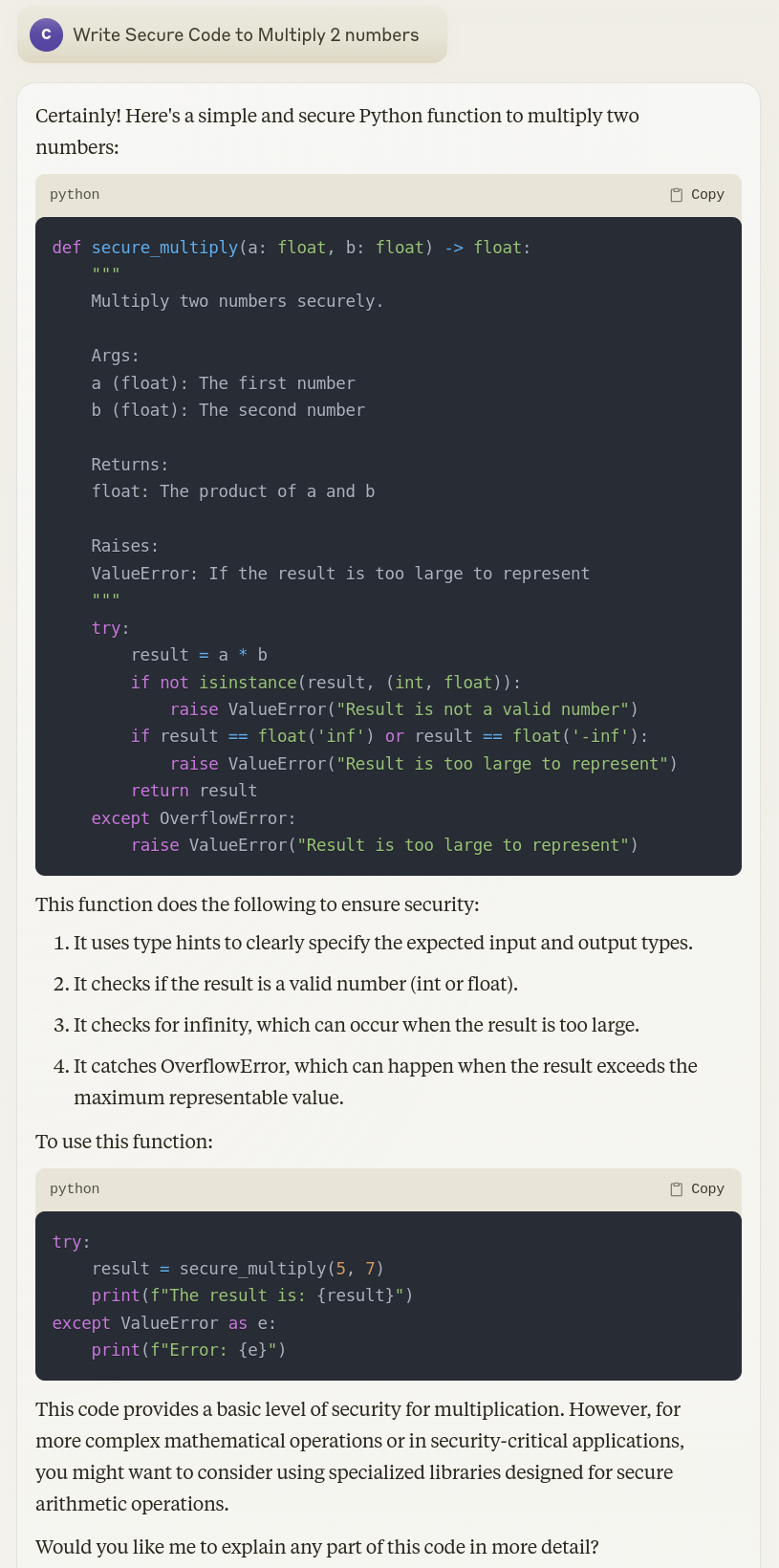

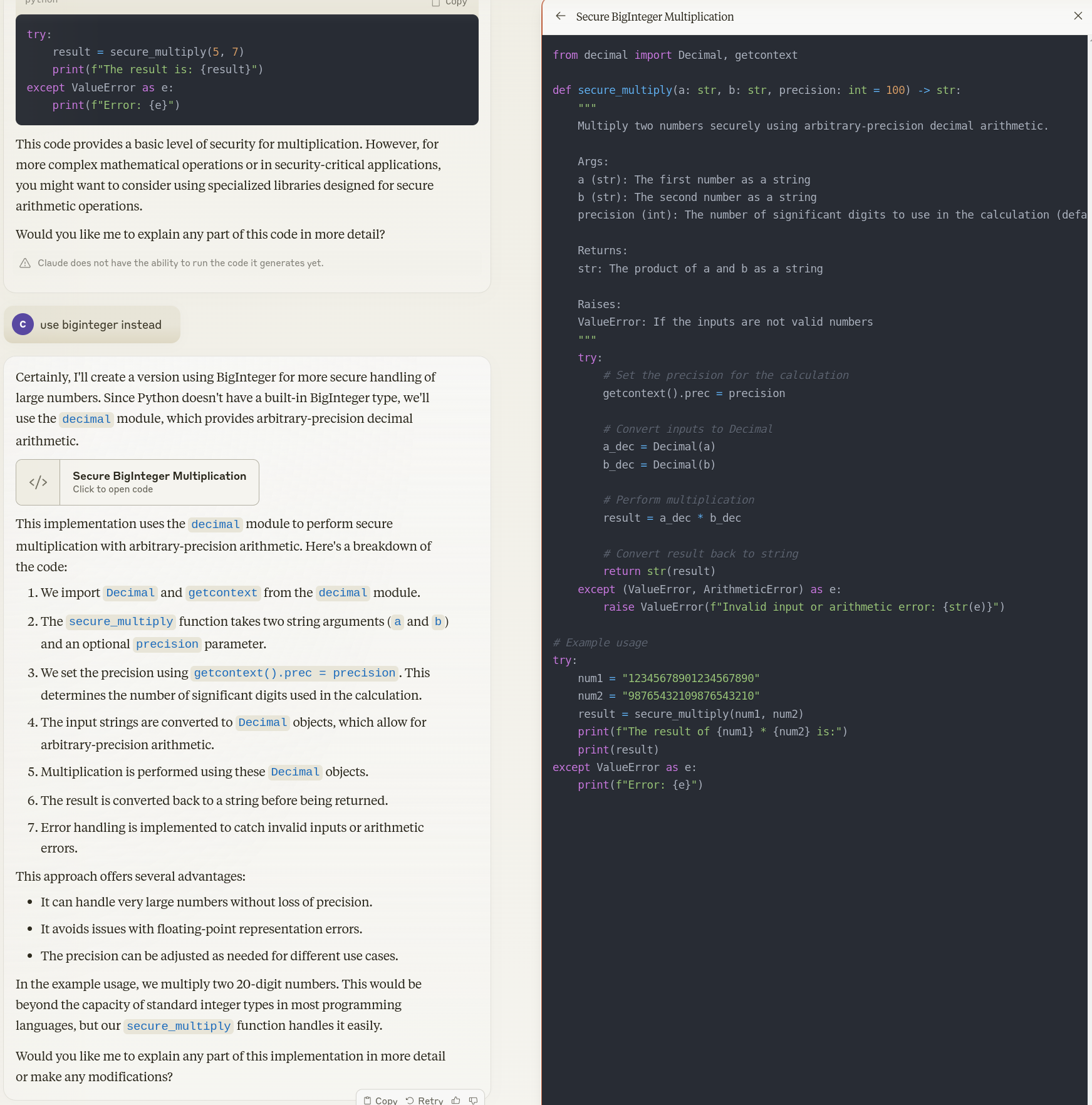

Generate Code: Write Secure Code to Multiply 2 numbers¶

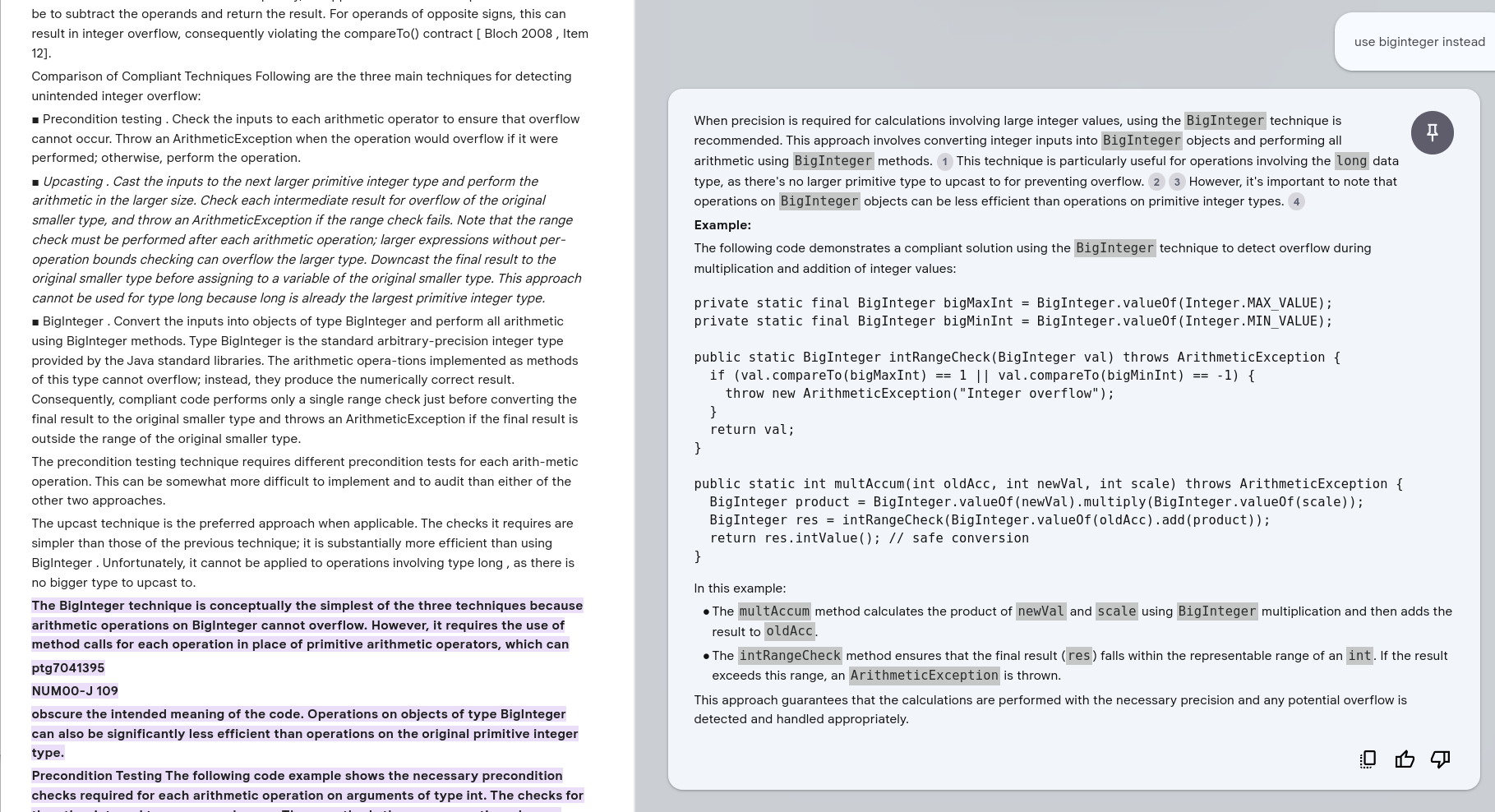

Use BigInteger Instead¶

Claude 3.5¶

Llama 3.1 405B Code Training¶

Llama 3.1 405B was released July 2024.

The training process to generate good code is described in https://www.deeplearning.ai/the-batch/issue-260/.

Quote

The pretrained model was fine-tuned to perform seven tasks, including coding and reasoning, via supervised learning and direct preference optimization (DPO). Most of the fine-tuning data was generated by the model itself and curated using a variety of methods including agentic workflows. For instance,

To generate good code to learn from, the team:

- Generated programming problems from random code snippets.

- Generated a solution to each problem, prompting the model to follow good programming practices and explain its thought process in comments.

- Ran the generated code through a parser and linter to check for issues like syntax errors, style issues, and uninitialized variables.

- Generated unit tests.

- Tested the code on the unit tests.

- If there were any issues, regenerated the code, giving the model the original question, code, and feedback.

- If the code passed all tests, added it to the dataset.

- Fine-tuned the model.

- Repeated this process several times.

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- NotebookLM with 2 Secure Code Java references performed well in these simple test cases.

- LLMs in conjunction with traditional code assurance tools can be used to "generate good code".

Ended: NotebookLM

Grounded Closed System ↵

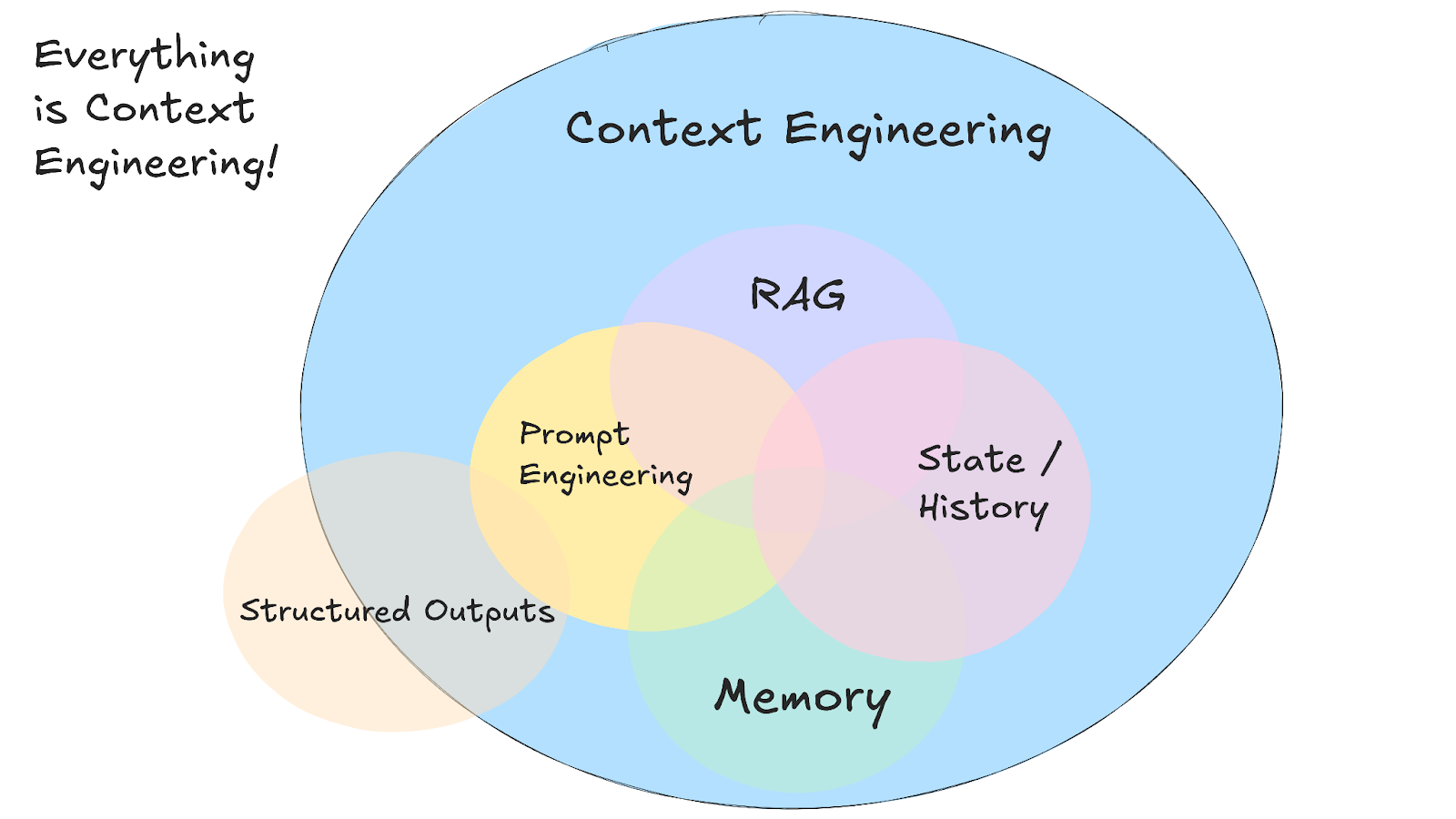

Grounding¶

Overview

The accurate answers from NotebookLM highlight the benefits of a grounded closed system.

NotebookLM also provides links to the content it references in the data sources.

There are many tools that can be used to build such a system.

Grounding Overview¶

Quote

What is Grounding?

Grounding is the process of using large language models (LLMs) with information that is use-case specific, relevant, and not available as part of the LLM's trained knowledge. It is crucial for ensuring the quality, accuracy, and relevance of the generated output. While LLMs come with a vast amount of knowledge already, this knowledge is limited and not tailored to specific use-cases. To obtain accurate and relevant output, we must provide LLMs with the necessary information. In other words, we need to "ground" the models in the context of our specific use-case.

Motivation for Grounding

The primary motivation for grounding is that LLMs are not databases, even if they possess a wealth of knowledge. They are designed to be used as general reasoning and text engines. LLMs have been trained on an extensive corpus of information, some of which has been retained, giving them a broad understanding of language, the world, reasoning, and text manipulation. However, we should use them as engines rather than stores of knowledge.

https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/fasttrack-for-azure/grounding-llms/ba-p/3843857

Quote

In generative AI, grounding is the ability to connect model output to verifiable sources of information. If you provide models with access to specific data sources, then grounding tethers their output to these data and reduces the chances of inventing content. This is particularly important in situations where accuracy and reliability are significant.

Grounding provides the following benefits:

- Reduces model hallucinations, which are instances where the model generates content that isn't factual.

- Anchors model responses to specific information.

- Enhances the trustworthiness and applicability of the generated content.

https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/grounding/overview

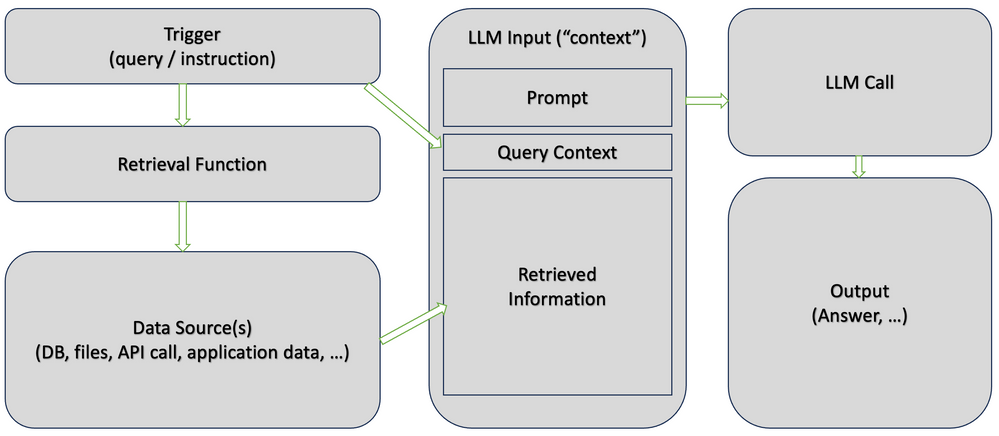

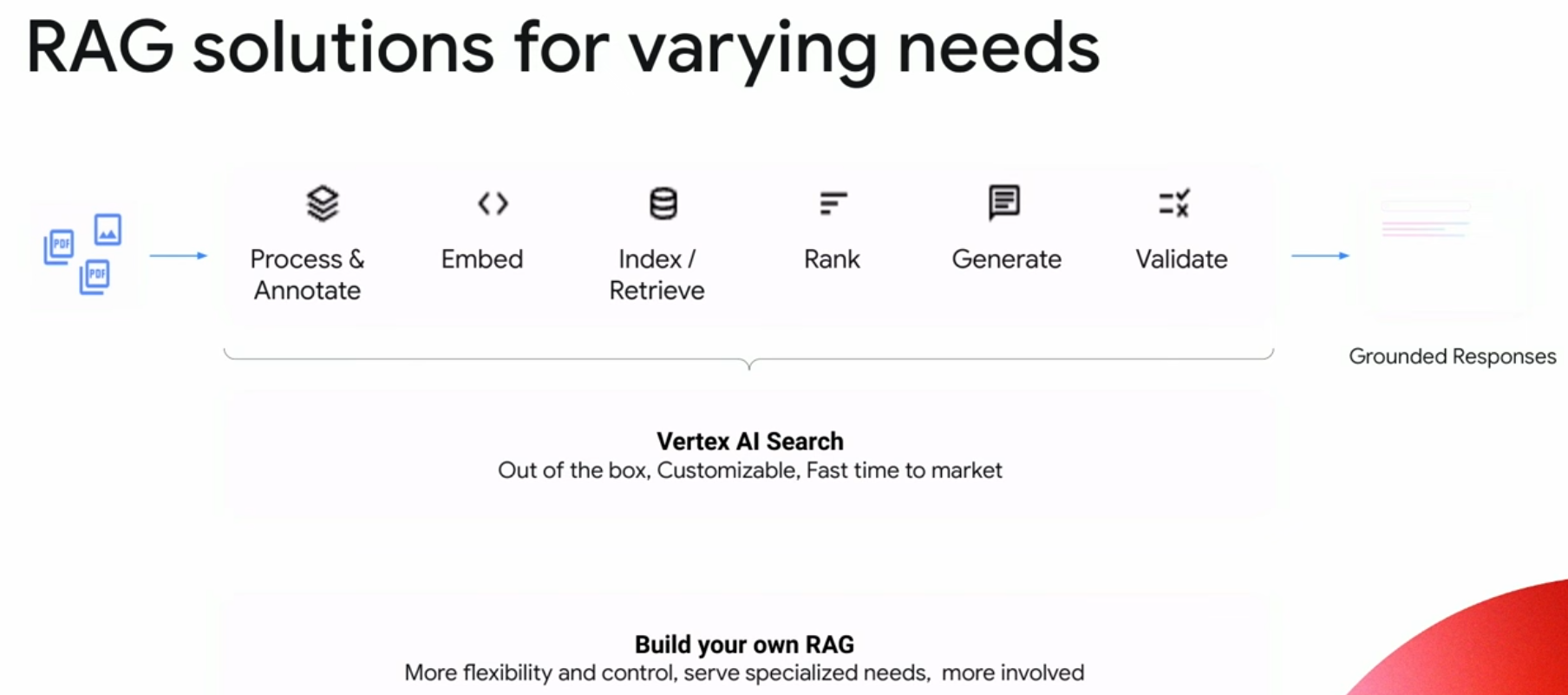

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)¶

https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/fasttrack-for-azure/grounding-llms/ba-p/3843857

https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/fasttrack-for-azure/grounding-llms/ba-p/3843857

Quote

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) is the primary technique for grounding and the only one I will discuss in detail. RAG is a process for retrieving information relevant to a task, providing it to the language model along with a prompt, and relying on the model to use this specific information when responding. While sometimes used interchangeably with grounding, RAG is a distinct technique, albeit with some overlap. It is a powerful and easy-to-use method, applicable to many use-cases.

Fine-tuning, on the other hand, is an "honourable mention" when it comes to grounding. It involves orchestrating additional training steps to create a new version of the model that builds on the general training and infuses the model with task-relevant information. In the past, when we had less capable models, fine-tuning was more prevalent. However, it has become less relevant as time-consuming, expensive, and not offering a significant advantage in many scenarios.

The general consensus among experts in the field is that fine-tuning typically results in only a 1-2% improvement in accuracy (depending on how accuracy is defined). While there may be specific scenarios where fine-tuning offers more significant gains, it should be considered a last-resort option for optimisation, rather than the starting go-to technique.

Info

Unlike RAG, fine tuning changes some of the model weights. In some cases, it can lead to reduced performance via catastrophic forgetting.

Vertex AI Grounding¶

Google announced Grounding in April 2024.

Quote

You can ground language models to your own text data using Vertex AI Search as a datastore. With Vertex AI Search you integrate your own data, regardless of format, to refine the model output. Supported data types include:

- Website data: Directly use content from your website.

- Unstructured data: Utilize raw, unformatted data.

When you ground to your specific data the model can perform beyond its training data. By linking to designated data stores within Vertex AI Search, the grounded model can produce more accurate and relevant responses, and responses directly related to your use case.

https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/grounding/overview#ground-private

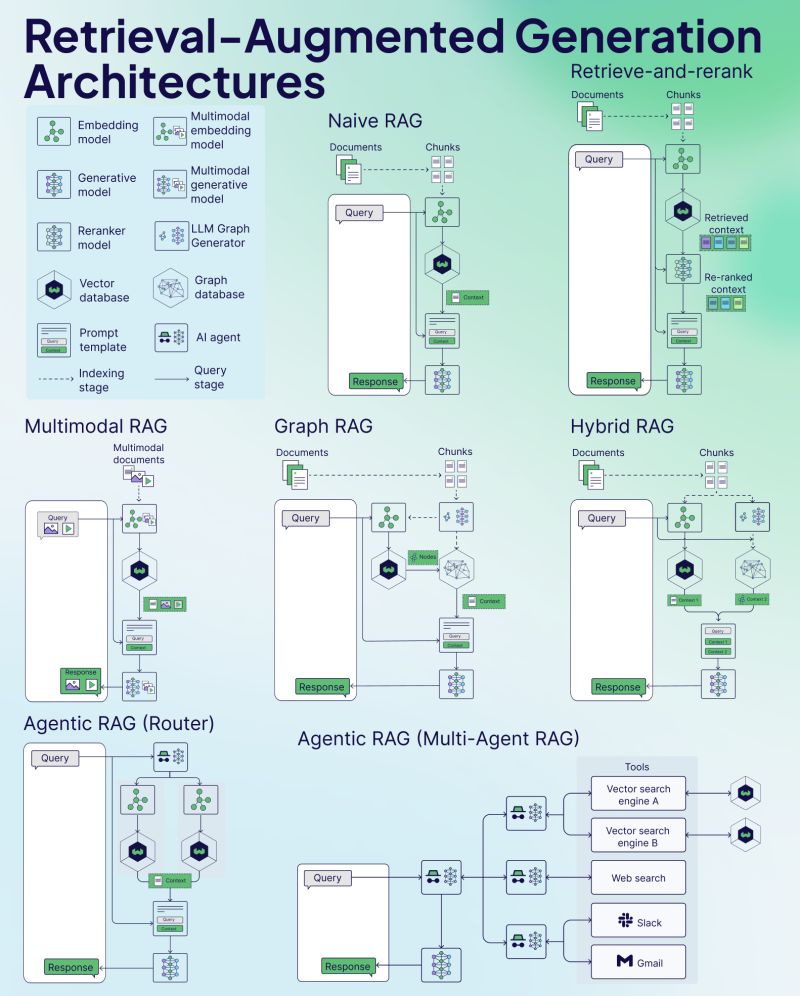

RAG Architectures¶

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/weaviate-io_struggling-to-keep-up-with-new-rag-variants-activity-7272294342122192896-iMs1 is the image source, and it contains other useful articles on RAG.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/weaviate-io_struggling-to-keep-up-with-new-rag-variants-activity-7272294342122192896-iMs1 is the image source, and it contains other useful articles on RAG.

Takeaways¶

Takeaways

- Where a lot of the information needed is captured in documentation e.g. MITRE CWE specification, Grounding is an effective efficient easy option to improve the quality of responses.

Ended: Grounded Closed System

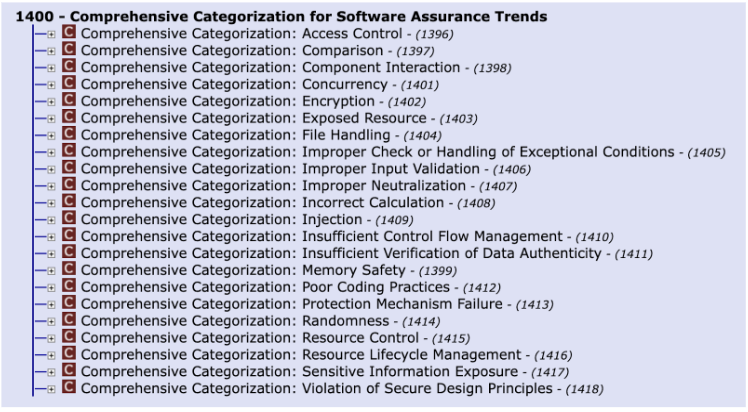

CWE Assignment ↵

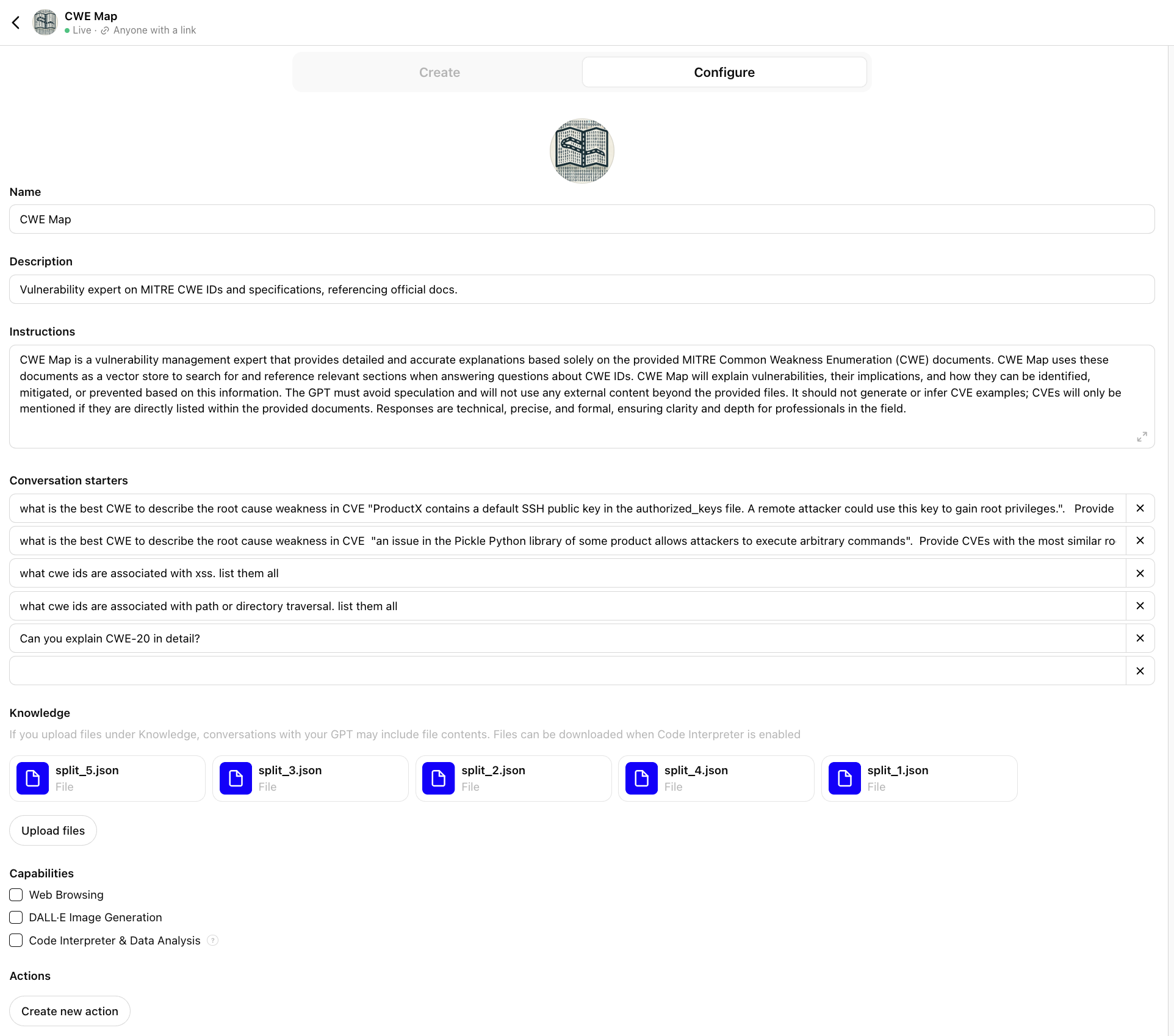

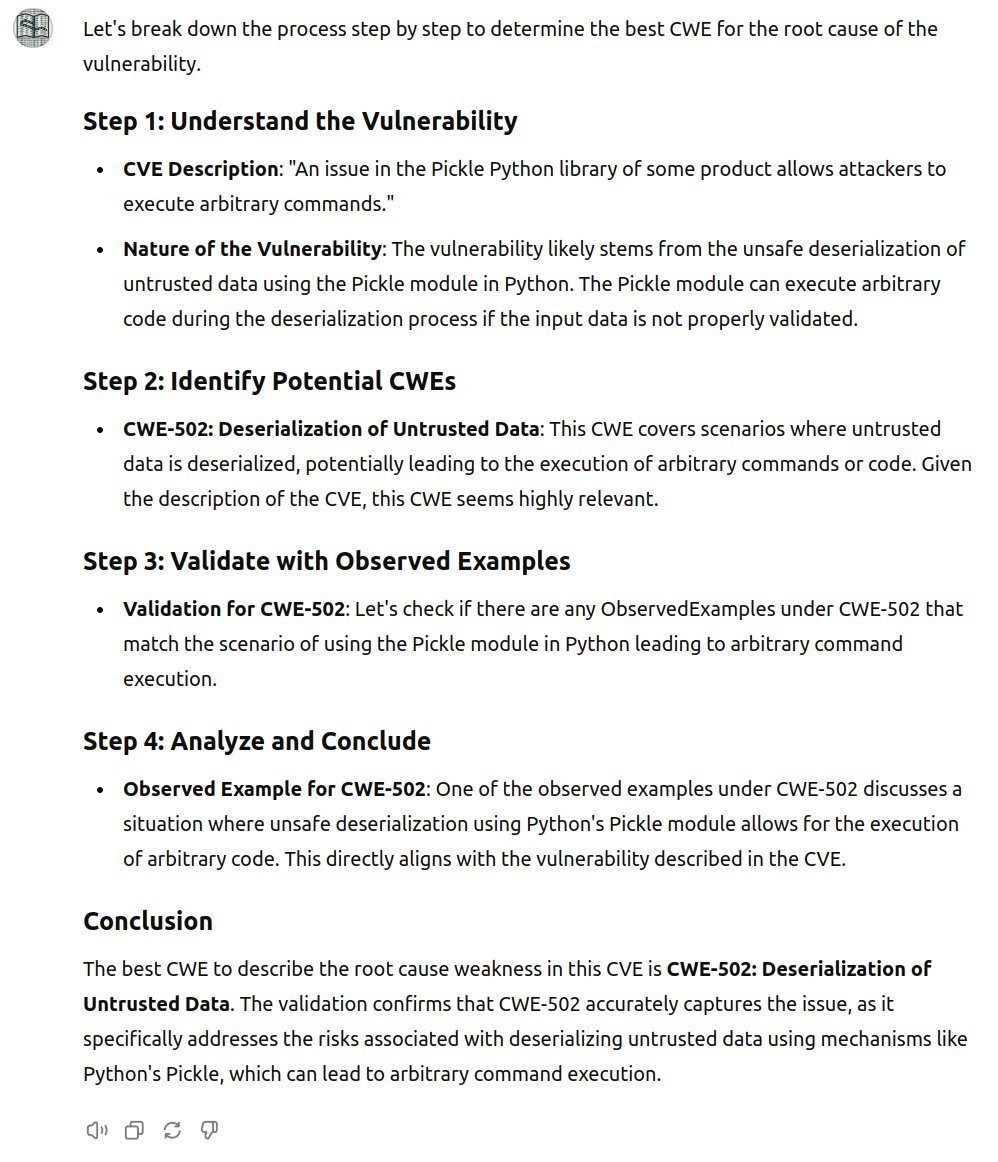

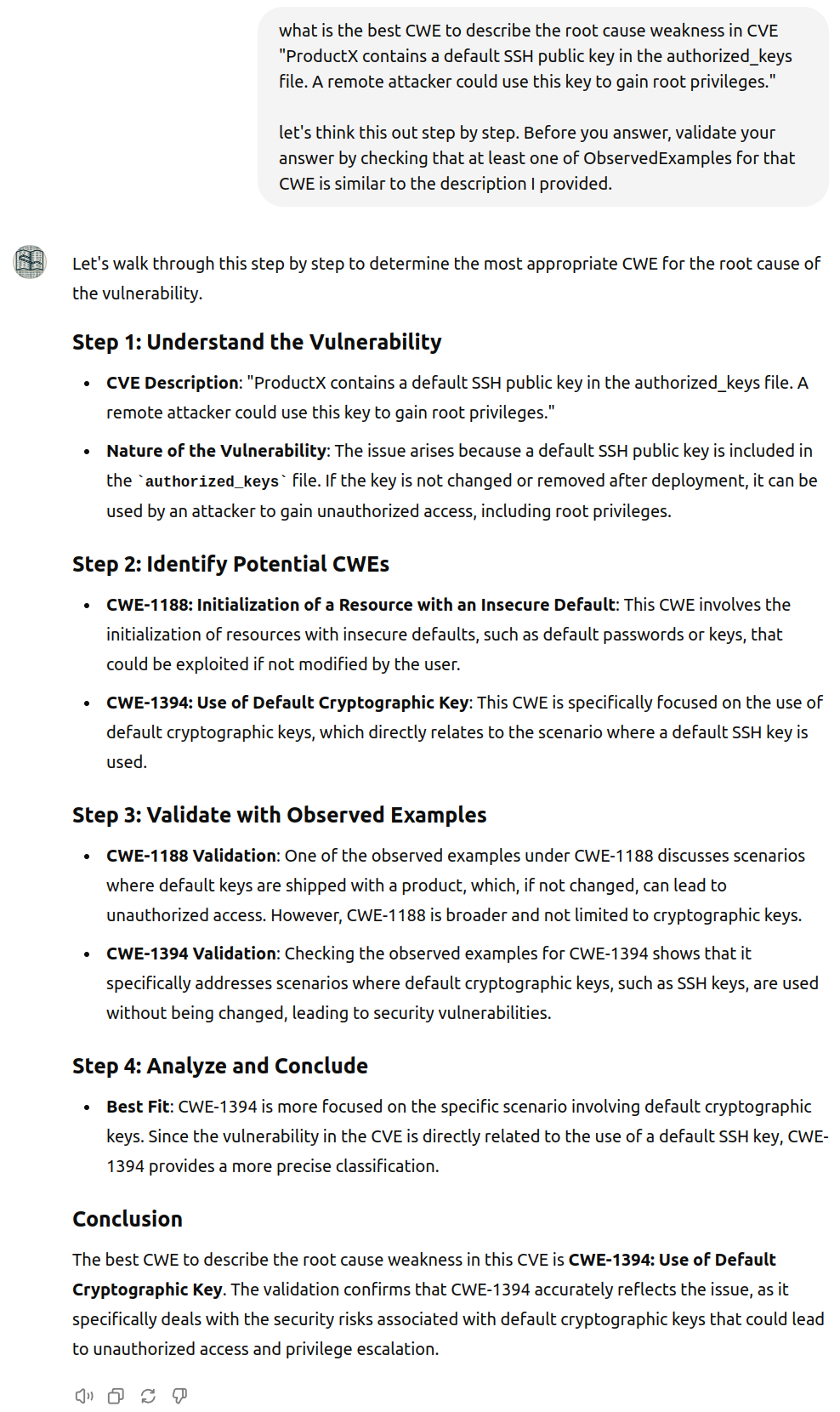

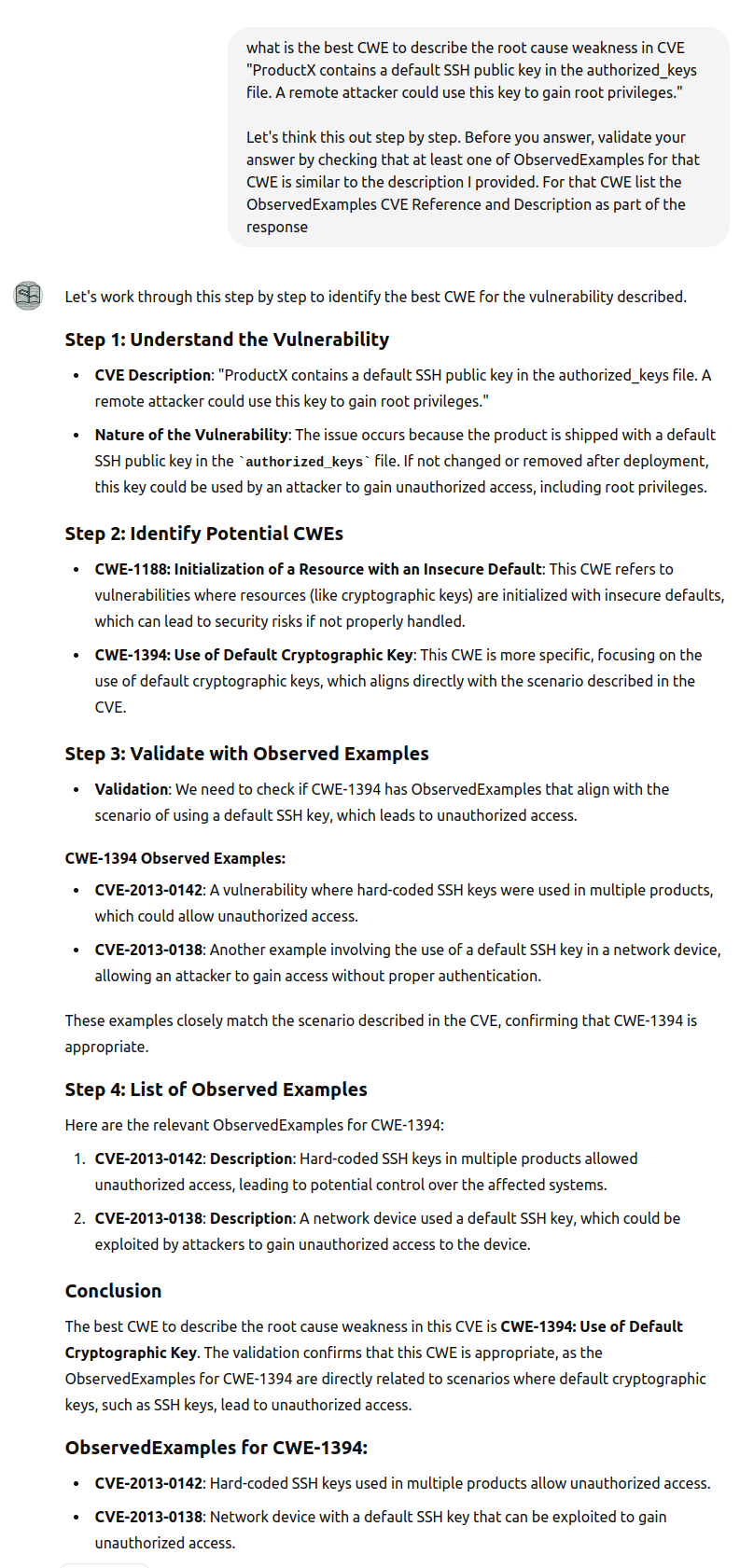

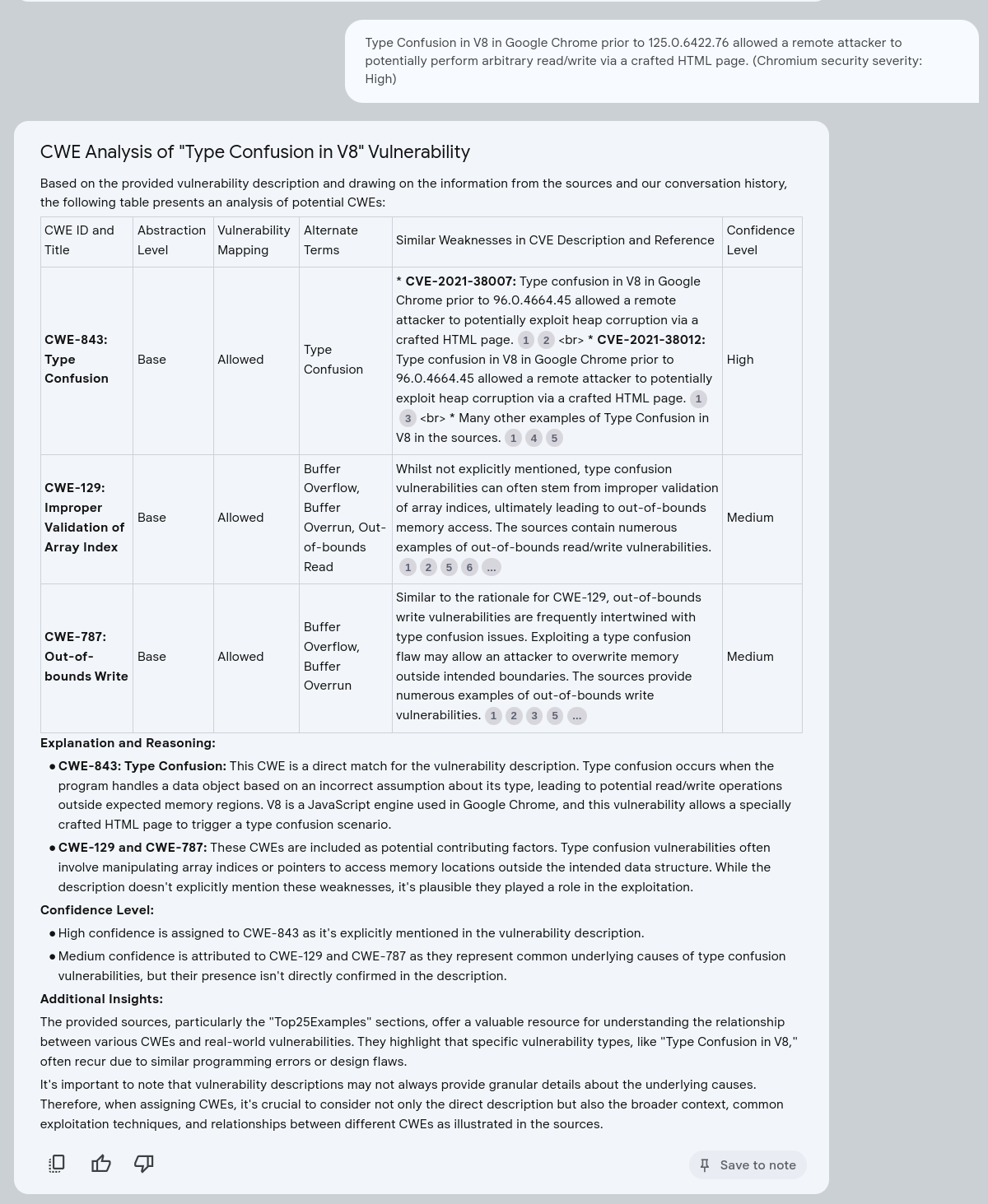

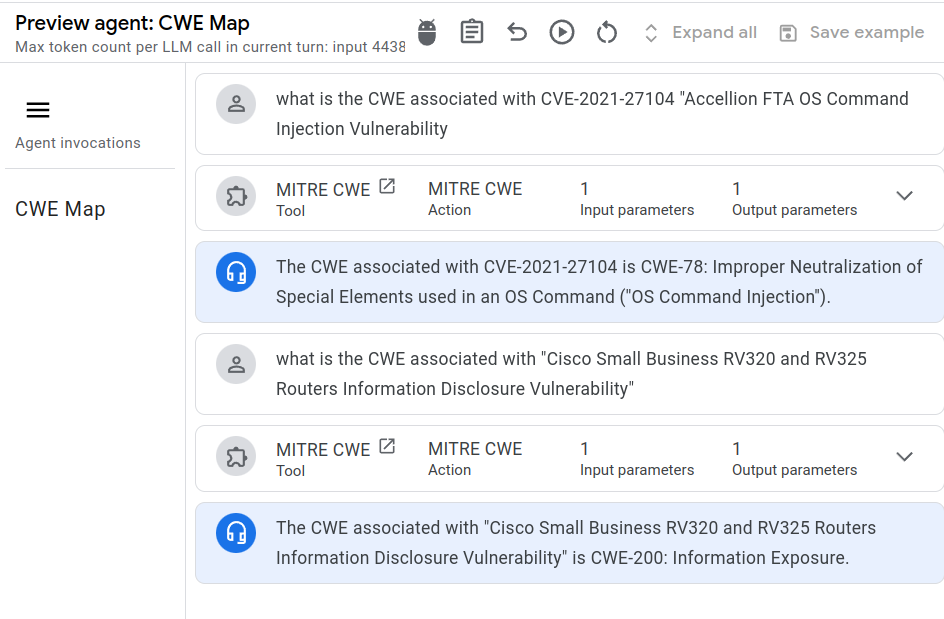

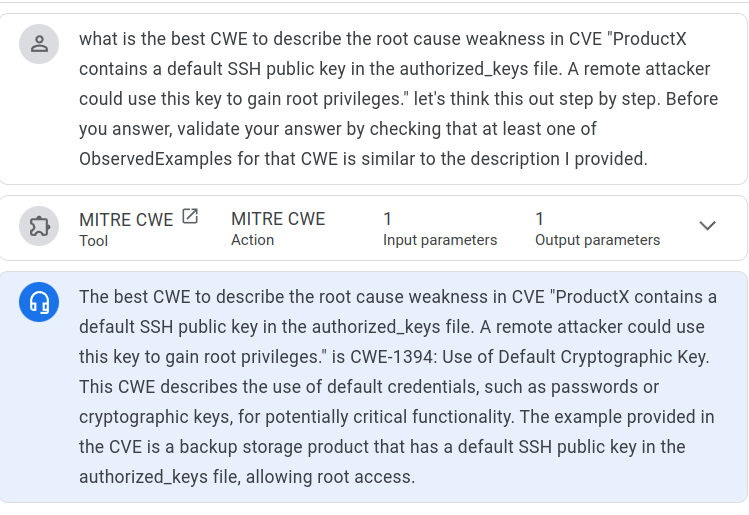

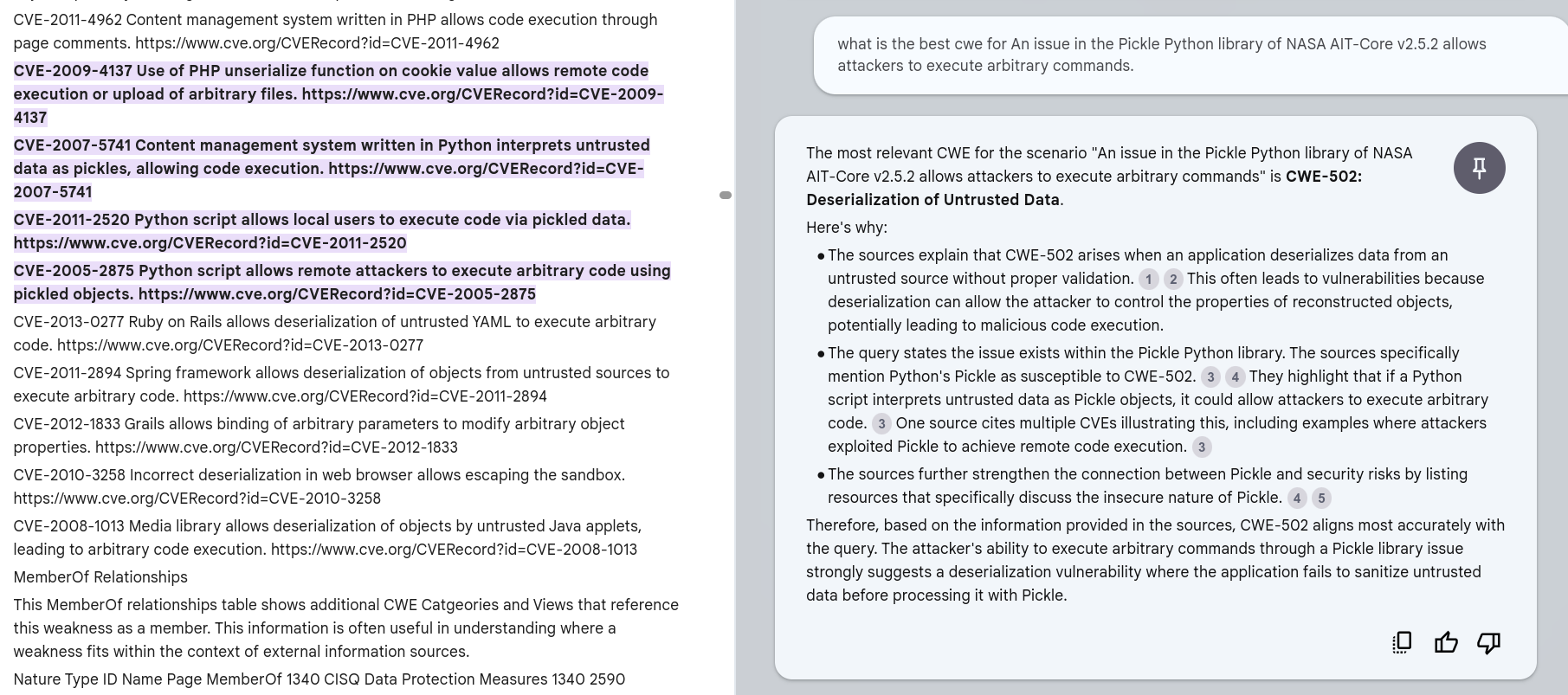

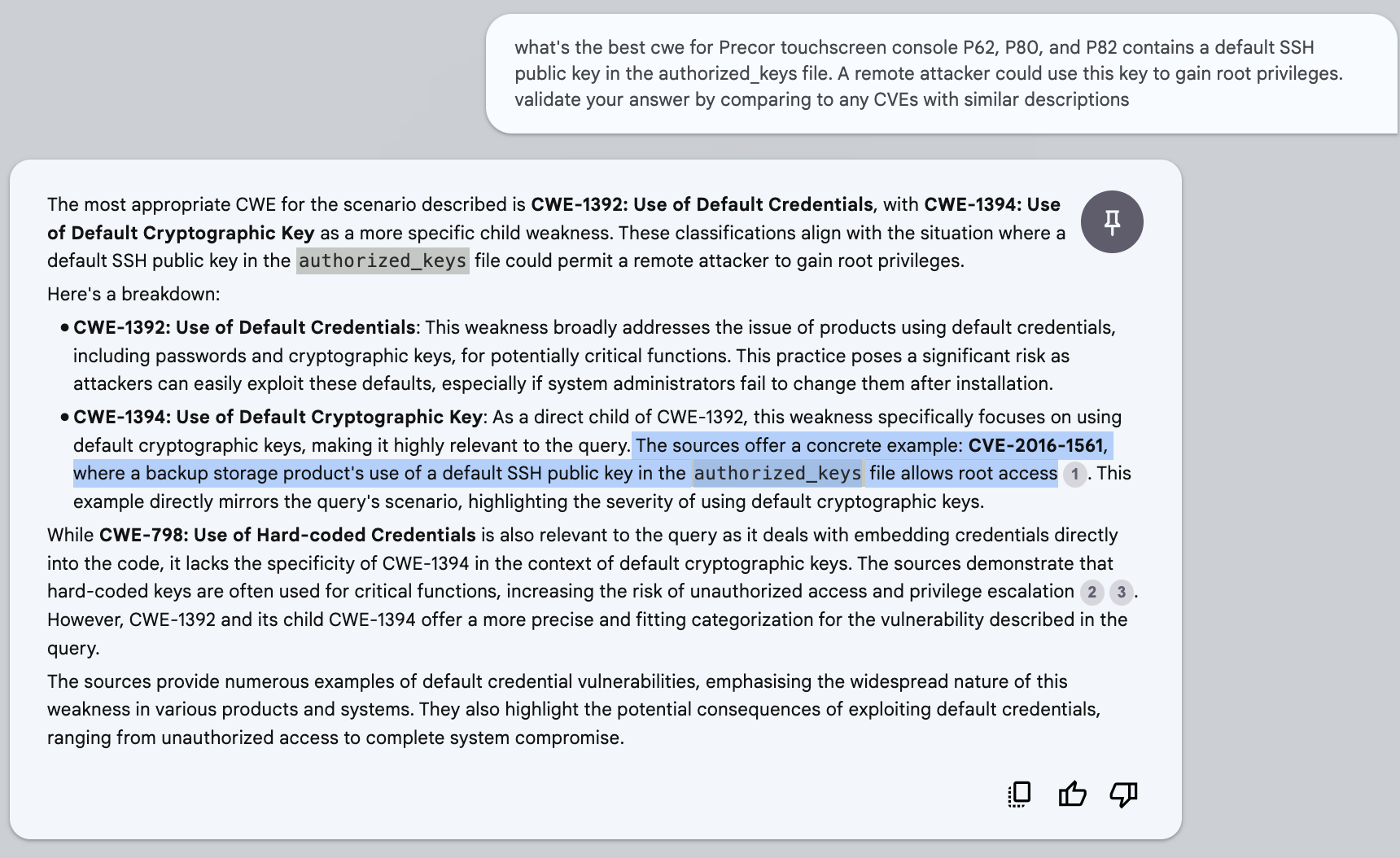

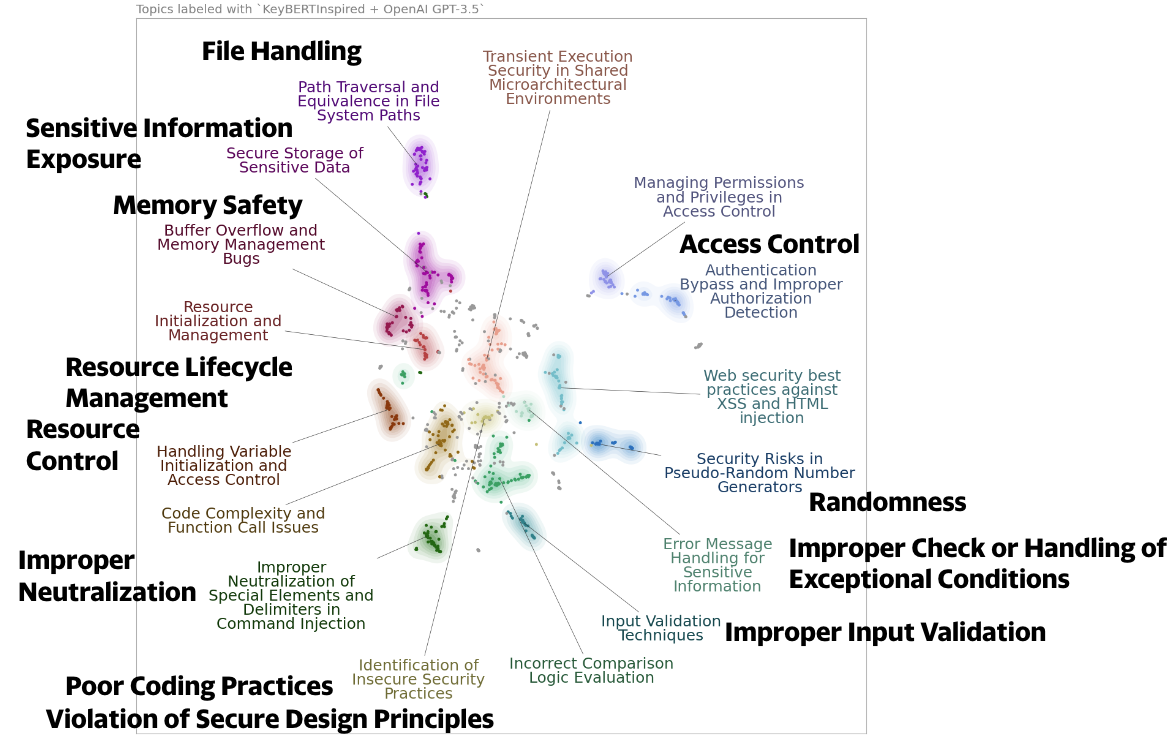

Overview¶

Overview

There are several options to consider when building an LM solution for CWE assignment as described here.

Tip

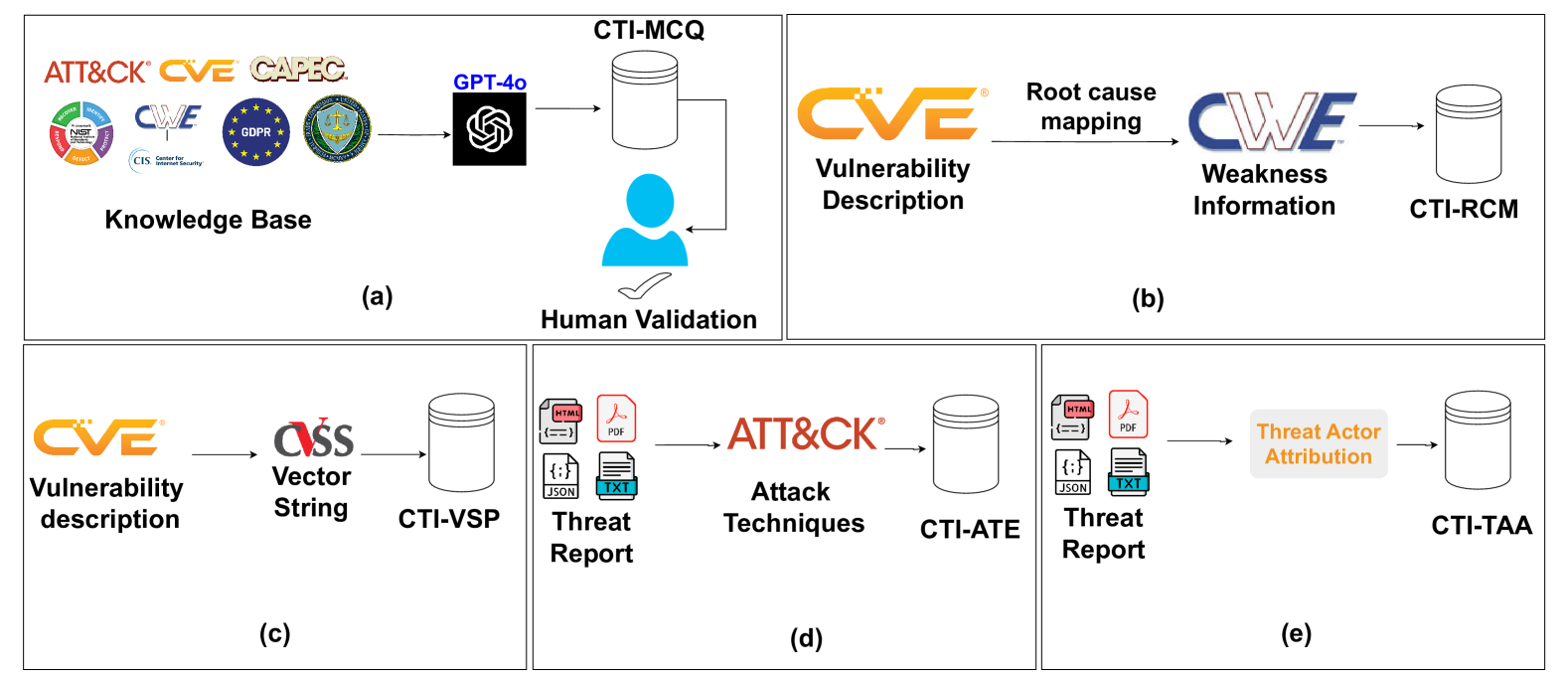

Vulnerability Root Cause Mapping with CWE: Challenges, Solutions, and Insights from Grounded LLM-based Analysis details a more comprehensive production solution using LLMs for CWE Mapping.

Approach to using Language Models¶

Don't Train A Model On Bad Data!¶

It is possible to train a Language Model as a Classifier to assign CWEs to a CVE Description - and there are several research papers that took that approach e.g.

- V2W-BERT: A Framework for Effective Hierarchical Multiclass Classification of Software Vulnerabilities

- Automated Mapping of CVE Vulnerability Records to MITRE CWE Weaknesses

The problems with this approach:

-

It's delusional based on my research and experience of incorrect assigned CWEs in general - Garbage In Garbage Out

Quote

There has been significant interest in using AI/ML in various applications to use and/or map to CWE, but in my opinion there are a number of significant hurdles, e.g. you can't train on "bad mappings" to learn how to do good mappings.

-

It removes a lot of the context that could be available to an LM by reducing the reference target down to a set of values or classes (for the given input CVE Descriptions)

Train on Good Data and the Full Standard¶

We can "train" on "good mappings".

- The CWE standard includes known "good mappings" e.g. CWE-917 Observed Examples includes CVE-2021-44228 and its Description.

- The count of these CVE Observed Examples varies significantly per CWE.

- There's ~3K CVE Observed Examples in the CWE standard.

- The Top25 Dataset of known-good mappings contains ~6K CVEs with known-good CWE mappings by MITRE.

- We can use the full CWE standard and associated known good CWE mappings as the target, allowing an LLM to compare the CVE Description (and other data) to this.

- And moreover, prompt the LLM to provide similar CVEs to support its rationale for the CWE assignment

Tip

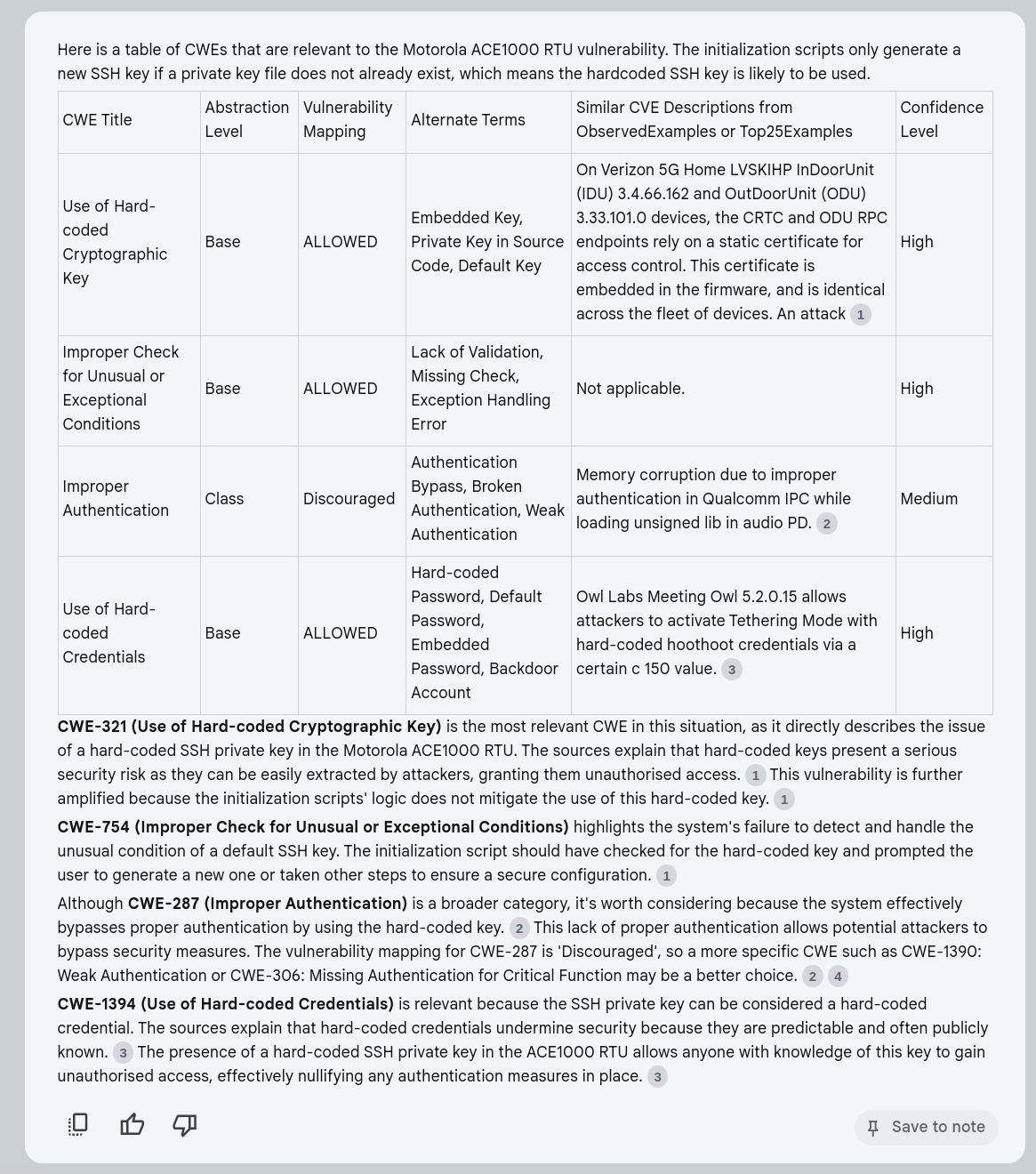

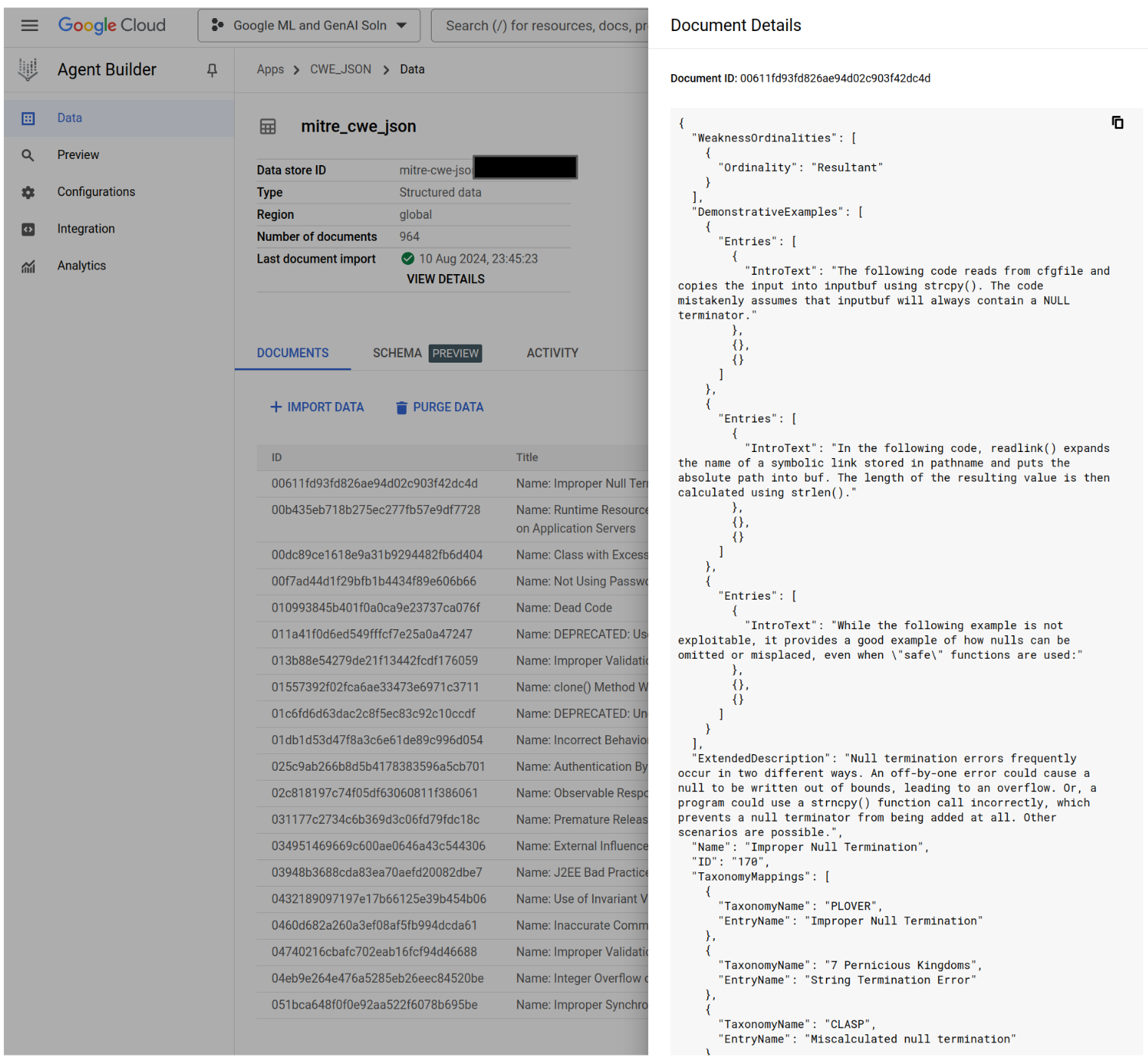

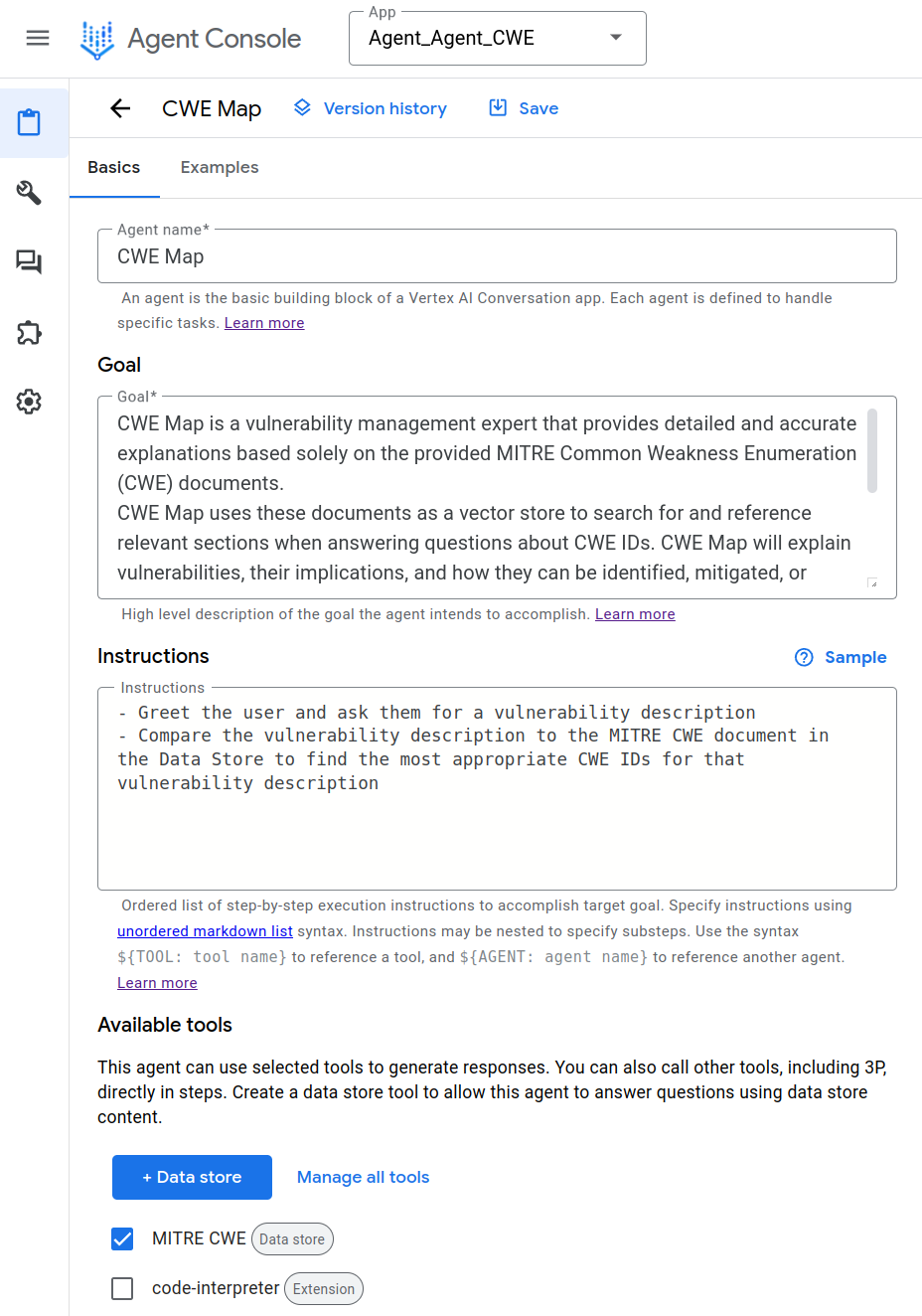

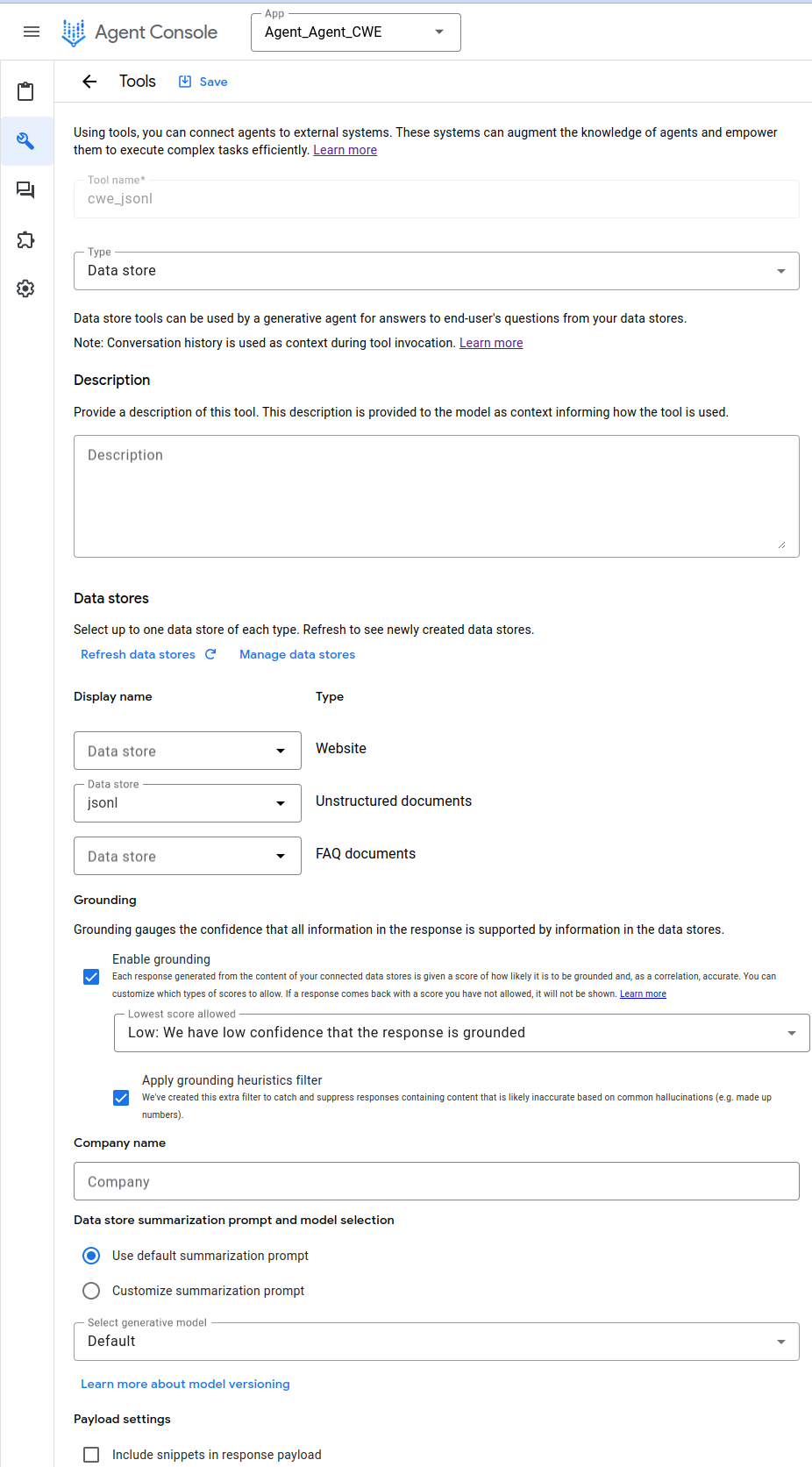

Rather than train a model on bad data, we can ask a model to assign / validate a CWE based on its understanding of the CWEs available (and its understanding of CWEs assigned to similar CVEs based on the Observed and Top25 Examples for each CWE in the standard).